The phenomenon of love in the therapeutic relationship: an autoethnographic case study

Parnian Dehesht 11 SRH Hochschule Heidelberg, Heidelberg,Germany

Abstract

Objective: In this autoethnographic case study, I set out to explore the phenomenon of love in the therapeutic relationship – a subject that has long been acknowledged as a central, yet underexplored, element in clinical practice. Recognizing love as one of the most intense human experiences, I believe that its presence in therapy – whether experienced as an observer, an object of affection, or an active participant – holds significant implications for both client outcomes and therapist self-awareness. In this study, I aimed to investigate how love emerges during music therapy sessions with Lila, a fifteen-year-old girl with severe cognitive and physical disabilities, and to understand its impact on the therapeutic process, including both its potential benefits and risks.

Methods: I conducted twelve 30-minute music therapy sessions with Lila. To capture the subtle interplay of personal emotions, countertransference, and the dynamics of our therapeutic interaction, I engaged in reflexive writing and maintained a detailed diary both before and after each session. This autoethnographic approach allowed me to document and analyze my internal experiences alongside the observed therapeutic processes.

Results: My autoethnographic analysis revealed that adopting a loving stance in therapy deepens empathy, fosters a more attuned connection, and enhances the overall therapeutic presence. However, I also observed potential risks, such as blurred boundaries and increased personal vulnerability, which complicate the therapeutic relationship and demand careful navigation.

Conclusion: I conclude that the decision to integrate love into therapeutic practice must be highly individualized, requiring careful ethical and relational consideration. My findings contribute to a broader understanding of love’s multifaceted role in therapy and underscore the need for further exploration of its clinical, cultural, and psychological dimensions.

Keywords

love, therapeutic relationship, music therapy, counter-transference, non-verbal communication

1 Introduction

1.1 Why should we still study love?

This question occurred to me when I found a favorite child after several months of working as a music therapist intern in a care center for children with severe disabilities. I would think about him several times during the day, meet him before anyone else when I was at the center, and put myself all out for his sessions to be perfect. His level of engagement with me was also drastically increasing, as he was using his voice, his arms, and his legs to make music with me and generously showing that he was enjoying it. This special relationship did not strike me as a topic of research until he got hospitalized for an infection and I faced the disappointment that followed, and until I felt ashamed when my colleagues saw my disappointment.

I was a music therapist in training, and I was, to the best of my knowledge, loving this little child. Yet, love had never had a place in my professional life.

Do I resist it, deny it, get over it, or do I embrace it, enforce it, and spread it?

Should I make sure that I do not feel as strongly for another child, or should I open my mind to the possibility of loving more of them? Do I want a passive role about how I feel about every client, or do I want to pursue an active one?

What made me love this child and not any other one, and what does this love do to our therapeutic relationship? What does it do to the music that we make, and to our non-verbal communication?

I did not know the answer to any of these questions, but I had surely learned during my studies to embrace the questions regardless of the answers.

I started this study by giving an overview of love in psychological literature: the meaning of love, different approaches to categorizing it, its effect on human development, and its presence in a therapeutic relationship.

I included some of the most common definitions and categorizations of love in literature as far as they aligned with the therapeutic scope of this article, such as the ancient stories that shape our primary ideas about love, and the different qualities of love towards different objects (a child, a mother, a friend, a lover). I also used the most highly regarded and representative literature in developmental psychology to study the effect of love on psychological structures. As in consensus with the guidelines of a therapeutic relationship, I have excluded the common areas of sex and love from this study.

In parallel to my search in literature, I did a case study with a child with severe cognitive and physical disabilities to investigate the appearance of love in a therapeutic relationship. Due to the nature of my topic and the non-verbal relationship with my case, I chose an autoethnographic methodology to gather data and analyze it.

As a final remark in this introduction, I chose to use the term “children with disabilities” to refer to this population as it was the most recommended term from within the community [1].

