Online art therapy for breast cancer patients. A feasibility study on acceptance and psychosocial health during cancer treatment

Sabine C. Koch 1,2,3Harald Gruber 1

Pauline Thielen 1,4

Michael Neumann 5

Verena Wilberg 5

Anita Kamra 5

Andree Faridi 5

Rupert Conrad 5,6

Katja Bonnländer 7

Dimitri M. L. Van Ryckeghem 4,8,9

Ingo Schmidt-Wolf 5

1 Research Institute for Creative Arts Therapies (RIArT), Department of Creative Arts Therapies and Therapy Sciences, Alanus University for Arts and Social Sciences, Alfter, Germany

2 School of Health, Education, and Social Sciences, SRH University Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

3 Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, CATRU, University of Melbourne, Australia

4 Department of Clinical Psychological Science, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands

5 Center for Integrated Oncology (CIO) Aachen Bonn Köln Düsseldorf, Department for Integrated Oncology, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany

6 Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Muenster, Germany

7 Art Therapy, HKS Ottersberg, Ottersberg, Germany

8 Department of Behavioural and Cognitive Sciences, University of Luxembourg, Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg

9 Department of Experimental-Clinical and Health Psychology, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

Abstract

Background: This study assesses psychosocial health and acceptance of intervention and scales for breast cancer patients in an eight-week online art therapy (AT) during cancer treatment. The study aims to demonstrate feasibility of the AT online intervention for the participating patients to conduct a randomized controlled trial (RCT) on the same research question upon successful completion of the feasibility trial.

Methods: In this randomized feasibility study at University Hospital Bonn, we compared a group of women with breast cancer receiving online AT while in oncological treatment (n=6) to a treatment as usual (TAU) control group (CG; n=6). We measured psychosocial health (anxiety, depression, distress, and quality of life) with the EORTC-C30, WHO-BREF, POMS, and the HADS. After each session, we also measured distress, happiness, and the experience of beauty. Acceptance of the intervention was assessed on three scales and with open questions.

Results: The acceptance of the online AT was very good. Acceptance of scales and randomization was also given. Peliminary, descriptive statistics revealed trends for benefits of art therapy for all major clinical outcomes: Patients reported a decrease in anxiety and distress, and an increase in QoL (on EORTC-C30 and WHO-BREF), experience of beauty, and happiness after the intervention compared to the CG.

Discussion: Online art therapy is feasible and offers broad and safe creative arts therapies and access for breast cancer patients undergoing oncological treatment, with no adverse events reported. Findings on group differences are preliminary and exploratory, given the underpowered sample size. An adequately powered RCT can follow to investigate the effectiveness of online AT for this patient group. Creation and narration in art, accompanied by an art therapist, may contribute to shift the experience of patients in cancer treatment from passive-enduring to active-creating.

Keywords

art therapy, creative arts therapies, breast cancer, online intervention, acceptance, quality of life, experience of beauty

1. Introduction

Being diagnosed with cancer and the treatment associated with it leads to drastic changes in the life of patients and requires profound adjustments [14]. Overnight the patient is in a situation, where existential questions are prone to arise [13] What is going to happen now? Am I going to die? How can I live my life to the fullest from here? The disease itself entails various effects of negative impact on the patients’ quality of life (QoL) and well-being. Some of the symptoms or adverse aspects may be experienced as identity- or even life-threatening, for instance, pain, weakness, fatigue, hair loss, permanent post-surgical scars, side effects of treatments, and permanent physical changes. All of them have the potential to threaten the patients' psychological health, both in the short and in the long term [21].

Breast cancer in women is the most common type of cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death in women worldwide. In 2020, the WHO reported an estimated 2.3 million women to be diagnosed with breast cancer, and 685 000 deaths globally [47]. In Germany, there are approximately 71.357 incident cases of breast cancer in women per year, and 18.519 deaths [48]. Both breast cancer itself and the related treatment cause physical limitations, and some patients feel entirely alienated from their bodies. Physical and psychological symptoms that come with the disease reduce the quality of life in patients [5]. In the context of the disease, it may be hard to put all of the overwhelming feelings into words. The psychosocial needs of breast cancer patients, thus, are manifold, and creative arts therapies (CATs) may be beneficial to meet those needs.

1.1 Online art therapy for breast cancer patients

Approaches specifically suited to address the nonverbal expression and processing of the mentioned conflicts are creative arts therapies (art-, music-, dance-, drama-, and poetry therapy) [14]. There is vast evidence for art-, music- and dance therapy as supportive treatment for cancer patients [1], [5], [6], [7]. All three modalities just recently received a level-of-evidence recommendation in the German medical guideline for psycho-oncology [30].

Art therapy (AT), one of the creative arts therapies (CATs), and as such a nonverbal treatment approach increasingly used to improve the quality of life and well-being related to trauma, illness, and treatment experiences of cancer patients, is suited to improve overall well-being [12]. In general, creative arts therapies (CATs) work in a resource-oriented manner with artistic means and therapeutic accompaniment to stabilize patients with a wide variety of clinical characteristics [16], [15], [39]. As a psychosocial form of treatment in oncology, CATs demonstrate an increasing evidence-base [1], [6], [7], [21], [24]. CATs are particularly suited for treatment in existential life situations [29]. They allow patients to integrate contradictory sensations, emotions, and thoughts, communicate them nonverbally and verbally in a protected setting, and thus bring them to a reasonable conclusion [29]. As a result, they achieve, for example, anxiety and stress reduction and can improve the patient’s quality of life [5]. Usually, CATs are so far mostly applied in rehabilitative contexts [14], even though they show good results also during the actual cancer treatment [11], [38], [41]. Art therapy (AT) yields good metal health results for cancer patients [38], [40], Czemanski-Cohen and colleagues [9] found an increase in acceptance of emotion, emotional awareness, and depressive symptoms after art therapy compared to a placebo control group (mandala painting). There is, however, a gap in the literature on the benefits of AT for patients under cancer treatment. Inspired by the studies of Ho et al. conducted in dance therapy, the current study addresses this gap, with a particular focus on feasibility for a subsequent RCT study on art therapy with the same population. This study thus investigates the importance and effectiveness of art therapy after the initial diagnosis of breast cancer during active oncology treatment. It was a collaboration of the Research Institute for Creative Arts Therapies (RIArT) at Alanus University of Arts and Society and the CIO (Center of Integrated Oncology) at University Hospital Bonn. This study focuses on art therapy provided in an online format, which resulted out of the necessity of it being conducted during the COVID-19 pandemia.

In the year of the COVID-19 outbreak, Wang et al. [46] identified remarkable significant temporal changes in the levels of stress (+8,1%), anxiety (+28,8%), and depression (+16,5%) in the general population [46]. The Mental Health Foundation in the UK recommended to increase the evidence-informed psychotherapeutic digital mental health interventions, particularly for vulnerable patient groups [34]. Findings suggest that online art therapies provided new ways of communicating and reported improved health outcomes for different populations [18], [37]. Odunlade et al. [37] found that for 81.5% of their respondents, online arts psychotherapies had a sustainable impact on preventing crisis and deterioration. Online therapy is an effective means to reach those patients who would otherwise not have access to supportive treatment [25].

