Comprehensive neuromuscular assessment of chronic pelvic pain (including BPS/IC)

1 Department of Urology, University Hospital Antwerp and University Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

Abstract

Patients diagnosed with chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) consult with a variety of symptoms related to organs in the pelvic region, in the absence of a proven infection, pathology or confusable disease. The ESSIC classification of bladder pain syndrome (BPS) according to the results of cystoscopy and of biopsy has to be used for the differentiation between BPS subtypes. A systematic approach is needed trying to understand the problem in CPPS. A four step plan with attention for emotional factors is indicated to assess these patients. A thorough clinical investigation includes a physical assessment as well. Assessing CPPS patients shows musculoskeletal pain that is not restricted to the pelvis. The whole spine can be painful. Manual applied neurodynamic tests and local palpation show mechanosensitivity of the pudendal nerve in most of cases, although almost all other nerves of the lumbosacral plexus can have minor nerve injuries. One patient can have multiple mononeuropathies simultaneously. A thorough physical assessment can indicate the anatomical origins of pain and help to determine the therapeutic approach. The variety of symptoms suggesting simultaneous organ dysfunction in multiple systems, indicate the need for a multidisciplinary approach.

Abbreviations

AIGS: Abnormal impulse generated site

CPP: Chronic pelvic pain

CPPS: Chronic pelvic pain syndrome

CRPS: Complex regional pain syndrome

ESSIC: International Society for the Study of BPS

IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome

ICSI: Interstitial cystitis symptom index

LUT: Lower urinary tract

NIH-CPSI: National Institutes of Health – chronic prostatitis index

PD-Q: PainDETECT questionnaire

PUF: Pain and urgency, frequency questionnaire

QoL: Quality of life

S-LANSS: Self-completed Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs

Introduction

Chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) is characterized by persistent genitourinary pain, associated with symptoms perceived to be related to organs in the pelvic region, in the absence of a proven infection or other identifiable pathology (e.g. lower urinary tract (LUT), sexual, bowel, pelvic floor or gynaecological) [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. CPPS has an important negative impact on the quality of life [6]. The complexity and interactive aspects of the CPPS and its multidisciplinary management underlines the need for a detailed diagnosis. To discriminate the different syndromes within CPPS remains a challenge because the overlap of symptoms of different systems. The pain is mostly perceived in different structures related to the pelvis and poorly localized. From the history, investigations and physical assessment the syndrome can be determined. Painful areas and pain points have to be convincingly reproduced by local palpation [7]. The CPPS are described in Table 1.

| Chronic pelvic pain syndromes (CPPS) | |

| Urological pain syndromes |

|

| Bladder pain syndrome (BPS)* | pain in the urinary bladder region, accompanied by at least one other symptom:

|

| Urethral pain syndrome | pain perceived in the urethra |

| Penile pain syndrome | pain within the penis that is not primarily in the urethra |

| Prostate pain syndrome | pain which is convincingly reproduced by prostate palpation |

| Scrotal pain syndrome | pain localized within the organs of the scrotum; generic term when the site of the pain is not clearly testicular or epididymal |

| Testicular pain syndrome | pain perceived in the testes |

| Post-vasectomy pain syndrome | scrotal pain syndrome that follows vasectomy |

| Epididymal pain syndrome | pain perceived in the epididymis |

| Gynaecological pain syndromes | |

| Vulvar pain syndrome | vulvar pain (according ISSVD: vulvodynia is vulvar pain that is not accounted for by any physical findings) |

| Generalized vulvar pain syndrome | pain/burning cannot be consistently and precisely localised by point-pressure mapping |

| Localized vulvar pain syndrome | pain that can be consistently and precisely localised by point-pressure mapping to one or more portions of the vulva |

| Vestibular pain syndrome | pain that can be localised by point-pressure mapping to the vestibule or is well perceived in the area of the vestibule |

| Clitoral pain syndrome | pain that can be localised by point-pressure mapping to the clitoris or is well perceived in the area of the clitoris |

| Endometriosis-associated pain syndrome | pain with laparoscopicly confirmed endometriosis, when the symptoms persist despite adequate endometriosis treatment |

| CPPS with cyclical exacerbations | non-gynaecological organ pain that frequently shows cyclical exacerbations (e.g., IBS or BPS) and differs from dysmenorrhoea, in which pain is only present with menstruation |

| Dysmenorrhoea | pain with menstruation |

| Musculoskeletal system | |

| Pelvic floor muscle pain syndrome | pelvic floor pain that may be associated with overactivity of or trigger points within the pelvic floor muscles or trigger points found in muscles, such as the abdominal, thigh and paraspinal muscles and even those not directly related to the pelvis |

| Coccyx pain syndrome | pain perceived in the region of the coccyx |

| Gastrointestinal pelvic pain syndromes | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) | pain perceived in the bowel, according to the Rome III criteria |

| Chronic anal pain syndrome | pain perceived in the anus |

| Intermittent chronic anal pain syndrome | pain unrelated to the need to or the process of defecation, that seems to arise in the rectum or anal canal |

| Pudendal pain syndrome | |

| * ESSIC proposal (adapted from [2]) |

|

One specific form of CPPS is interstitial cystitis/ bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) [8]. It presents with perceived bladder pain ranging from mild discomfort to severe disability, and a variety of urinary symptoms. ESSIC defined BPS as pain in the urinary bladder region, accompanied by at least one other symptom (pain worsening with bladder filling; day-time and/or night-time urinary frequency). In IC/BPS the lower urinary tract symptoms may be accompanied with symptoms in other systems (e.g. bowel, sexual, pelvic floor, gynaecological or musculoskeletal). To classify the types of bladder pain syndrome, ESSIC determined a classification system according to the results of cystoscopy with hydrodistension and of biopsy [9]. The differentiation between bladder pain syndrome (BPS) subtypes (e.g. type 3C BPS and non-type 3C BPS) using questionnaires remains unclear [10]. Table 2 shows the ESSIC classification system for bladder pain syndrome.

| ESSIC classification of types of BPS | ||||

| Cystoscopy with hydrodistention | ||||

| Biopsy | Not done | Normal | Glomerulationsa | Hunner’s lesionb |

| Not done | XX | 1X | 2X | 3X |

| Normal | XA | 1A | 2A | 3A |

| Inconclusive | XB | 1B | 2B | 3B |

| Positivec | XC | 1C | 2C | 3C |

|

a Cystoscopy: glomerulations grade 2–3. |

||||

CPPS must be distinguished from forms of chronic pelvic pain that have well-defined causes such as infection, endometriosis, haemorrhoids, anal fissure, pudendal neuropathy, sacral spinal cord pathology, vascular and cutaneous disease, psychiatric conditions) [2], [11].