1.2 An Overview of literature

1.2.1 What is love?

The question of love has been addressed throughout history by myriads of approaches and attitudes. Poets, artists, scientists, and practitioners of religion have different answers to this question. In therapy, we often explore the concepts of self-love, falling in love, and feeling loved. We also talk about loving a certain session, loving a piece of music, loving the time spent with a group, and loving the client. Love, as Freud said, is “employed in language in an undifferentiated way”. However, the appearance of love in a therapeutic relationship is still a topic that many scholars shy away from. To realize how love is relevant to the therapeutic setting, we need to first employ the word in our language in a differentiated way [2].

The origin of the word love goes back to the Sanskrit Lubhyati which means he desires, and it shares a common root with libido. This desire plays an underlying role in all different meanings of the word [3], [4]. The transitive verb “to love” is invested in an object [5]. Therefore, it is safe to assume that for a human to love is, at a basic level, for a human to desire an object. But apart from an old Sanskrit word and a verb, what is love and what does it do to us?

Many scholars define love as an attitude, many categorize it as an emotion [6]. Following Leighton (1959), some scholars believe that love is both and is therefore classified as a sentiment:

In a quest to explain the neural mechanisms of expression of love and its deprivation, R. Komisaruk and Whipple (1998) defined love as one’s having the sensory stimulation that one desires:

This stance can be of therapeutic value, explaining how the deprivation of such yearned-for stimulation can propel the body to provide a substitute for the stimulation. With chronic deprivation, this effort may become frozen into a compulsive behavior or psychosomatic symptoms, as in a conversion reaction [3]. In psychoanalytic theory, using repression as a defense mechanism is a precondition for the emergence of conversion symptoms [7].

Such studies on early infancy and childhood give us a good image of the importance of a secure early attachment with the primary caregiver and the consequences of its deprivation (Bowlby, 1988; Stern, 1985). We might go as far as believing that being loved has an evolutionary role for the child and its deprivation can cause serious physical and mental issues.

Arguing which word explains the concept of love better is beyond the scope of this study. Therefore, it is for the reader to decide what love is for them – an emotion, an attitude, a sentiment, or a sensory stimulation. But one thing is for sure, that love does not mean the same thing for everybody. In the next chapter, I will go through the common categorizations of love.

1.2.2 Taxonomy of love

No matter how we define love, as in everyday life, many different types of it manifest in therapy, including the love of parents and child, romantic love, sexual love, and the love among friends [8]. Are they all the same thing with different objects of interest, or do these kinds of love differ on a more fundamental level? Being familiar with the categorizations of love might help us find a clearer stance toward its presence in a therapeutic relationship. In this chapter, I review the common systems that categorize love.

The ancient fictions

As cited in Lasswell and Lasswell (1976), after extensive research on the fictional and non-fictional literature of love, Lee (1974) introduced the six typologies of love [5], [8]

Storge (life-long friends): this type of love is characterized by mutuality, interdependency, and rapport. It is in many ways similar to the type of love shared among siblings [5].

Agapic (other-centered): this type of love is characterized by forgiveness and patience. The agapic lovers do not “fall in love”. The love that they have for others is always available and their love objects simply allow them to show it to a greater extent [5]. This kind of love resembles the love of parents for their children in nature.

Mania (possessive and intense dependency): Characterized by anxiety, jealousy, and possessiveness, this kind of love brings a lot of highs and lows in the dynamic of a relationship [5].

Pragma (logical-sensible): pragmatic love is based on realistic and well-thought calculations. It is committed, steady, and has planned prospects [5]. This type of love might be recognized in long-term and arranged marriages.

Ludus (self-centered game player): the ludic lovers fear commitment and dependency. It mostly revolves around the fulfillment of one’s own needs without great self-revelation from either side [5].

Eros (romantic): this type of love is characterized by idealizing the other person and wanting to share “everything” with them [5].

These are the constructed ideal types of differentiating between conceptions of love and the authors believe that each loving relationship can incorporate some degree of many of these conceptions [5], [9].