1.2 The present study

The study evaluated psychosocial outcomes and acceptance of art therapy as a supportive therapy for breast cancer patients in active cancer treatment compared to a control group -- a waiting list group receiving treatment as usual (TAU) in the critical intervention period, patients in both groups were travelling to the CIO-Center at University Hospital Bonn for their treatment at different stages from their homes. They participated in the online AT sessions from their homes. During the intervention period they were not offered any other psychosocial therapy modality; however, psychosocial consultation was available to them on demand. Next to the patients’ symptom changes on depression, anxiety, distress and quality of life, we assessed the experience of beauty and happiness as relevant protective factors. The research was conducted as a feasibility study preceding a more extensive study at the CIO of University Hospital Bonn, Germany (CIO = Center of Integrated Oncology) in cooperation with the RIArT (Research Institute of Creative Arts Therapies) at Alanus University, Bonn.

In this feasibility study, improvement in psychosocial outcomes was expected. Psychosocial outcomes is used as an umbrella term that summarizes the different outcomes of the study: symptom reduction concerning distress, anxiety, and depression, and an increase in quality of life, the feeling of happiness, and the experience of beauty. The study additionally conceptualized the feeling of happiness and the experience of beauty as two therapeutic factors. The feeling of happiness is a key element in the restitution of an improved quality of life [3]. The experience of beauty as a form of aesthetic experience is an important health indicator and a joint therapeutic factor of the CATs [27], [10]. It is assumed to counteract cancer-related adversities [21], [22], because moments of beauty serve an important protective function of restoration, resilience, and resourcing [26], [28].

Simultaneously, the acceptance of the intervention and scales, patients’ needs, and, in case of discontinuation, dropout reasons were assessed in order to optimize the fit for our targeted patients in the main trial. One goal was to create structures for the systematic anchoring of CATs in both the face-to-face and virtual context in integrative oncology. The state of the present knowledge mainly stemming from AT in rehabilitative oncological contexts – with the knowledge gap on how the acceptance of online AT under active cancer treatment was –, lead to the following two research questions: In breast cancer patients in acute treatment, (1) What is the potential impact of online AT on patients’ psychosocial health? We formulated two hypotheses H1: AT decreases anxiety and depression and increases of quality of life compared to the TAU control group; and H2: AT decreases stress, and increases in experience of beauty and happiness in the process of the intervention and (2) How is the patients’ acceptance of art therapy? (assessed with three scales, four open questions and observations; s. “Methods”).

2. Methods

2.1 Sample and study design

An art therapist, a nurse, and the physicians in the hospital’s oncology department approached oncological patients, informing them about the study’s aim, type, and procedure. Further advertisements in regional newspapers and flyers recruited patients from outside the hospital providing the opportunity to participate in the online feasibility study. The resonance was high. All incoming patients were offered a virtual information session with the study’s art therapist to jointly decide about their participation.

Inclusion criteria were adults (age 18+) with breast cancer before or during active oncology treatment. Participants needed to be verbally, physically, and mentally able to take part in art therapy, to complete the patient questionnaire independently, and to provide written informed consent. To guarantee an appropriate working environment during the therapy sessions, a limit of six patients per group was applied to the intervention group. Accordingly, the final sample size included a total of twelve participants, six in each condition.

The patients were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (IG) (n=6) or the control group (CG) (n=6) using random sequence generation in Excel 16.0.1 by a blinded team member of the CIO Bonn, with all patients being in treatment there. Participants in the control group were offered to later take part in the main study, to ensure their access to art therapy. The CG was thus a wait-list control.

The group members were all female with a mean age of 53.2 years (SD=10.7, range 37–69), all ethnically of European descend. The average date of diagnosis of participants was the year of 2019 (SD=1.6, range 2016–2021). None of them was diagnosed with a mental health disorder. Additionally, all of them reported that they had never participated in art therapy. On a scale from 1 (very low) to 10 (very strong), the individuals reported on average that the disease had a level of strain of 7.8 (IG=8; CG=7.6). All the participants had some diverse artistic experiences, e.g., dance, photography, art, theater, etc. All of them indicated that art was one of their preferences. On a scale from 1 (not at all) to 6 (a lot), the average active experience in art was 2.9 (art making), and the average passive experience in art was 3.7 (art reception), with no significant differences between groups.

2.2 Procedure

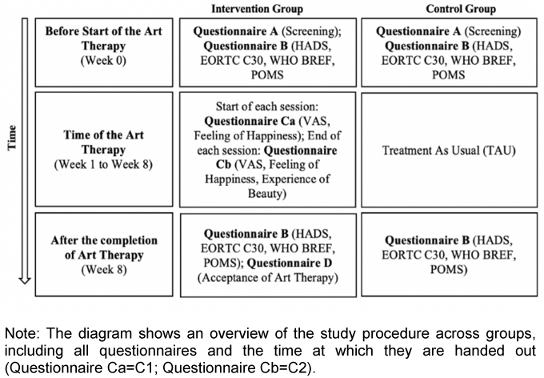

The study was conducted over a period of nine weeks. Before the intervention group started with the art therapy, the entire sample (n=12) received a letter with Questionnaires A and B (week 0) (see Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). The individuals of the intervention group (n=6) additionally obtained a package with the materials and had a one-on-one online conversation with the art therapist to get to know each other. All participants were asked to fill in the two questionnaires and to send them back to the University Hospital, because they served as baseline measures. During the entire period, the control group (n=6) received treatment as usual (TAU) and did not participate in any art therapy session for the course of this study. All patients received chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Figure 1: Overview of the time frame and questionnaires

2.2.1 Overview

With the beginning of week one, the intervention group patients started to receive eight weeks of online art therapy, conducted by an academically trained female art therapist. All patients obtained access to a virtual meeting room of University Hospital Bonn to guarantee data safety. The password protected meeting room was especially created for the therapy sessions. It worked like a common video call, where the individuals could speak to and see each other through their webcams. In addition, the therapist offered the possibility to be contacted individually, if there were any personal issues (week 1 to 8) (see Figure 1 [Fig. 1]).

The two-hour sessions took place once a week every Thursday. Every session had its own topic which was introduced by the art therapist, a white middle-aged woman from Akademie der Bildenden Künste München, Germany, with many years of experience. In general, her work can be described as opening a new space outside of language. The process of creation and the artistic rhythm were the focus of the therapy. The attention of the individuals was able to fluctuate between their feelings, for example anxiety and pain, and the creation of art during the process. The goal of the therapist was to be an active listener and to hold the individual experience with the appropriate therapeutic attitude, careful to neither victimize patients nor trivialize their situation. One important aspect of the therapist’s attitude was to show her appreciation of the individuals’ distress, and to recognize patients’ perception of the progressive impulses that evolved from the movement in their life with cancer, and that often appeared in their arts expressions. Establishing an atmosphere based on appreciation and mutual respect, the therapist created a piece of art herself during the sessions, thus mirroring reactions she observed in the group.

2.2.2 Intervention description: content of the sessions

- The first session of art therapy focused on the workplace of every individual, portraying their working environment in a painting. The session was used to take advantage of the joy, triggered by the creative process and to build fellowship in the group.

- The second session was designed for the online framework. The participants set up their webcam in such a way that you could only see their hands while painting. Then, one participant started painting on impulse being imitated by the others, using the same shape and color. Six variations of a picture emerged in this way.

- The third session captured the process of communication between the inside and outside world. The participants had to work with clay keeping their eyes closed, thus concentrating on the creative act, and thereby forgetting their painful experiences.