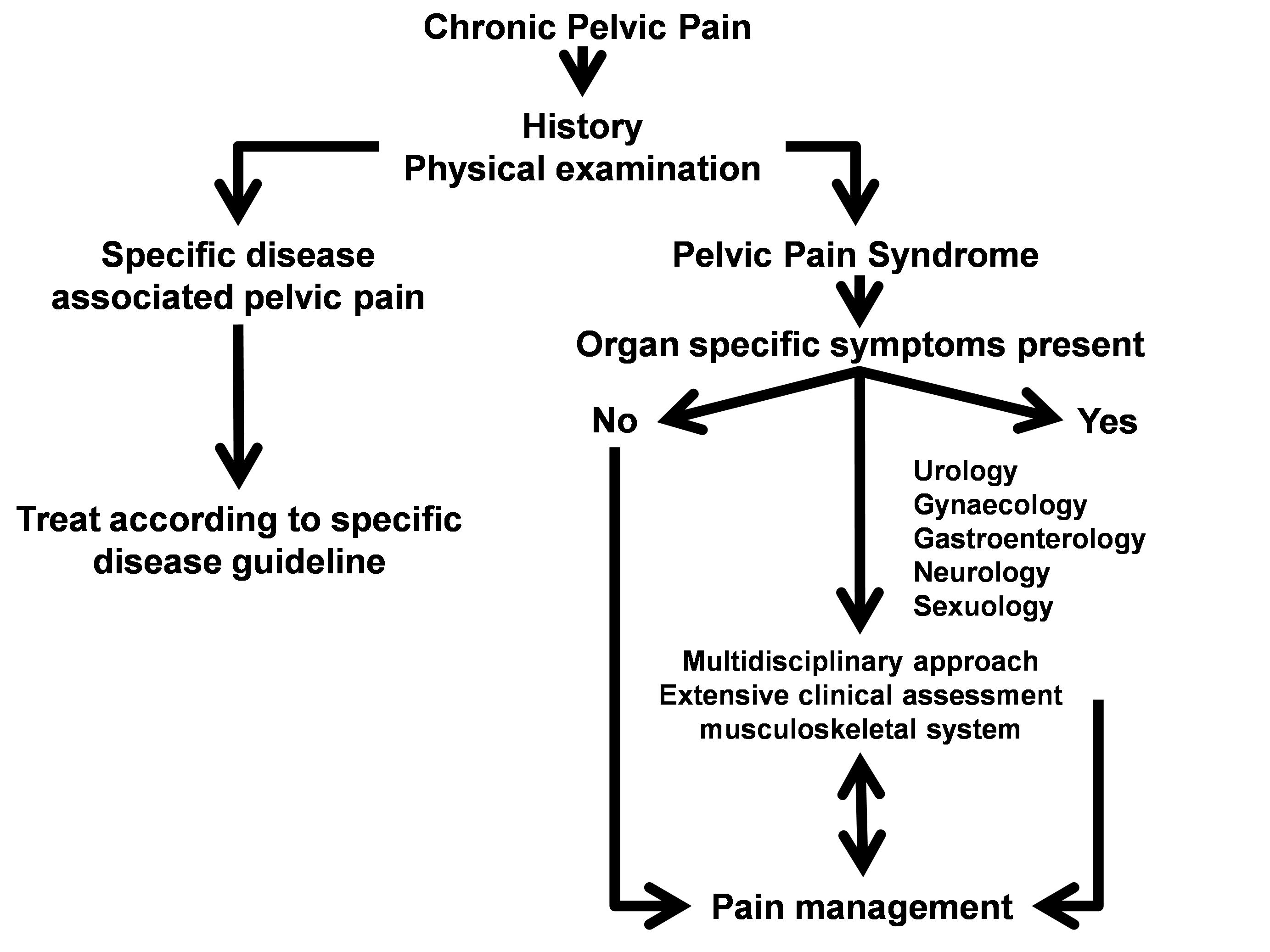

Diagnosis and managing CPP

Specific disease associated pelvic pain needs an appropriate treatment according to the designated disease guideline. In CPPS, the variety of symptoms suggesting simultaneous organ dysfunction in multiple systems, indicate the need for a multidisciplinary approach. Figure 1 shows the algorithm for diagnosis and management of CPP.

Figure 1: Algorithm for diagnosis and management of CPP [3]

(adapted from [2])

To determine which of the different syndromes is present remains a challenge because of the overlapping symptoms and the interrelations of structures in the pelvic region. History, examination and investigations may suggest the pain as being generated from a specified anatomical pelvic area (e.g. BPS, PPS, pudendal nerve pain syndrome). On the other hand, visceral pain, can refer to a cutaneous site, and be accompanied by muscular hyper tonicity [12], [13], emotional and autonomic responses [14], [15]. The common innervation of the pelvic organs and cross sensitization can partially explain the functional interference between systems [16], [17]. Complicating matters further, pain mechanisms such as central sensitization and chronic regional pain syndrome are important chronic pain states frequently identified in the BPS patient [18].

Given the complexity of pain generation in the patient presenting with chronic pelvic pain, a systematic approach for evaluation is strongly recommended through a ‘four-step protocol’ [6], [19], [20]. A systematic approach to determine pain mechanisms (e.g. referred pain, local inflammation, central/peripheral sensitisation), and the anatomical painful areas aims at obtaining supplementary information to refine the therapeutic management before jumping into various treatment attempts [3].