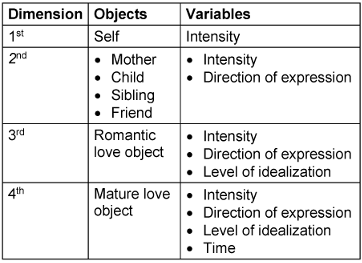

The psychological view

According to Berscheid (2009), it was not until the middle of the twentieth century that psychologists started attempting to comprehend love. Since then, we are coming to understand how important love is to understanding relationship phenomena and how little is known about it. Berscheid (2009) has also given a comprehensive overview of the timeline of the psychological studies on love which is beyond the scope of this study. As a representation of psychological studies, I have summarized Solomon’s (1959) system of categorization of love in Table 1 [Tab. 1] [6], [4].

Love in the first dimension

Self-love: The basis of all love may be the primitive instinct – the life force. As the location of this force is always in the self, this kind of love is one-dimensional, varying only in intensity. Serious physical or mental illnesses can lead to the disappearance of this force which can further result in physical or mental death [4].

Love in the second dimension

Love for the mother: This form of love appears when the self is unconsciously projected elsewhere and loved. As in love for the mother, a child, a sibling, or a friend. The newborn babies most likely believe their mother is a part of them. They want her back immediately after they realize that the mother can leave them as for them, it appears to be the closest thing to being wonderfully safe and whole again. The feeling of protection extends to other protective figures as the youngsters get older. Losing a mother can lead to emotions of utter desolation and abandonment, especially in people without a higher type of love investment, leading the children to believe that they are about to die [4].

Love for the child: Just like the desire to be with the mother, the desire to be with the child can also be seen in many lower animals, particularly mammals. However, most of what one sees in nature can be based on protective patterns. In humans, the relationship persists even after the maturation of the young when their survival no longer depends on that relationship [4].

Love for a sibling/friend: The feelings towards siblings or friends can be mixed: seeking protection and comfort, providing support, rivalry, jealousy, and finally partial identification, and sharing. It is recognizable by its platonic features [4].

The two dimensions of projected self-love are the intensity of the feeling and the direction of expression or projection [4].

Love in the third dimension

Romantic love: Adding a variety of idealness to the equation, one can experience romantic love. Which is to see the ideal version of oneself in the eyes of another, who is reciprocally idealized in one’s own eyes. This cross-identification results in infatuation, which is the basis of romantic love. The level of symbolization and abstraction that is involved in this process is different from the previously described forms of love. The third dimension of this kind of love is what might be, as distinguished from what is. The characteristic mode of expression in romantic love is sexual and can be described as love for what one should like to be [4].

Love in the fourth dimension

Mature love: Four-dimensional love is mature love that strives toward an eventual ideal. As the over-evaluation of the ideal partner dissolves in confrontation with reality, there remains a disillusioned and grim couple, who are not necessarily defeated. All the previously described sorts of love still may be present to some extent in the relationship as the partners switch roles between the parent, the child, the friend, and the lover. The patience, tolerance, and flexibility of the couple and their willingness to be thankful for whatever is still left determine the future of the relationship; and of course, their self-love. When the couple realizes that there is no perfection, but they can fulfill themselves and their collective potential together, the relationship transcends the here and now and involves the future. This kind of love, therefore, involves four dimensions: intensity, projection, idealness, and time [4].

1.2.3 To be or not to be loved

In this chapter, I present the literature on the psychology of attachment and development to explain the possible role of love in these processes and the possible outcome of its deprivation.

A Secure base

Together with Harlow (1959), Bowlby (1982) rejected the Pavlovian behavioral frameworks that saw emotional ties as incidental results of feeding. Instead, he believed that human infants were innately relational, predisposed to what Harlow termed “contact comfort”, and prone to seek out the company of consoling individuals when in need. Based on this, Bowlby hypothesized that the development of an infant’s emotional bond with their primary caregiver depends on the infant's propensity for seeking proximity, the caregiver's receptivity to the infant's bids for proximity, and the caregiver's capacity to offer safety and comfort when necessary. He specifically emphasized the importance of the ability of the caregiver to provide a “secure base” for the infant [10], [11].