- The fourth session was dedicated to the topic of time and temporality. During the creation of their art, the group had the chance to discuss the topic of time itself and time that goes beyond our life, in their confrontation with the finite nature of life. Further, they found an analogy with the idea of love.

- In the fifth session, the participants made a collage of wishes. It was primarily made from different pieces of art, and they had to imagine what the people in the piece of art might wish for. They could also associate the work with their own wishes and needs.

- The sixth session supported the togetherness as a group. The participants painted a “group tree” (see Figure 2 [Fig. 2]). Every participant painted one piece of the tree and the therapist combined the parts in one large piece of art.

- The topic of the seventh session was “to be for oneself and to be with oneself”. The participants had an artistic and verbal exchange about this topic. One point was to discuss what qualities the state of being for oneself can have (e.g., being free), thereby expressing individual opinions and learning from each other.

- The focus of the last session was on making a thought experiment, imagining oneself as a tree and expressing one’s ideas in art. The goal of the last session was to create an awareness of the patients’ current situation of their lives with cancer. For further details on the intervention please address authors.

2.2.3 Data collection

Before and after each of the eight sessions, the participants received an e-mail with a link for an online survey [42]. The questionnaire that was filled in before every therapy session (Questionnaire C1) contained a measure to evaluate the level of stress and the experience of happiness. The questionnaire that was filled in after every therapy session (Questionnaire C2) contained the same questions as Questionnaire C1, with additional questions regarding the therapeutic factors of art therapy. Moreover, the preliminary end of the study was characterized by two questionnaires, which were sent to the participants via regular mail. One questionnaire was only given to the intervention group asking about their acceptance of the art therapy (Questionnaire D). The other one was sent to both groups: the same questionnaire they had already received at the beginning of the study (Questionnaire B) (see Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). All of the questionnaires are described in more detail in the next section.

2.3 Materials and instruments

2.3.1 Pre-/post-measures (before the start and after the end of art therapy)

Questionnaire A

The screening questionnaire (Questionnaire A) contained 15 questions regarding demographic data of the patients, their cancer diagnosis and their previous experiences with art and art therapy. Demographic data, including marital status, year of birth, highest level of education and profession. Question five to eight asked about diagnosis data, treatment, and perceived strain. The questions about perceived strain level included a scale from 1 (very low) to 10 (very high) of how strongly the individual perceives the disease as an affliction, and two open-ended questions on which participants were able to indicate, which physical and psychological burden they wanted to be addressed. The remaining questions asked about the individuals’ experience with art (active and passive) and art therapy, and the value art had for them. The last question clarified whether any of them had been diagnosed with a psychological disorder. An overview is provided in the section Sample.

Questionnaire B

The patients of the intervention and control group received Questionnaire B at two points in time: (1) before starting art therapy, and (2) after eight weeks of art therapy or TAU, respectively (see Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). The questionnaire contained four standardized surveys (HADS, POMS, EORTC C-30 & WHO BREF) that measured the main variables of the study, anxiety, depression, and quality of life. Anxiety and depression were assessed by the German version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [19]. Quality of life was assessed by three surveys. The German short version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) [32]), the Core Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ-C30) [35] and the WHOQOL BREF [8] from the World Health Organization Quality of Life group [44], [45]. The questionnaires assess various aspects of health-related quality of life. In this feasibility study, it was important to assess which of the QoL measures is most suited and effective in this context.

Anxiety and depression

The HADS is a self-report questionnaire for depression and anxiety symptoms [19]. It includes 14 items with four-level response options (0 low to 3 high), seven of which relate to anxiety and seven to depression, alternating thematically. Five items of the scale are reverse coded [23]. An anxiety score and a depression score are formed by adding the individual judgments [19]. In the end, the total scores for each subscale range from 0 to 21, where higher scores indicate a higher level of symptoms [23]. A cut-off value of 8 or above is used in the clinical context [4]. The German version of the HADS is a valid and reliable statistical measurement, with high internal consistencies for both, the anxiety (Cronbach’s α=.80–.93) and the depression subscale (Cronbach’s α=.81–.90), a high retest reliability (r=.81–.89) and stability to withstand situational influences [20], [23]. For this study, Cronbach’s α=.84 was found.

Quality of life (QoL)

The WHOQOL-group defines quality of life as a person’s perception of his or her place in life in relation to their goals, expectations, norms, concerns, and the context of their culture and its values. Different aspects such as the physiological and physical aspect can be assessed using various questionnaires. This study focuses on general quality of life. Thus, it does not consider the different subscales of the questionnaires for the computations.

WHOQOL BREF

The questionnaire allows tracking the global-health status of patients in a disease-independent way. It shows how patients feel and cope in everyday life [36], [44], [45]. The WHO BREF, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), includes 28 items in total. Twenty-four of those items can be divided into four domains (physical health, psychological health, social relationships, environment). All items are answered on a Likert-scale ranging from 1 (never/not at all/very bad/very unsatisfied) to 5 (always/completely/very good/very satisfied), with a higher score indicating a better QoL. Previous studies found a high internal consistency of the WHOQOL BREF with a Cronbach's alpha between .57 and .88, and a good validity [8]. For this study a good reliability was found, with Cronbach’s α=.82.

EORTC QLQ-C30

The questionnaire contains 30 items which were all rated on a Likert-scale. Items one to 28 employ a Likert-scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). They compromise different subscales, such as emotional or social functioning. Items 29 and 30 build a global health and QoL-scale, ranging from 1 (very bad) to 7 (excellent). Those two items are reverse scored. Notably, none of the subscales are recorded separately in this study. Mean scores of the scale are calculated, with a lower score indicating a better quality of life [23]. The measurement had a very good validity, as well as a high reliability in previous studies (Cronbach’s a=.72–.86) [35]. In this study the questionnaire showed a good reliability, with Cronbach’s α=.87.

POMS

The psychological component of quality of life was measured by the German version of the Profile of Mood States [32]. It is a self-report scale for the assessment of changing, transient mood states. They are applied to quantitatively assess therapeutic intervention effects on mood states and mood changes throughout the observation. The POMS consists of 35 adjectives, rated by the patients to describe their mood states during the last 24 hours (e.g., sad, energetic, angry) [17]. For this purpose, each adjective is rated on a seven-point rating scale from 0 (not at all) to 6 (very strong) [32]. Seven of the items are reverse scored (4, 8, 12, 20, 28, 30, 34). Mean scores of the scale are calculated with a lower score indicating a higher QoL. Previous studies report a high internal consistency of the shortened version of the POMS (Cronbach’s α=.91), and the discriminant and divergent validity of the questionnaire [2]. This study found a very good reliability with Cronbach's α=.92.

Questionnaire D

Acceptance

Questionnaire D was specifically created for this feasibility study to assess the acceptance of the therapy's virtual setting. The questionnaire contains seven questions, a mixture of open-ended and closed questions on a Likert-scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 6 (a lot). Four out of those seven questions were open-ended and examined feedback regarding the art intervention (e.g., What was good/bad?). They were used as food for thought and to provide an insight into participants’ perceptions of how online interventions work. The closed questions of the questionnaire specifically asked how the digital format of the art therapy was perceived. Furthermore, question seven contained different sub-questions to address specific therapeutic factors of the intervention.