A thorough clinical assessment: the four-step plan

The complexity and interactive aspects of the CPPS implies the eventual need for multidisciplinary management. Once the diagnosis CPPS has been confirmed, a further clinical assessment can help to chose the best therapeutic approaches. A thorough clinical assessment is described here, based on the four-step protocol for investigation of CPPS. The thorough clinical assessment aims at acquiring a maximum of diagnostic information. A thorough clinical assessment takes about 30 minutes, and can easily be done by a well trained physical therapist or osteopath. Table 3 shows the four steps to undertake for obtaining essential information.

| 4-step plan | |

| Step I | History with questioning for complaints in other systems |

| Step II | Evaluation of previous assessments and reports |

| Step III |

Thorough clinical assessment

|

| Step IV |

Extensive clinical assessment of the musculoskeletal system

|

Step I: history with questioning for complaints in other systems

History taking will often develop a list of symptoms which are related to different pelvic structures. In IC/BPS a voiding log for frequency, urgency, and nocturia is needed. Bowel habits must be investigated. Sexual complaints and impact of the symptoms on QoL must be evaluated. One should ask for description of the pain (e.g. area, onset, presentation, burning feeling related to urination), and interfering factors of complaints. The pain description has to be scrutinized in detail (e.g. episodic versus constant, single versus several locations, time relation to voiding, defecation, sexual activities, and bother). Attention for psychological, behavioural, and social problems is needed taking a history [21], [22], [23]. The social history and economic burden as a result of the illness should not be underestimated.

| Symptoms in CPPS | |

|

Urological system

|

|

|

Gynaecological system

|

|

|

Musculoskeletal system

|

|

|

Gastrointestinal system

|

|

|

Pudendal pain

|

Questionnaires can be useful for evaluation of symptoms (e.g. McGill [24], Pollard [25], [26], [27], NIH-CPSI [28], [29], [30], [31], ICSI [32], PUF [33], [34], [35] questionnaires). Because of their specific properties, they do not give the same kind of information and the results must be interpreted separately for each patient [36]. The PainDETECT questionnaire (PD-Q) and the self-completed Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (S-LANSS) can help to give additional information about neuropathic pain in BPS [37], [38], [39], [40]. It has been shown that neuropathic pain screening questionnaires have limited measurement properties. They do not replace a thorough clinical assessment [41]. The University of Wisconsin IC scale and the Genitourinary Pain Index (GUPI) can be used to indicate the severity of symptoms in BPS [42], [43], [44], [45].

Questionnaires for evaluation of mental distress, coping with pain and catastrophizing symptoms (e.g. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), Chronic Pain Coping Inventory (CPCI), Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)) can be used for the evaluation of the emotional impact on pain and symptoms, as a result of BPS [37], [46], [47], [48], [49].

Step II: evaluation of previous assessments and reports

Information from previous technical and specialist assessments need to be taken in account, including all radiographic examinations as RX, NMR, CT and lab data [50]. These previous reports can indicate the presence of confusable diseases [9]. This time-consuming initial effort is a needed investment to avoid fragmented, multiple visits with poor results during many years.

Step III: thorough clinical assessment

This includes a clinical neurologic assessment, palpation of the external sexual organs, and a palpation by rectal/vaginal ways.

Clinical neurologic assessment

The clinical neurologic assessment includes an examination of the lumbosacral plexus evaluating motor, sensory function, and reflexes [51].

With an EMG, the clinical signs can be confirmed. In absence of EMG findings, pain of neuropathic origin is not excluded. Neuropathic pain can present without evidence for nerve injury (e.g. EMG) [52], [53], [54]. An EMG is needed when a nerve injury is expected and before neurodynamic testing and treatment, when clinical signs exist. A minor neuropathy or minor nerve injury is a peripheral mononeuropathy in which EMG does not indicate a malfunction, but in which the normal physiology of the nerve is disturbed.

Peripheral nerve entrapments and minor nerve injuries

Entrapment neuropathies share a common pathophysiology: localized ischemia, endoneurial edema, and vascular impairment from ongoing mechanical pressure or longitudinal stress on a nerve [54], [55]. Peripheral nerve entrapment (e.g. mononeuropathy), compression, or irritation of nerve roots forming the lumbosacral plexus may cause neuropathic pain and sustain sensitization [56]. In early nerve compression the symptoms are caused by vascular impairment, and initial changes occur at the blood-nerve barrier. There is no lymphatic drainage of the endoneurial space [55] making it susceptible for inflammation. Mononeuropathy can be an indication of a disturbed homeostatic endoneurial microenvironment which gives an indication for mechanosensitivity treatment.

The viscoelastic properties of nerve tissue may accommodate for a modest increase in length. Normal physical stresses upon a nerve during limb movement may be sufficient to provoke mechanosensitivity, suggesting peripheral sensitization. Peripheral nerve sensitization can be present even in absence of altered EMG [53], [54]. The neurologic assessment can be completed with manual neurodynamic testing indicating movement restrictions and mechanosensitivity of the peripheral nerves of the lumbosacral plexus [3]. Neurodynamic tests showing mechanosensitivity of peripheral nerves, indicate the need for specific mobilisation of the nervous system [57], [58], [59].

Neurodynamic testing

Neurodynamic tests are manual applied techniques to assess the mobility of peripheral nerves. Nervous structures such as nerves and the spinal cord must be able to move freely during movement of the limbs and spine. Decreased ability to move will result in circulatory disturbances inside a nervous structure and pain mediators will install. Neurodynamic tests and neurodynamic treatment are contra indicated when a nerve injury (e.g. neuropraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis) or polyneuropathy is confirmed. Neurodynamic tests can show mechanosensitivity indicating a mononeuropathy suggesting entrapment of a nerve [3].

Neurodynamic techniques

Applying a moderate stress by increasing the length of the nerve by limb movement (tensioning), or gentle local palpation of a nerve itself, can show the existence of mechanosensitivity indicating a minor neuropathy [60], [61]. Mechanosensitivity in peripheral nerves may occur in almost all peripheral nerves of the lumbosacral plexus and can be assessed and treated with a neurodynamic approach restoring the circulation within the nerve with gliding and tensioning techniques [57], [58], [59]. Gliding means the ability of a nerve to move aside to the surrounding nerve bed during limb movement, and is also termed ‘displacement’ [54]. This approach was also described for upper limb peripheral mechanosensitivity testing [62]. Neurodynamic testing also includes manually applied moderate stress testing by increasing the length of the nerve by limb movement (tensioning). Neurodynamic tension testing or local palpation can show the existence of minor neuropathies [57], [58]. Local applied gentle palpation of the nerve itself can show peripheral mechanosensitivity as well. Neurodynamic assessment can show minor neuropathies and is important when treating chronic pain [60], [61]. The neurodynamic tests of the lumbosacral plexus can indicate mechanosensitivity and be considered as an abnormal impulse generated site (AIGS) or ectopic activity, maintaining sensitization [63]. Central sensitization can be maintained by permanent peripheral sensory neuroinflammation [64]. Applying a brush and pointed stimuli to the painful area can show allodynia or hyperalgesia.