Eye contact, holding, touching, caressing, smiling, crying, clinging, a desire to be comforted by the relationship partner when upset, the experience of anger, anxiety, and sorrow following separation or loss, and the experience of happiness and joy upon reunion are all characteristics of love in both infancy and adulthood. Furthermore, the development of a stable relationship with either a main caregiver or a romantic partner depends on the sensitivity and responsiveness of the caregiver or partner to the closeness bids of the increasingly attached person. The attached person becomes happier, more outgoing, more confident, and more compassionate as a result of this responsiveness [11], [12].

Attachment and caregiving

Bowlby (1982) introduced three innate behavioral systems that Shaver and colleagues later incorporated to develop a “Behavioral Systems Approach to Romantic Love Relationships: Attachment, Caregiving, and Sex” [12], [13].

The effect of deprivation of love is probably best studied in situations of lack of parental love. As discussed earlier in this chapter, the sentiment of love in parents brings evolutionary benefits to children. One can assume that loved children are more likely to be physically protected, emotionally held, handled with empathy, and experience attunement with their caregivers.

According to the behavioral systems approach, the deprivation of love equals the deprivation of a secure attachment and proper caregiving. When an individual's attachment figures are not consistently present and encouraging, a sense of attachment security is not achieved, and the distress that initially activated the system is exacerbated by serious doubts and fears about the likelihood of achieving a sense of security: “Is the world a safe place or not?”

The attachment system appears within the first two years of life. Therefore, the other two systems (caregiving and sex, which emerge later in development) may be impacted by the attachment system’s pattern of functioning and particular kinds of dysfunction, such as hyperactivation or inactivation [11], [13].

Insufficient attachment and caregiving can lead the child to create a negative sense of self. This negative view of self can have protective functions. According to Shapiro and Rosenfeld (1987), if the child is the bad one, they can protect the image of the parent as good, and with that, they live in a world that is good or just. Living in an evil world is intolerable for children. Secondly, if it is the child's badness that caused the abuse, the child can retain the hope, unrealistic as it may be in these situations, that if they behave better, life will improve. This hope, rather than the grim reality of life, helps the child to continue living [7].

Experience of the self

One of the most potent social sensations is the feeling that we truly are with the person we are interacting with. In addition, the sensation of being with someone who is physically not there can be just as strong. Absent people can be perceived as either tangible presences or silent abstractions that are only barely recognized. The example of falling in love is typical. The focus of lovers extends beyond simple preoccupation. The loved one is frequently perceived as a constant presence, sometimes even as an aura, that influences practically everything a person does, whether it be altering how they perceive the world or reshaping and perfecting their very movements. In this view, being with the other is viewed as an active attempt at integration rather than a passive failure of differentiation. The infant can interact with another person in such a way that the two combine their activities to produce an effect that would not be possible without the blending of their behaviors. [14].

During the sensitive developmental processes according to D. Stern (1985), the child develops four interrelated senses of self: the emergent self, the core self, the subjective self, and the verbal self [14](11). The presence and assistance of a “good enough” caregiver are essential to the child’s ability to integrate and organize their experience of the world (the emergent self), generalize these experiences to get a sense of self and distinction from other objects in their environment, form the first attachments, regulate their emotions (the core self), realize the gap between their subjective reality and that of the others, and how and to what extent to bridge this gap (the subjective self). An empathic caregiver can also hold the child as they learn the language as the new medium of creating and exchanging meaning (the verbal self) and tackle the challenges that arise in the way of integrating self-experiences and self-with-the-other-experiences through this medium [14].

Building on these theoretical considerations, the present study focuses on the phenomenon of love in the therapeutic relationship. If early experiences of being held in love shape the foundation for secure relating to oneself and others, it becomes essential to explore how love is experienced and enacted within therapeutic contexts, where processes of healing, growth, and transformation occur.

By investigating this phenomenon through an autoethnographic case study, the aim is to situate personal experience within a broader theoretical and clinical discourse, thereby contributing to a more nuanced understanding of how love functions as a relational and therapeutic factor.

2 Methods

2.1 What is an autoethnographic case study?

My research question crystallized after seven months of working with children with severe cognitive and physical disabilities. I noticed that I see better outcomes with children that I specifically like (or if I dare say, love). I was not sure what had happened first, me liking them or them interacting with me. As mentioned in the introduction, my muse for this research topic was specifically a five-year-old boy with whom I was seeing remarkable potential in music therapy. Needless to say, I could not assign children to two groups (one to love and one not to love) and measure the outcomes of music therapy. To study this topic, I needed a methodology that delicately moves with my natural process and structures it.