2.3.2 Process measure (before and/or after each art therapy session)

The process measures (Questionnaire C1 and C2) were administered before and after every art therapy session by the intervention group via an online link to the website SoScisurvey [42]. The questionnaires had been created for this study to establish the immediate effects of the therapy sessions on the psychosocial health of the patients. Questionnaire C2 included a repetition of questions one and two of Questionnaire C1 and additional questions about the therapeutic factors of arts therapies [26].

Questionnaire C1

The questionnaire (C1) contained two questions and was completed before each art therapy session. The first item was the Distress Thermometer (DT) [33]. This is a one-item self-report measure about the current distress of the patient (Lim et al., 2014). Patients rate their distress of the last week on a ten-point Likert-Scale, ranging from 0 (not stressed at all) to 10 (extremely stressed). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) rated the scale as an effective assessment to administer distress in cancer patients [31]. For clinical assessment, a score of five is the cut-off that indicates high distress of the patients to be understood as a warning signal [33]. The second item was asking for the level of happiness at the present moment on a scale from 0 (very low) to 6 (very high).

Questionnaire C2

Questionnaire C2 was used after each session of the online art therapy (Questionnaire C2) [26]. Besides the two questions from Questionnaire C1, it contained additional questions on various therapeutic factors of art therapy and a question on the acceptance of the therapy (‘The art therapy has done me good/was beneficial for me’) (Question 3–11). In this study, only the therapeutic factors of the experience of beauty on a scale from 0 (very low) to 6 (very high), and the feeling of happiness were considered.

2.4 Data analysis

The study used a randomized single-factorial control-group-design in which the control group (TAU) was compared to the intervention group (online art-therapy session). Using G*Power (version 3.1.9.2), we estimated that a sample size of 58 participants would be needed to reach a power of .80. Because of the smaller sample size and the non-normal distribution of some variables, we employed nonparametric tests. The conducted MANOVA was exploratory and intended to identify potential covariates for future studies. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (WSR) and MANOVA were done with the Statistical Package of the Social Sciences program (SPSS; Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA; version 27.0). Descriptive statistics of the sample were examined, and reliabilities of the questionnaires computed. For all hypotheses tests, the alpha-level of .05 was chosen.

A test of normality showed that the population was normally distributed on all measures, except for depression (p=.045) and the quality of life, measured by the WHO BREF (p=.036). T-tests for anxiety, POMS, and the EORTC C30 were applied to check the successful randomization of the sample. A Mann-Whitney-U-Test, computed to check the randomization of depression and QoL of the WHO BREF, was non-significant. Thus, the randomization was successful for these measures. Before the analysis of the hypotheses, an explorative MANOVA was conducted. It considered age, the level of burden and the active and passive experience with art as possible covariates. By providing insights into the sample and results this parametric measure added value to the main study. Missing data was rare and single missing values were replaced with the scale means. An exception was the missing last page of the questionnaire, where we called all participants once more to ask for the missing items.

Hypothesis 1 was analyzed with Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (WSR) for the different variables of psychosocial health. We computed changes between the pre- and post-measurements of anxiety, depression, and QoL symptoms for both groups. Because it is not possible to measure interaction effects with SPSS in this non-parametric test, we analyzed the symptom-changes for both, the IG and CG separately to compare the groups afterwards by describing the difference scores (DS). Moreover, baseline measures of both groups were compared with Mann-Whitney-U-Tests to check whether they showed a significant difference in symptom levels at the pre-tests. Summarized, the calculations considered the effect of art therapy on the outcome measures (QoL, anxiety and depression symptoms) in individuals of the IG compared to the CG, who did not receive AT (waiting group).

Hypothesis 2 was also analyzed with WSR tests. The mean scores of distress and the feeling of happiness were calculated for Questionnaire C1 and C2. For the experience of beauty, the mean scores of sessions one and eight were used. Thus, we tested whether the art therapy sessions had an impact on the psychosocial health of the patients in the IG, defined by stress and two therapeutic factors of interest. Descriptive statistics show the development of the perception of beauty over eight weeks.

Finally, the acceptance of the online environment for the art therapy was explored via descriptive statistics. Answers to the open questions of Questionnaire D are discussed in the results section.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics of group comparisons (H1: IG vs CG)

3.1.1 Explorative MANOVA

Before the analysis of the hypotheses, an explorative MANOVA was conducted. The multivariate test considered age, strain level, and the active and passive experience with art as possible covariates. All variables were selected for this calculation against the background, because they could act as possible covariates and exert an influence on the subsequent results.

Results suggest the age of the participants to be a significant covariate in the explorative analysis (p=.029). The active experience with art, which the patients had before the start of the therapy (p=.087), and the group variable (IG vs. CG) (p=.057) show a tendency to be significant covariates. The other covariates were identified as non-significant. The experienced strain of the patients showed the least significant influence on the psychosocial health in this analysis (p=.267). Group comparisons between IG and CG will be presented next.

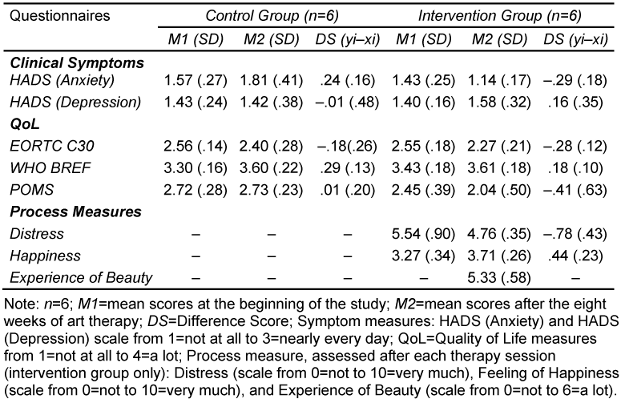

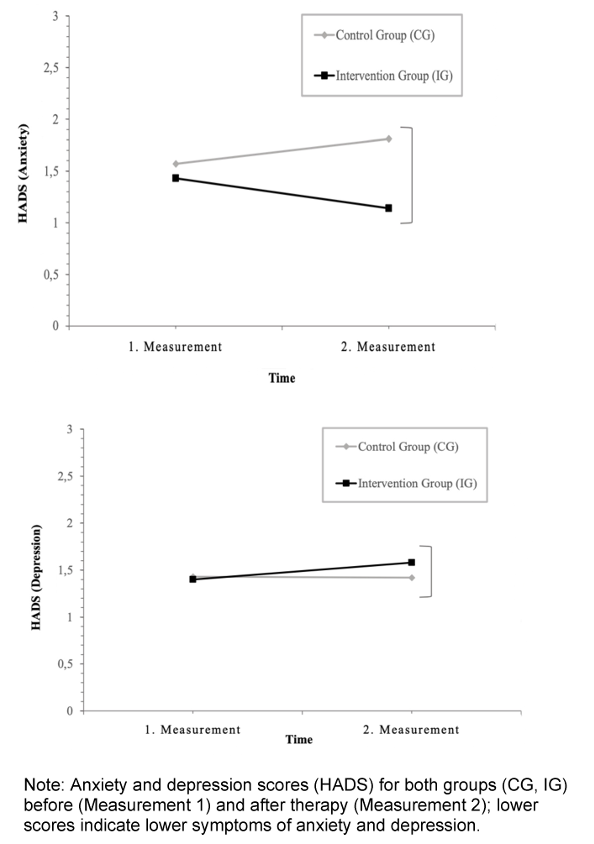

3.1.2 Anxiety and depression (HADS)

Descriptive values (means, standard deviations, and difference scores) of the HADS for both groups before (Measurement 1) and after (Measurement 2) the eight weeks of treatment, and the difference scores (DS) for each value, are displayed in Table 1 [Tab. 1]. Means were calculated for each subscale (seven items each). Higher values exemplify stronger expressions of anxiety and depression (0=not at all; 3=nearly every day). Mann-Whitney-U-Tests were applied to check the baseline measures of both anxiety, and depression. Neither the scores for anxiety (p=.699), nor for depression (p=.936) were significantly different between the two groups.