Mechanosensitivity in the lumbosacral plexus, can be confirmed by local palpation or by using neurogenic tension tests at the level of the sciatic, iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, obturator, lateral cutaneous femoral, perineal, dorsal, and the medial, lateral and inferior cluneal nerves. Increase of pain during “straight leg raise” can possibly point out neuropathic pain of the sciatic nerve. If lying on the back provokes pain due to hip extension combined with internal rotation at the level of the groin or genital organs this can suggest a minor neuropathic problem at the level of the ilioinguinal n. (L1) or genitofemoral n. (L1–L2). Ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerve mechanosensitivity can be shown by palpating the internal and external inguinal annular ring. When an increase of pain occurs during hip extension with adduction, a minor neuropathy of the lateral cutaneous femoral n. (L2–L3) can be pointed out. Increase of pain in the adductor region, with hip abduction can indicate a minor neuropathy at the level of the obturator n. (L2–L3–L4).

The pudendal pain syndrome should be considered as increased mechanosensitivity of the pudendal nerve. Instead, pudendal neuropathy has been defined as a specific disease or pathology (nerve injury) with pain as a result and is not an indication for neurodynamic treatment [65]. Extensive neurodynamic testing aspects and palpation procedures of the lumbosacral plexus peripheral nerves are described in Table 5.

| nerve(s) | root | pain area | neurodynamic test | palpation | |

| area | approach | ||||

| iliohypogastric | L1 | hypogastric- & lat. gluteal | hip ext. & endorot. | hypogastric | EA, BM, VA |

| ilioinguinal | L1 | inguinal | hip ext. & endorot. | inguinal ring, spermatic cord, scrotal | EA, BM, VA |

| genitofemoral | L1–L2 | sup. 1/3th ant. femoral, inguinal, scrotal, vulvar | hip ext. & endorot. | inguinal ring, spermatic cord, scrotal | EA, BM, VA |

| lat. fem. cut. | L2–L3 | lat. aspect of the thigh | hip ext. & add. | med. ASIS | EA |

| obturator | L2–L4 | lower med. aspect of the thigh, above the knee | hip abd. | obturator foramen | RA |

| femoral | L2–L4 | ant.- med. aspect of the thigh | hip ext. | inguinal, lat. femoral artery (hip ext.) | EA |

| saphenous | L2–L4 | ant.- med. aspect of the leg & infrapatellar | hip ext. & plantar flex., ev. ankle | med.-inf. patella, ant. of med. malleolus | EA |

| sciatic | L4–S3 | gluteal, post. aspect leg & lat. foot | hip flex., add., endorot. & ev./inv. ankle | 1/2 between major trochanter & coccyx | EA |

| post. fem. cut. | S1–S3 | post. aspect of the thigh | hip flex., add., endorot. | med. post. aspect of the thigh | EA |

| tibial | L4–S3 | med. malleolus, plantar, calcaneal | hip flex. add., endorot. & dorsal flex./ev. ankle | 1/2 popliteal fossa | EA |

| sural (tibial) | S1–S2 | post.- lat. aspect of the calf, lat. aspect of foot | hip flex. add., endorot. & dorsal flex./ev. ankle | post. lat. malleolus | EA |

| peroneal (com) | L4–S2 | 1/4th sup. ant.-post. aspect of lower extremity | hip flex. add., endorot. & dorsal flex./ev. ankle | post. aspect of sup. head of fibula | EA |

| peroneal (super) | L4–S2 | post.- lat. aspect lower extremity & dorsum foot | hip flex. add., endorot. & dorsal flex./ev. ankle | foot dorsum | EA |

| peroneal (deep) | L4–S2 | lower extremity & triangle between 1st & 2nd toe | local palpation is indicated | triangle between 1st & 2nd toe | EA |

| pudendal* | S2–S4 | perineal floor | local palpation is indicated | pudendal canal | RA |

| perineal* | S2–S4 | perineal floor | local palpation is indicated | perineal floor | EA |

| dorsal* | S2–S4 | dorsal aspect penis, clitoris | local palpation is indicated | dorsal aspect penis | EA |

| lat. cluneal | L1–L3 | post. aspect of iliac crest | heterolat. side bending spine, hip flex./endo | post.-lat. aspect of iliac crest | EA |

| med. cluneal | S1–S3 | post. - inf. sacral area | heterolat. side bending spine, hip flex./endo | post.-med. aspect of sacrum | EA |

| inf. cluneal | S1–S3 | sciatic tuberosity | local palpation is indicated | inf.-lat. sciatic tuberosity | EA |

| * must be evaluated by palpation; ev.: eversion; inv.: inversion; ASIS: anterior superior iliac spine; BM: bimanual palpation; EA: external assessment; VA: vaginal assessment; RA: rectal assessment | |||||

A study [66] showed at least one neuropathy in 88% of CPPS patients (n=26), while 42% had multiple neuropathies [67]. One patient had mechanosensitivity in 12 nerves or nerve branches. In 12% no mechanosensitivity, could be shown. Compared to other nerves of the lumbosacral plexus with mechanosensitivity, mainly the pudendal nerve (85%) was painful during palpation of Alcock’s channel. Femoral, sciatic, sural, peroneal, and tibial neuropathies were shown as well in 4%.

Electrodiagnostic evaluation of the sensory function

Electrodiagnostic evaluation of the sensory function determining current perception thresholds can be an aid, evaluating neuropathy and afferent nerve activity from the LUT [19], [68]. This evaluation method has been suggested for pain assessment in research and clinic. Studies trying to assess sensory function in a semi objective way resulted in a wide variability of current perception thresholds (CPTs) in healthy volunteers and a weak agreement between normative data of control groups [69], [70].

Neurodynamic tests to investigate increased mechanosensitivity demonstrated a moderate reliability [62]. Therefore we can conclude that neurodynamic testing in CPPS is important.

Clinical assessment for hernias

Abdominal, inguinal or femoral hernias sometimes manifest themselves with CPP, groin pain or pain at the gender organs. We can distinguish inguinal and femoral hernias by palpation and where pain is provoked. Also a hernia at the level of the external or internal inguinal ring can often be found by palpation. With palpatory provoked pain of the abdominal wall, hernias at the level of the Spighelian line and umbilical hernias must be excluded [71]. A hernia in some cases can be diagnosed by palpation and /or by using the valsalva-manoeuvre standing and also in standing position with light flexion of the trunk. Ultrasound evaluation can confirm. Some hernias only manifest themselves with the Valsalva manoeuvre with the trunk in an anterior position and are missed during ultrasound, because this examination is usually conducted with the patient lying on the back. The Carnet’s sign (increased pain with tensing abdomen) can indicate abdominal wall pain [72].