Table 1: Means (SD) and difference scores (DS) across measurement and condition of the questionnaires on anxiety, depression, quality of life (QoL) and process measures (distress, happiness, experience of beauty)

Results show that individuals in the IG experienced a reduction in anxiety symptoms after receiving eight weeks of art therapy (DS=–.29), whereas participants in the CG experienced an increase in their anxiety symptoms (DS=.24). However, they also show that the depression symptoms of the IG are slightly increased after the eight weeks (DS=.19), whereas the CG shows nearly no difference in depression symptoms (DS=.01).

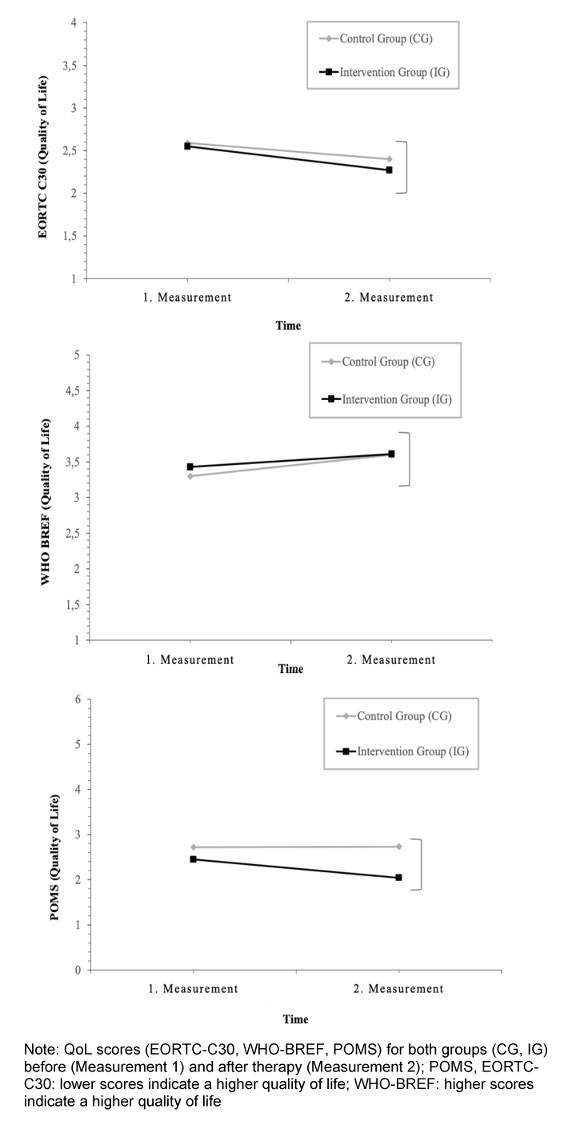

3.1.3 Quality of life (EORTC C30, WHO BREF, POMS)

Descriptive values (M, SDs, and DSs) of the different quality of life measurement scores before (Measurement 1) and after (Measurement 2) the intervention for both groups are displayed in Table 1 . No significant differences were found for the baseline measures of the three QoL questionnaires (EORTC: p=.818; WHO: p=.631; POMS: p=.630). For the EORTC C30, a lower score indicates a higher quality of life (1=not at all; 4=a lot). Individuals in the intervention group (DS=–.28) showed a higher QoL increase than those in the control group (DS=–.18).

The scale of the WHO BREF ranges from 1 (not at all) to 4 (complete), with a higher score indicating a better QoL. Results in Table 1 [Tab. 1] display an increase in QoL for both groups over the eight weeks. However, they also demonstrate that the CG (DS=.29) had a higher increase in QoL symptoms over the eight weeks than the IG (DS=.18). The last measurement for QoL was the German short version of the POMS. All 35 items had a scale range from 0 (not at all) to 6 (very strong), with a lower score indicating a higher QoL. Table 1 [Tab. 1] illustrates that almost no differences can be found in the measures for the CG (DS=–01). The QoL symptoms for the IG have decreased over the eight weeks (DS=–.41).

3.1.4 Distress, happiness, experience of beauty (questionnaires C1/C2)

Descriptive values (M, SD, and DS) for the variables of interest in the process measurements are displayed in Table 1 [Tab. 1]. Distress was measured on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very strong). The feeling of happiness and the experience of beauty were measured on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 6 (a lot). Results suggest that the individuals in the intervention group experienced less distress (DS=–.78) and an increased feeling of happiness (DS=.44) after the art therapy sessions. Furthermore, participants had a higher experience of beauty after the therapy sessions (M=5.33). The mean experience of beauty after the sessions was in the upper range of the scale (M>3) with a stabilization over time, suggested by the mean value of 5 for the last four sessions. Yet, a small N limits the results.

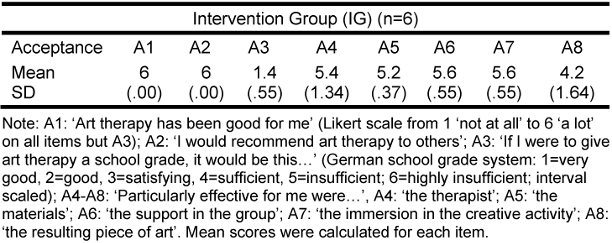

3.2 Results of acceptance

The mean values and SD of the acceptance questions (Questionnaire D) are displayed in Table 2 [Tab. 2]. All questions were answered on a scale from 1–6. Item A3 asked for a grade for the art therapy. Thus, a lower value indicates a better score (M=1.4). For the other items a higher value stands for a better result. The results for items A1 and A2 were outstanding. All individuals would recommend art therapy to others (M=6). All of them stated that the art therapy has been of great value for them (M=6). Since the first two items showed no variance at all, the scale could not be validated. Items A4 to A8 ask for the effectiveness of specific aspects of the intervention. All aspects were rated as highly positive. Particularly, the support in the group (M=5.6) and the immersion in the creative activity (M=5.6) were regarded as very effective. The least important factor was the final piece of art itself (M=4.2), speaking to the higher importance of the process related change factors.

Table 2: Mean values of acceptance, measured after eight weeks of art therapy

Some of these numeric results are reflected in the open questions of the questionnaire What was good?, What was bad?, Particularly effective for me were…, Suggestions for improvement… and I think that the therapy works through the following mechanisms…. Here, the experience of participation and the exchange with other individuals suffering from breast cancer were mentioned most frequently. Further, individuals often reported they had appreciated the therapist and the appreciative atmosphere.