Palpation of external genitalia

Observe the extern gender organs for rash, secretion, abscess formation, perineal fistula, atrophic disorders or signs of trauma. In male patients also palpate the testis, epididymis, the spermatic cord and the penis. Is there a scrotal mass? In women the palpation of the labia, vestibular glands and the urethra must be included and localized genital pain points must be differentiated from generalized vulvar pain. Q-Tip testing can show the pain area.

Palpation of the pelvic floor (rectal/vaginal assessment)

The pelvic floor function must be evaluated distinguishing the function of the urogenital diaphragm, the levator muscle and the anal sphincter. A score of power, endurance and exhaustion is noted (Oxford scale) [73], [74]. When on demand relaxation is a problem, voiding or defecation problems are suspected, indicating the need for uroflow and further bowel assessment. A study showed palpatory provoked pain in at least one part of the pelvic floor in men and women with CPPS. The pelvic floor scores were not weak in general [67].

With palpation the pain can be differentiated at the level of the pudendal canal or the area of the obturator foramen. The sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments can be sensitive, indicating ligamentary stress or neuropathic pain of perforating cutaneous branches. Coccygeal pain must be determined and may be accompanied by pelvic floor hypertonia. Pain can be differentiated by using palpation at the different parts of the pelvic floor and indicated pain points. Sacrococcygeal joint instability must be excluded and can be confirmed with X-ray of the patient in a standing and sitting position [75].

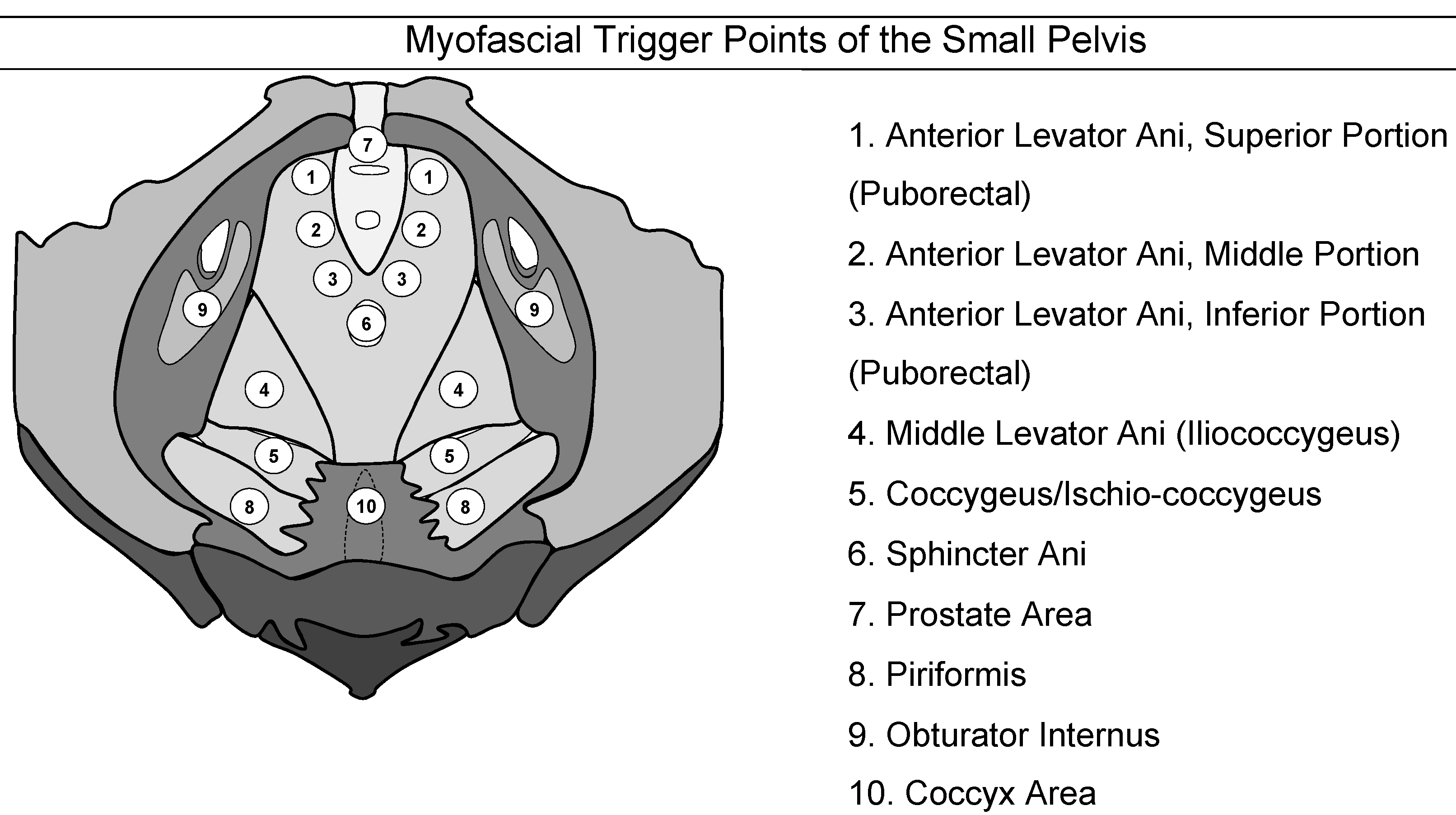

Myofascial trigger points have been defined as hyperirritable spots in a skeletal muscle that are associated with a hypersensitive palpable nodule in a taut band [76]. The spot is tender when pressed and can give rise to characteristic referred pain [77]. Figure 2 shows the myofascial pain points as described by Anderson et al. [78].

Figure 2: Myofascial trigger points of the pelvis

(adapted from the “Stanford Protocol” [79])

Step IV: extensive clinical assessment of the musculoskeletal system

The clinical assessment of the musculoskeletal system in patients with CPP can be excelled in different postures and is not restricted to the pelvis. Next to the posture, movement limitations need to be confirmed at the level of the complete spine and pelvis. Observe the posture in standing, lying and sitting position. Let the patient indicate the area of the pain [80], [81]. Spinal mobility is assessed with palpation, and active and passive movements. Asymmetry in the amplitude is noted, with attention to a unilateral shorter lower limb or scoliosis. The joint play of the sacroiliac joints, the pubis and the sacrococcygeal joints must be assessed. The greater trochanter and the ischial tuberosity must be palpated to indicate ischial or trochanteric bursitis. In the buttock area a minor neuropathy of the inferior cluneal nerve, tendonitis must be differentiated. Osteogenic pain can indicate periostitis.

CPPS is often accompanied with articular restrictions or muscular pain (e.g. low back pain, pelvic girdle pain), indicating the attention for an extensive assessment of the musculoskeletal system [82]. We determined pain musculoskeletal origin in 88% of CPPS patients (n=23) [67]. The main areas of musculoskeletal pain were the lumbar and sacrococcygeal area [66]. Referred pain, hypertonic muscular activity and articular movement restrictions may maintain the viscous circle of symptoms related to CPPS. Differentiating all the symptoms in multiple systems, including the clinical signs of the musculoskeletal system can indicate a more appropriate approach in a holistic context, dealing with CPPS.

The evaluation as described in step 3 and 4 is highly recommendable although all suggested measures are not manageable by the urologist. A multidisciplinary team is needed to deal with the problem, including gynaecologists, neurologists, neurophysiologists, proctologists, sexologists, psychologists. Osteopathic physicians and physical therapists can be an aid assessing the patient in a holistic way, with attention to the interference between visceral and musculoskeletal symptoms (e.g. pelvic girdle pain, low back complaints, pain points, and fascial movement restrictions). Specialized centres are needed, with the thorough clinical investigation as an integral part of the assessment before the multidisciplinary team is consulted.

References

[1] Fall M, Baranowski AP, Elneil S, Engeler D, Hughes J, Messelink EJ, Oberpenning F, de C Williams AC; European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2010 Jan;57(1):35-48. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.08.020[2] Engeler D, Baranowski AP, Elneil S, Hughes J, Messelink EJ, Oliveira P, van Ophoven A, de C. Williams AC. Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain. European Association of Urology; 2012 (cited 13 July 2017). Available from: https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/24_Chronic_Pelvic_Pain_LR-March-23th.pdf

[3] Quaghebeur J, Wyndaele JJ. Chronic pelvic pain syndrome: role of a thorough clinical assessment. Scand J Urol. 2015 Apr;49(2):81-9. DOI: 10.3109/21681805.2014.961546

[4] Fall M, Baranowski AP, Elneil S, Engeler D, Hughes J, Messelink EJ, Oberpenning F, de C Williams AC. EAU Guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. European Association of Urology; 2008. Available from: https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/22_Chronic_Pelvic_Pain-2008.pdf

[5] Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, van Kerrebroeck P, Victor A, Wein A. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jul;187(1):116-26.

[6] Quaghebeur J, Wyndaele JJ. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and level of quality of life in men and women with chronic pelvic pain. Scand J Urol. 2015 Jun;49(3):242-9. DOI: 10.3109/21681805.2014.984325

[7] Engeler D, Baranowski AP, Borovicka J, Cottrell A, Dinis-Oliveira P, Elnei S, Hughes J, Messelink EJ, van Ophoven A, Reisman Y, de C. Williams AC. Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain: European Association of Urology. 2014 (cited 13 July 2017). Available from: https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/26-Chronic-Pelvic-Pain_LR.pdf

[8] Ke QS, Kuo HC. Pathophysiology of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Tzu Chi Medical Journal. 2015. 27(4):139-44. DOI: 10.1016/j.tcmj.2015.09.006

[9] van de Merwe JP, Nordling J, Bouchelouche P, Bouchelouche K, Cervigni M, Daha LK, Elneil S, Fall M, Hohlbrugger G, Irwin P, Mortensen S, van Ophoven A, Osborne JL, Peeker R, Richter B, Riedl C, Sairanen J, Tinzl M, Wyndaele JJ. Diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: an ESSIC proposal. Eur Urol. 2008 Jan;53(1):60-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.09.019

[10] Quaghebeur J, Wyndaele JJ. Bladder pain syndrome (BPS): Symptom differences between type 3C BPS and non-type 3C BPS. Scand J Urol. 2015;49(4):319-20. DOI: 10.3109/21681805.2014.982170

[11] Fall M, Baranowski AP, Fowler CJ, Lepinard V, Malone-Lee JG, Messelink EJ, Oberpenning F, Osborne JL, Schumacher S; European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol. 2004 Dec;46(6):681-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.07.030

[12] Giamberardino MA. Referred muscle pain/hyperalgesia and central sensitisation. J Rehabil Med. 2003 May;(41 Suppl):85-8. DOI: 10.1080/16501960310010205

[13] Giamberardino MA, Affaitati G, Lerza R, Vecchiet L. Referred muscle pain and hyperalgesia from viscera: clinical and pathophysiological aspects. Basic Appl Myol. 2004.14(1):23-8.

[14] Gebhart GF, Ness TJ. Central mechanisms of visceral pain. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1991 May;69(5):627-34. DOI: 10.1139/y91-093

[15] Yilmaz U, Liu YW, Berger RE, Yang CC. Autonomic nervous system changes in men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2007 Jun;177(6):2170-4; discussion 2174. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.144

[16] Pezzone MA, Liang R, Fraser MO. A model of neural cross-talk and irritation in the pelvis: implications for the overlap of chronic pelvic pain disorders. Gastroenterology. 2005 Jun;128(7):1953-64. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.008

[17] Ustinova EE, Fraser MO, Pezzone MA. Cross-talk and sensitization of bladder afferent nerves. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(1):77-81. DOI: 10.1002/nau.20817

[18] Kaya S, Hermans L, Willems T, Roussel N, Meeus M. Central sensitization in urogynecological chronic pelvic pain: a systematic literature review. Pain Physician. 2013 Jul-Aug;16(4):291-308.