Many participants liked the creative working process, reporting that it helped them to forget their stressful thoughts of the disease for the two hours (e.g., The concentration on the creative work helped me to forget my feelings about the disease and gave me strength. The creative contention with the disease helps me a lot.). The therapist was described as empathic, sensitive, trustful, and concerned about the patients’ well-being. Suggestions for improvement are to continue the art therapy for a longer period of time and to provide an opportunity to stay in touch with the other group members. As a downside to the online setting, two participants noted that they could not see each other's artwork live and that they would have liked to meet the participants in person. In sum, we observed feasibility of the intervention, online format, randomization and scales.

3.3 Inferential test to discover trends in the data

Hypotheses tests were conducted despite the insufficient power to detect differences on a significant level due to the small sample size. It is therefore indicated to focus on the descriptive differences in addition to the reported inferential statistics to interpret the results.

Regarding hypothesis 1, we tested the effect of art therapy on psychosocial health, defined by a symptom reduction in anxiety and depression and an increase in QoL comparing IG and CG. We computed multiple WSR tests to calculate symptom changes per group. There were no significant baseline differences between the groups on the measurements of interest (HADS; EORTC-C30; WHO-BREF; POMS). We found no significant changes between the IG and the CG on any of the outcomes (between-group). Figure 3 [Fig. 3] and Figure 4 [Fig. 4] visualize the changes in both groups for the five outcome measures. Most findings show that IG participants experienced larger changes in outcome measures than CG participants: IG participants had a stronger increase in QoL and a stronger decrease in anxiety and depression than individuals in the CG after the eight weeks of treatment (see Figure 3 [Fig. 3] and Figure 4 [Fig. 4]).

Figure 3: Quality of life scores across measurement and condition

Figure 4: Anxiety and depression scores across measurement and condition

For hypothesis 2, we tested the changes in psychosocial health in the form of changes in the process measurement. Three WSR-tests were conducted for the variables of interest. Results suggest that the n=6 participants do not show a significant decrease in distress (p=.137), or feeling of happiness (p=.173) after the art therapy sessions. The last WSR-test tested the difference in the perception of beauty between the first and last therapy session. Three individuals (n=3) were included and all of them showed an increase from session one to eight, that was not significant (n.s.) but displayed a clear trend (p=.051). In sum, despite the n.s. findings, a positive trend of all sub-measures of the process measurement for psychosocial health was observed, as displayed in the descriptive statistics (Table 1 [Tab. 1]) and the results of the WSR tests. Acceptance was very high throughout.

4. Discussion

The study investigated the effects of an eight-week art therapy session on the psychosocial health of breast cancer patients and their acceptance of online art therapy. It was conducted as a feasibility study prior to a fully powered main trial at the University Hospital Bonn. Given the underpowered sample, findings are preliminary and exploratory. Results suggest a significant increase of QoL on the EORTC-C30 scale. On the descriptive level, results suggest that eight weeks of online art therapy positively impact patients’ anxiety and depression levels, their QoL, experience of beauty, and distress. The IG had higher difference scores for all measurements, except for the depression scale of the adapted HADS. With a sample size of twelve participants no interaction effects could be tested. All results should be interpreted with caution, especially because only non-parametric tests were used.

4.1 Hypotheses testing

Hypothesis 1 tested the increase of psychosocial health, measured as the change from pre- to post-test. Participants in the intervention group showed a high difference score for anxiety symptoms, and for QoL measured with the EORTC C30 and the WHO BREF, which encompass different aspects of QoL. Results for the measurement of the POMS did not show high DS for the IG. Notably, it only investigates the psychological aspect of QoL. Thus, in sum, digital art therapy seems to have a positive effect on the described aspects of psychosocial health. However, DS for depression increased for participants of the IG, whereas participants of the CG showed a decrease of the symptoms. These results are contradictory to our hypotheses and previous findings [5]. While causes remain to be determined, it is not unusual that in the course of coping with cancer the data can reflect a deeper emotional procession of grief and other negative feelings that may temporarily increase scores. This finding requires further investigation.

Hypothesis 2 focused on the changes in the three process measures from before to after each session. Descriptive values (n.s.) showed that participants experienced lower levels of distress and increased feelings of happiness after the two-hour sessions of art therapy. Further, the experience of beauty increased after every session and values stabilized over the eight weeks in the upper range (Sessions 5–8: M=5, on a scale from 0 to 6). A comparison of the experience of beauty in session one and session eight suggested an increase.

The acceptance of the therapy was high. In fact, it was so high that we could not compute the reliability because of a ceiling effect in the data. In other words, the lack of variance prevented reliability analysis, but indicated uniformly high acceptance. The feedback of the participants was positive throughout. Even if the analysis only explored the results in a descriptive manner, it suggests a strong approval of the different aspects of the therapy. The feedback of the participants indicated gratefulness for receiving art therapy and getting in touch with other women suffering from breast cancer. The therapy seemed to strengthen the sense of belonging, social connectedness, and provided a break from negative thoughts and feelings that often accompany the disease.

In sum, the descriptive results of the study indicate that the participants experienced an increase in their psychosocial health, both after the therapy sessions and after the eight weeks of intervention. The small sample size and limitations make these findings preliminary. Acceptance was very good and encourage implementation of the main study.

4.2 Limitations

The following limitations need to be considered for the interpretation of the results: The biggest limitation of the study was the small sample size. In a feasibility study, a small sample size is the usual case. In our case, the study is markedly underpowered, which makes the outcomes only valuable in terms of feasibility of their use. In our case, all of them can be used in the main study. Quantitative results of the analysis are preliminary, no evidence-argument can yet be made on their basis. The ceiling effect that prevented a reliability analysis of the acceptance scales, may alternatively also be explained by a response bias.

Details on limitations of the computations are: Moreover, the calculations of the process-measurements were limited, because not all patients attended all art therapy sessions, leading to missing values for Questionnaires C1 and C2. One of the six patients received chemotherapy every week before the art therapy. Sometimes, she could not attend the therapy session at all, or she reported being very tired or was late for the session. Personal issues of the patients outside of their disease might have also influenced the results. For example, one participant rated her psychosocial health as very bad for one session, because her husband had a stroke one day before. Many such variables remained uncontrolled in the CG, whose members may have had personal circumstances like medical setbacks or losses in similar ways as described for members of the IG, or may have participated in therapy-adjacent activities on their own and benefitted from them in the same way IG members benefitted from AT. It might be useful to build more information on these issues as well as adverse events into the full study.

A final limitation to be considered was an erroneous delivery of the post-measurement of Questionnaire B. The last page of the questionnaire had been missing in the sent-out version, and the remaining answers had to be collected via telephone and e-mail. Ten out of twelve participants answered the missing questions via phone or email. The results of QoL, measured by POMS, might be due to this alternative path of data collection. Thus, a comparison of the three QoL measurements has a limited scope. However, the EORTC-C30 and the WHO-BREF still seem to be more adequate for breast cancer patients; with their different QoL-subscales, they seemed to have worked better for the patients. The design was purposefully chosen this way, for gathering information on the feasibility of an RCT to follow. Even if the study framework did not allow a differentiated analysis of the questionnaires and reliable conclusions from quantitative outcomes, the study suggests a general feasibility and usefulness of the interventions and the scales employed.