[19] Wyndaele JJ. Investigating afferent nerve activity from the lower urinary tract: highlighting some basic research techniques and clinical evaluation methods. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(1):56-62. DOI: 10.1002/nau.20776

[20] Quaghebeur J, Wyndaele JJ. A review of techniques used for evaluating lower urinary tract symptoms and the level of quality of life in patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Itch & Pain. 2015;2: e659. DOI: 10.14800/ip.659

[21] McNaughton Collins M. The impact of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome on patients. World J Urol. 2003 Jun;21(2):86-9. DOI: 10.1007/s00345-003-0331-6

[22] Tripp DA, Nickel JC, Wang Y, Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Landis JR, Alexander RB, Schaeffer AJ, O'Leary MP, Pontari MA, Fowler JE Jr, Nyberg LM, Kusek JW; National Institutes of Health-Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network (NIH-CPCRN) Study Group. Catastrophizing and pain-contingent rest predict patient adjustment in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Pain. 2006 Oct;7(10):697-708. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.03.006

[23] Ku JH, Kim SW, Paick JS. Quality of life and psychological factors in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2005 Oct;66(4):693-701. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.050

[24] Melzack R. The McGill pain questionnaire: from description to measurement. Anesthesiology. 2005 Jul;103(1):199-202. DOI: 10.1097/00000542-200507000-00028

[25] Pollard CA. Preliminary validity study of the pain disability index. Percept Mot Skills. 1984 Dec;59(3):974. DOI: 10.2466/pms.1984.59.3.974

[26] Tait RC, Chibnall JT, Margolis RB. Pain extent: relations with psychological state, pain severity, pain history, and disability. Pain. 1990 Jun;41(3):295-301.

[27] Tait RC, Pollard CA, Margolis RB, Duckro PN, Krause SJ. The Pain Disability Index: psychometric and validity data. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1987 Jul;68(7):438-41.

[28] McNaughton Collins M, Pontari MA, O'Leary MP, Calhoun EA, Santanna J, Landis JR, Kusek JW, Litwin MS; Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. Quality of life is impaired in men with chronic prostatitis: the Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Oct;16(10):656-62.

[29] Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ Jr, Nickel JC, Calhoun EA, Pontari MA, Alexander RB, Farrar JT, O'Leary MP. The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Urol. 1999 Aug;162(2):369-75. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199908000-00022

[30] Propert KJ, Alexander RB, Nickel JC, Kusek JW, Litwin MS, Landis JR, Nyberg LM, Schaeffer AJ; Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. Design of a multicenter randomized clinical trial for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2002 Jun;59(6):870-6. DOI: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)01601-1

[31] Propert KJ, McNaughton-Collins M, Leiby BE, O'Leary MP, Kusek JW, Litwin MS; Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. A prospective study of symptoms and quality of life in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Cohort study. J Urol. 2006 Feb;175(2):619-23; discussion 623. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00233-8

[32] O'Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ Jr, Whitmore KE, Spolarich-Kroll J. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology. 1997 May;49(5A Suppl):58-63.

[33] Parsons M, Toozs-Hobson P. The investigation and management of interstitial cystitis. J Br Menopause Soc. 2005 Dec;11(4):132-9. DOI: 10.1258/136218005775544255

[34] Parsons CL. Diagnosing chronic pelvic pain of bladder origin. J Reprod Med. 2004 Mar;49(3 Suppl):235-42.

[35] Parsons CL, Dell J, Stanford EJ, Bullen M, Kahn BS, Waxell T, Koziol JA. Increased prevalence of interstitial cystitis: previously unrecognized urologic and gynecologic cases identified using a new symptom questionnaire and intravesical potassium sensitivity. Urology. 2002 Oct;60(4):573-8. DOI: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)01829-0

[36] Quaghebeur J, Wyndaele JJ. Comparison of questionnaires used for the evaluation of patients with chronic pelvic pain. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013 Nov;32(8):1074-9. DOI: 10.1002/nau.22364

[37] Cory L, Harvie HS, Northington G, Malykhina A, Whitmore K, Arya L. Association of neuropathic pain with bladder, bowel and catastrophizing symptoms in women with bladder pain syndrome. J Urol. 2012 Feb;187(2):503-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.036

[38] Arya LA, Harvie HS, Andy UU, Cory L, Propert KJ, Whitmore K. Construct validity of an instrument to measure neuropathic pain in women with bladder pain syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013 Jun;32(5):424-7. DOI: 10.1002/nau.22314

[39] Mathieson S, Lin C. painDETECT questionnaire. J Physiother. 2013 Sep;59(3):211. DOI: 10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70189-9

[40] George AK, Sadek MA, Saluja SS, Fariello JY, Whitmore KE, Moldwin RM. The impact of neuropathic pain in the chronic pelvic pain population. J Urol. 2012 Nov;188(5):1783-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.034

[41] Mathieson S, Maher CG, Terwee CB, Folly de Campos T, Lin CW. Neuropathic pain screening questionnaires have limited measurement properties. A systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015 Aug;68(8):957-66. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.03.010

[42] Keller ML, McCarthy DO, Neider RS. Measurement of symptoms of interstitial cystitis. A pilot study. Urol Clin North Am. 1994 Feb;21(1):67-71.

[43] Goin JE, Olaleye D, Peters KM, Steinert B, Habicht K, Wynant G. Psychometric analysis of the University of Wisconsin Interstitial Cystitis Scale: implications for use in randomized clinical trials. J Urol. 1998 Mar;159(3):1085-90.

[44] Porru D, Tinelli C, Gerardini M, Giliberto GL, Stancati S, Rovereto B. Evaluation of urinary and general symptoms and correlation with other clinical parameters in interstitial cystitis patients. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24(1):69-73. DOI: 10.1002/nau.20084

[45] Clemens JQ, Calhoun EA, Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Kusek JW, Crowley EM, Landis JR; Urologic Pelvic Pain Collaborative Research Network. Validation of a modified National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index to assess genitourinary pain in both men and women. Urology. 2009 Nov;74(5):983-7, quiz 987.e1-3. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.078

[46] Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524-32. DOI: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524

[47] Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Pain catastrophizing: a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009 May;9(5):745-58. DOI: 10.1586/ern.09.34

[48] Crawford JR, Henry JD. The positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004 Sep;43(Pt 3):245-65. DOI: 10.1348/0144665031752934

[49] Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Strom SE. The Chronic Pain Coping Inventory: development and preliminary validation. Pain. 1995 Feb;60(2):203-16. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00118-X

[50] Nordling J, Anjum FH, Bade JJ, Bouchelouche K, Bouchelouche P, Cervigni M, Elneil S, Fall M, Hald T, Hanus T, Hedlund H, Hohlbrugger G, Horn T, Larsen S, Leppilahti M, Mortensen S, Nagendra M, Oliveira PD, Osborne J, Riedl C, Sairanen J, Tinzl M, Wyndaele JJ. Primary evaluation of patients suspected of having interstitial cystitis (IC). Eur Urol. 2004 May;45(5):662-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.11.021