4.3 Implications for future studies

The study has the practical implication that art therapists can be confident that online art-therapy is feasible and acceptable in a population of patients with breast cancer. Because of the small N we cannot derive policy implications. For future research, the study provides an impression of the potential obstacles to be considered in the main study, such as considering possible covariates (e.g., age) identified in the explorative MANOVA. To minimize these effects, researchers might consider matching future groups with respect to these covariates. Relying on the high acceptance found in this study, art therapy in oncological settings is potentially useful both, in-person and in online formats. Online therapy has the additional advantage of offering support of psychosocial health and well-being for breast cancer patients, without exposing them to the danger of an infection. In our study, it counteracted the social isolation of COVID-19 restrictions and allowed patients to get in touch among each other.

The current study contributes to the existing evidence of the acceptance of art therapy in oncological treatment. It provides valuable insights, particularly on the feasibility of the digital format of art therapy, and the acceptance of standard as well as art-therapy specific scales. In general, this study provides a basis for the use of online AT in quantitative studies, and ideas about the therapeutic factors of online AT. In comparison to face-to-face AT in the University Hospital Bonn, this form allowed German speaking patients independent of location to benefit from AT. Therefore, a continuation of online AT can add to the possibility of reaching a larger group of affected patients. Vulnerable populations are provided with high safety against viral contagions. Clinically, it has various social and participatory benefits, for example by reaching disadvantaged intersectional groups, such as mothers of small children living on the countryside, or older adults with motion impairments, who -- even in non-pandemic times -- could not come to a city hospital for two hours of art therapy. MANOVA is recommended as the statistical method in the main study. With a fully powered sample size, results of the analysis can be used to learn more about effects as well as the specific influences of covariates. We recommend that the full study includes a follow-up assessment to learn about sustainability of effects, and a qualitative assessment of the patients’ perception (e.g. using interviews or focus groups) to include the persons affected into studies with potential policy implications for their treatment.

5. Conclusions

The study adds value highlighting the potential contribution of art therapy on psychosocial health and acceptance of AT for patients during their oncological treatment. It contributes to closing a knowledge gap, because acceptance data on AT treatment was missing for the treatment phase as opposed to the rehabilitation phase. Moreover, it opens a new and future-oriented perspectives on AT in online settings. It demonstrated the feasibility and acceptance of the intervention, forming a basis for further implementation of AT in oncology.

An adequately powered RCT including moderation analysis, follow-up measures, and a qualitative assessment of the patients’ perspective can now follow to investigate the effectiveness of online AT. The study provides information for further evidence-based research in the field of art therapy in psycho-oncology. Creation is at the core of our human condition [16]. Supported by a professional art therapist, the oncology patient can discover and use the potential of art to counteract crises of meaning in an existential situation, experience health benefits and empowerment in creating one’s own narrative, and possibilities of re-gaining control.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Financial support

The project was funded by a grant of Bürgerstiftung Bonn for the study therapist, and by the participating institutions: The Research Institute of Creative Arts Therapies (RIArT), funded by the Software AG-Stiftung (Grant Number 9193), and the CIO – Center of Integrated Oncology, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany.

Data availability

The data is available through the corresponding author sabine.koch@alanus.edu.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the patients, our experience experts, for consistent participation in the study and providing us with inspiration through their feedback. We would further like to thank our institutions (CIO Bonn; and the RIArT at Alanus University, funded by the Software AG-Stiftung) for supportive structures around recruitment and implementation of the study, and PT (University of Maastricht) for dedicating her master’s thesis to the study. It was a meaningful process to work with the team on this feasibility study as part of our joint research activities.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained through the University of Bonn, Medical Faculty Ethics Board (484/20). Informed consent to participate and publish was obtained from all participants included in this study.

Authors’ contributions

The study is partly based on the Master Thesis of PT. SCK and DvR were thesis supervisors, and with the consent of the entire team SCK (Research Institute of Creative Arts Therapies, RIArT) drafted this publication. HG (RIArT) was the art therapy supervisor, KB was the study therapist. The study was conducted at the CIO – Center for Integrative Medicine, University Clinics Bonn, Bonn, Germany, under the supervision of ISW. MN, AK, VW, AF and RC (all CIO Bonn) were involved in recruitment, data collection, data organization, and data analysis. All authors were involved in turning the paper into its final version.

Author’s ORCID

References

[1] Archer S, Buxton S, Sheffield D. The effect of creative psychological interventions on psychological outcomes for adult cancer patients: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Psychooncology. 2015 Jan;24(1):1-10. DOI: 10.1002/pon.3607[2] Baker F, Denniston M, Zabora J, Polland A, Dudley WN. A POMS short form for cancer patients: psychometric and structural evaluation. Psychooncology. 2002;11(4):273-81. DOI: 10.1002/pon.564

[3] Bitsko MJ, Stern M, Dillon R, Russell EC, Laver J. Happiness and time perspective as potential mediators of quality of life and depression in adolescent cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(3):613-9. DOI: 10.1002/pbc.21337

[4] Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002 Feb;52(2):69-77. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3

[5] Bosman JT, Bood ZM, Scherer-Rath M, Dörr H, Christophe N, Sprangers MAG, van Laarhoven HWM. The effects of art therapy on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in adults with cancer: a systematic literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2021 May;29(5):2289-2298. DOI: 10.1007/s00520-020-05869-0

[6] Bradt J, Dileo C, Myers-Coffman K, Biondo J. Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Oct;10(10):CD006911. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006911.pub4

[7] Bradt J, Shim M, Goodill SW. Dance/movement therapy for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 7;1(1):CD007103. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007103.pub3

[8] Conrad I, Matschinger H, Reinhold K, Riedel-Heller S. WHOQOL-OLD und WHOQOL-BREF - Handbuch für die deutschsprachigen Versionen der WHO-Instrumente zur Erfassung der Lebensqualität im Alter. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2016. Available from: https://www.testzentrale.de/shop/handbuch-fuer-die-deutschsprachigen-versionen-der-who-instrumente-zur-erfassung-der-lebensqualitaet-im-alter.html

[9] Czamanski-Cohen J PhD, Wiley JF PhD, Sela N BA, Caspi O MD, PhD, Weihs K MD. The role of emotional processing in art therapy (REPAT) for breast cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(5):586-598. DOI: 10.1080/07347332.2019.1590491

[10] de Witte M, Orkibi H, Zarate R, Karkou V, Sajnani N, Malhotra B, Ho RTH, Kaimal G, Baker FA, Koch SC. From Therapeutic Factors to Mechanisms of Change in the Creative Arts Therapies: A Scoping Review. Front Psychol. 2021 Jul 15;12:678397. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678397

[11] Dóro CA, Neto JZ, Cunha R, Dóro MP. Music therapy improves the mood of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cells transplantation (controlled randomized study). Support Care Cancer. 2017 Mar;25(3):1013-1018. DOI: 10.1007/s00520-016-3529-z

[12] Fancourt D, Finn S. What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? (Synthesis Report 67). Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019.

[13] Frankl VE. The will to meaning: Foundations and applications of logotherapy. New York: Penguin; 1988.