[51] Stöhrer M, Blok B, Castro-Diaz D, Chartier-Kastler E, Del Popolo G, Kramer G, Pannek J, Radziszewski P, Wyndaele JJ. EAU guidelines on neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2009 Jul;56(1):81-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.04.028

[52] Nee RJ, Jull GA, Vicenzino B, Coppieters MW. The validity of upper-limb neurodynamic tests for detecting peripheral neuropathic pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012 May;42(5):413-24. DOI: 10.2519/jospt.2012.3988

[53] Topp KS, Boyd BS. Peripheral nerve: from the microscopic functional unit of the axon to the biomechanically loaded macroscopic structure. J Hand Ther. 2012 Apr-Jun;25(2):142-51; quiz 152. DOI: 10.1016/j.jht.2011.09.002

[54] Topp KS, Boyd BS. Structure and biomechanics of peripheral nerves: nerve responses to physical stresses and implications for physical therapist practice. Phys Ther. 2006 Jan;86(1):92-109.

[55] Mizisin AP, Weerasuriya A. Homeostatic regulation of the endoneurial microenvironment during development, aging and in response to trauma, disease and toxic insult. Acta Neuropathol. 2011 Mar;121(3):291-312. DOI: 10.1007/s00401-010-0783-x

[56] Campbell JN, Meyer RA. Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Neuron. 2006 Oct;52(1):77-92. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.021

[57] Butler DS. The sensitive nervous system. Adelaide, Australia: NoiGroup Publications; 2000.

[58] Butler DS. Mobilisation of the nervous system. 7th ed. Melbourne: Churchill Livingstone; 1996.

[59] Shacklock M. Clinical Neurodynamics. A new system of musculoskeletal treatment. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2005.

[60] Greening J, Lynn B. Minor peripheral nerve injuries: an underestimated source of pain? Man Ther. 1998.3(4):187-94. DOI: 10.1016/S1356-689X(98)80047-7

[61] Nee RJ, Butler D. Management of peripheral neuropathic pain: Integrating neurobiology, neurodynamics, and clinical evidence. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2006. 7(1):36-49. DOI: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2005.10.002

[62] Schmid AB, Brunner F, Luomajoki H, Held U, Bachmann LM, Künzer S, Coppieters MW. Reliability of clinical tests to evaluate nerve function and mechanosensitivity of the upper limb peripheral nervous system. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009 Jan 21;10:11. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-11

[63] Devor M. Neuropathic pain and injured nerve: peripheral mechanisms. Br Med Bull. 1991 Jul;47(3):619-30.

[64] Curtis Nickel J, Baranowski AP, Pontari M, Berger RE, Tripp DA. Management of men diagnosed with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome who have failed traditional management. Rev Urol. 2007;9(2):63-72.

[65] Itza Santos F, Salinas J, Zarza D, Gómez Sancha F, Allona Almagro A. Update in pudendal nerve entrapment syndrome: an approach anatomic-surgical, diagnostic and therapeutic. Actas Urol Esp. 2010 Jun;34(6):500-9. DOI: 10.4321/S0210-48062010000600003

[66] Quaghebeur J. Research on diagnostic techniques used in CPPS patients. PhD thesis. Wilrijk, Belgium: Antwerp University; 2014.

[67] Quaghebeur J, Wyndaele JJ, De Wachter S. Pain areas and mechanosensitivity in patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a controlled clinical investigation. Scand J Urol. 2017 Jul 5:1-6. DOI: 10.1080/21681805.2017.1339291

[68] Katims JJ. Electrodiagnostic functional sensory evaluation of the patient with pain: A review of the neuroselective current perception threshold and pain tolerance threshold. Pain Dig. 1998;8:219-30.

[69] Quaghebeur J, Wyndaele JJ. Variability of pudendal and median nerve sensory perception thresholds in healthy persons. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015 Apr;34(4):327-31. DOI: 10.1002/nau.22565

[70] Quaghebeur J, Wyndaele JJ. Pudendal and median nerve sensory perception threshold: a comparison between normative studies. Somatosens Mot Res. 2014 Dec;31(4):186-90. DOI: 10.3109/08990220.2014.911172

[71] Mittal T, Kumar V, Khullar R, Sharma A, Soni V, Baijal M, Chowbey PK. Diagnosis and management of Spigelian hernia: A review of literature and our experience. J Minim Access Surg. 2008 Oct;4(4):95-8. DOI: 10.4103/0972-9941.45204

[72] Nazareno J, Ponich T, Gregor J. Long-term follow-up of trigger point injections for abdominal wall pain. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005 Sep;19(9):561-5. DOI: 10.1155/2005/274181

[73] Isherwood PJ, Rane A. Comparative assessment of pelvic floor strength using a perineometer and digital examination. BJOG. 2000 Aug;107(8):1007-11.

[74] Frawley HC, Galea MP, Phillips BA, Sherburn M, Bø K. Reliability of pelvic floor muscle strength assessment using different test positions and tools. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25(3):236-42. DOI: 10.1002/nau.20201

[75] Maigne JY, Doursounian L, Chatellier G. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine. 2000 Dec;25(23):3072-9. DOI: 10.1097/00007632-200012010-00015

[76] Simons DG, Travell JG, Simons LS. Travell & Simons' Myofascial pain and dysfunction the trigger point manual: Volume 1: the upper half of body. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

[77] McPartland JM, Simons DG. Myofascial trigger points translating molecular theory into manual therapy. J Man Manip Ther. 2006. 14(4):232-9. DOI: 10.1179/106698106790819982

[78] Anderson RU, Wise D, Sawyer T, Chan C. Integration of myofascial trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training treatment of chronic pelvic pain in men. J Urol. 2005 Jul;174(1):155-60. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000161609.31185.d5

[79] Wise D, Anderson R. A Headache in the Pelvis. A new understanding and treatment for prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndromes. 4th ed. Occidental, CA: National Center for Pelvic Pain Research; 2006.

[80] Carter JE. Chronic Pelvic Pain Diagnosis and Management. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001.

[81] Epstein O, Perkin D, Cookson J, De Bono D. Clinical Examination. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2003.

[82] Tu FF, Holt J, Gonzales J, Fitzgerald CM. Physical therapy evaluation of patients with chronic pelvic pain: a controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Mar;198(3):272.e1-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.002