[14] Geue K, Richter R, Buttstädt M, Brähler E, Singer S. An art therapy intervention for cancer patients in the ambulant aftercare - results from a non-randomised controlled study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2013 May;22(3):345-52. DOI: 10.1111/ecc.12037

[15] Gruber H. Art therapy in oncology and palliative care - overview of empirical results and a case vignette. Rehabil Sci Nurs Physiother Ergother. 2019;5-16. DOI: 10.33607/rmske.v2i19.756

[16] Gruber H, Hertrampf R, Koch SC. Kunst-, Musik-, Tanztherapie in der Psychoonkologie. Psychother Dialog. 2023;24:64-8. DOI: 10.1055/a-1817-8817

[17] Grulke N, Bailer H, Kächele H, Bunjes D. Psychological distress of patients undergoing intensified conditioning with radioimmunotherapy prior to allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005 Jun;35(11):1107-11. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704971

[18] Havsteen-Franklin D, Tjasink M, Kottler JW, Grant C, Kumari V. Arts-Based Interventions for Professionals in Caring Roles During and After Crisis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front Psychol. 2020;11:589744. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.589744

[19] Hermann C, Buss U, Snaith R. HADS-D - Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - Deutsche Version: Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung von Angst und Depressivität in der somatischen Medizin, Testdokumentation und Handanweisung. Bern: Huber; 1995.

[20] Herrmann C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale--a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997 Jan;42(1):17-41. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00216-4

[21] Ho RTH, Fong TCT, Cheung IK, Yip PSF, Luk MY. Effects of a short-term dance movement therapy program on symptoms and stress in patients with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(5):824-31. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.332

[22] Ho RTH, Fong TCT, Yip PSF. Perceived stress moderates the effects of a randomized trial of dance movement therapy on diurnal cortisol slopes in breast cancer patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018 Jan;87:119-126. DOI: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.10.012

[23] Hutter N, Vogel B, Alexander T, Baumeister H, Helmes A, Bengel J. Are depression and anxiety determinants or indicators of quality of life in breast cancer patients? Psychol Health Med. 2013;18(4):412-19. DOI: 10.1080/13548506.2012.736624

[24] Kaimal G, Mensinger JL, Drass JM, Dieterich-Hartwell RM. Art therapist-facilitated open studio versus coloring: differences in outcomes of affect, stress, creative agency, and self-efficacy. Can Art Ther Assoc J. 2017;30(2):56-68. DOI: 10.1080/08322473.2017.1375827

[25] Kazdin AE. Annual Research Review: Expanding mental health services through novel models of intervention delivery. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019 Apr;60(4):455-472. DOI: 10.1111/jcpp.12937

[26] Koch SC. “Being moved” as a therapeutic factor of dance movement therapy. In: Chaiklin S, Wengrower H, editors. Dance and creativity within dance movement therapy: international perspectives. 1st ed. New York: Routledge; 2021. p. 96-111. DOI: 10.4324/9780429442308-10

[27] Koch SC. Arts and health: active factors and a theory framework of embodied aesthetics. Arts Psychother. 2017;54:85-91. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2017.02.002.

[28] Koch SC, Mergheim K, Raeke J, Machado CB, Riegner E, Nolden J, et al. The embodied self in Parkinson's disease: feasibility of a single tango intervention for assessing changes in psychological health outcomes and aesthetic experience. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:287. DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00287

[29] Kortum R, Koch SC, Gruber H, Radbruch L. Kunsttherapie in der Palliativversorgung: ein narratives Review II: Anwendungen. J Integr Med (Ger). 2018;10(1):42-50. DOI: 10.1055/s-0044-100059

[30] Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF). Evidenztabellen S3-Leitlinie Psychoonkologie, 2.0, AWMF-Registernummer 032-051OL. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 28]. Available from: https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/psychoonkologie/

[31] Lim HA, Mahendran R, Chua J, Peh CX, Lim SE, Kua EH. The Distress Thermometer as an ultra-short screening tool: a first validation study for mixed-cancer outpatients in Singapore. Compr Psychiatry. 2014 May;55(4):1055-62. DOI: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.01.008

[32] McNair D, Lorr M, Doppleman L. POMS manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1971.

[33] Mehnert A, Müller D, Lehmann C, Koch U. Die deutsche Version des NCCN Distress-Thermometers. Z Psychiatr Psychol Psychother. 2006;54(3):213-23. DOI: 10.1024/1661-4747.54.3.213

[34] Mental Health Foundation. Coronavirus: The divergence of mental health experiences during the pandemic. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide

[35] Michels FA, Latorre Mdo R, Maciel Mdo S. Validity, reliability and understanding of the EORTC-C30 and EORTC-BR23, quality of life questionnaires specific for breast cancer. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2013 Jun;16(2):352-63. DOI: 10.1590/S1415-790X2013000200011

[36] Nolte S, Liegl G, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, Costantini A, Fayers PM, et al. General population normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 health-related quality of life questionnaire based on 15,386 persons across 13 European countries, Canada and the United States. Eur J Cancer. 2019;107:153-63. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.11.023

[37] Odunlade A, Rawcliffe D, Acott K, Rioga M, Mosoeunyane M, Kemp R, Murdoch C, Sines D, Doran R. Living with Fear: Reflections on COVID-19. Independent Publishing Network; 2020. p. 224.

[38] Öster I, Tavelin B, Egberg Thyme K, Magnusson E, Isaksson U, Lindh J, Åström S. Art therapy during radiotherapy: a five-year follow-up study with women diagnosed with breast cancer. Arts Psychother. 2014;41(1):36-40. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2013.10.003

[39] Petersen P, Gruber H, Tüpker R, editors. Forschungsmethoden künstlerischer Therapien. Wiesbaden: Reichert; 2011. p. 372. DOI: 10.29091/9783752001228

[40] Radl D, Vita M, Gerber N, Gracely EJ, Bradt J. The effects of Self-Book art therapy on cancer-related distress in female cancer patients during active treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2018 Sep;27(9):2087-2095. DOI: 10.1002/pon.4758

[41] Romito F, Lagattolla F, Costanzo C, Giotta F, Mattioli V. Music therapy and emotional expression during chemotherapy: how do breast cancer patients feel? Eur J Integr Med. 2013;5(5):438-42. DOI: 10.1016/j.eujim.2013.04.001.

[42] SoSci Survey GmbH. SoSci Survey (Version 3.1.06). Available from: https://www.soscisurvey.de

[43] Tang LL, Zhang YN, Pang Y, Zhang HW, Song LL. Validation and reliability of distress thermometer in chinese cancer patients. Chin J Cancer Res. 2011 Mar;23(1):54-8. DOI: 10.1007/s11670-011-0054-y

[44] The WHOQOL Group. Development of the WHOQOL: rationale and current status. Int J Ment Health. 1994;23(3):24-56. DOI: 10.1080/00207411.1994.11449286

[45] The WHOQOL Group. The development of the World Health Organization quality of life assessment instrument (the WHOQOL). In: Orley J, Kuyken W, editors. Quality of life assessment: Wang Y, Duan Z, Ma Z, Mao Y, Li X, Wilson A, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems among patients with cancer during COVID-19 pandemic. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):1-10. DOI: 10.1038/s41398-020-00950-y

[46] Wang Y, Duan Z, Ma Z, Mao Y, Li X, Wilson A, Qin H, Ou J, Peng K, Zhou F, Li C, Liu Z, Chen R. Epidemiology of mental health problems among patients with cancer during COVID-19 pandemic. Transl Psychiatry. 2020 Jul 31;10(1):263. DOI: 10.1038/s41398-020-00950-y

[47] World Health Organization. Breast cancer: fact sheet. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer

[48] ZfKD. Krebsdaten: Breast cancer, ICD-10 C50. 2023 Dec 23 [cited 2023 Aug 28]. Available from: https://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/EN/Content/Cancer_sites/Breast_cancer/breast_cancer_node.html