After a long time of studying different methodologies and according to the nature of my topic, I found an autoethnographic methodology to be the best fit for my research questions.

Autoethnography is the method of incorporating subjective experience (auto) into a systematic analysis (graphy) of a sociocultural experience (ethno) [15]. As a method based on the experience of the researcher, it enables an approach to the phenomena that are difficult to grasp with other methods of qualitative psychology (interviews, observations, etc.). This applies, in particular, to emotionally charged topics such as love, grief, or joy; but also body-related topics such as disability, sexuality, or illness [15].

According to Choi (2016), the goal of participating in autoethnographic spaces is to establish methods for properly addressing the abundance of experiences, desires, social and political contexts, and ideologies that are specific to the standing point of each researcher. These are incredibly unique settings where researchers draw on the theoretical underpinnings of autoethnographic perspectives while also moving with their data, analysis, and interpretations, informed by both their research experience and their own “insight, intuition, and impressions” [16].

Unlike an autobiography which often examines a person’s whole life history, an autoethnography is typically focused on the lived experiences that pertain to the topic under inquiry. This is a key differentiation to be made in terms of using “life history” in this context. But unlike other ethnographers, autoethnographers benefit from instant access to a wider pool of data, especially when it comes to being able to access memories that can delve deeper into the layers of the phenomena under study [17].

My interest in doing autoethnography research was mainly evoked by reading “Creating a multivocal self” by Julie Choi [17]. Similar to Choi’s journey of finding her multivocal identity as a multilingual person, I am also restructuring my many selves that exist in different languages, especially the language of music that facilitates my non-verbal communication with children with disabilities. Even though the contact surface that I have with these children does not directly include my experiences outside of the music therapy room, my outside experiences affect me as a person, and what I am as a person affects what I offer as a music therapist. Understanding how love affects me, my client, and our therapeutic relationship is a work in progress, and I follow Choi in my intention to signify the importance of working in the middle of things as a necessary process to understand the phenomenon of love in a therapeutic relationship:

I use the term “contact surface” to remind myself that what appears in the therapeutic setting is not all that there is. Particularly in working with children with disabilities, it is a challenge to learn that silence does not mean emptiness. And even though the contact surface might appear stagnant, there could be a lot of internal processes going on here and now. This encouraged me to pay attention to what could be beneath the contact surface, both from my side and theirs. In psychoanalytical terminology, this could translate as studying transferences and counter-transferences. This guided me over and over again to rely on my three “I”s: “insight, intuition, and impressions” [18]. Therefore, I found an autoethnographic case study to be a suitable methodology for me to study what happens in the deeper layers of a therapeutic encounter.

2.2 Studying two minds simultaneously: empathy

My case study is inevitably a study of two cases: my client and me. As I closely observe my client for any movement, sound, and mood, I also draw on my own internal resources “insight, intuition, impression” as data. This dynamic signified the importance of clearing my mind from my strong ideas, thoughts, and concerns to be better able to approach reality in my interpretations and to suspend my judgments to be fully present. This empathic approach is already beautifully explained by Carl Rogers in A Way of Being [19]. In this case study, I tried to actively push the borders of my empathy further and practice it before and after each session. I will describe the steps in the next section.

On my way to understanding the kind of empathic research that I want to do, reading Participatory Mind, a book written by Henryk Skolimowski in 1994 came as a source of inspiration [20].

According to Skolimowski [20], “what clinical detachment is for objective methodology, empathy is for the methodology of participation. And all therapy is an attempt to bring the person back to meaningful forms of participation” (p. 182).

Inspired by this theory that empathy gives us a new sensitivity to dwell in the other’s life, I spent at least thirty minutes before each session to do free association, reflexive writing, and in his words, prepare my consciousness and meditate on the form of being of the other. I used these notes as data to report on my struggles with the phenomenon of love and the counter-transferences that appeared. In that regard, my autoethnographic work could be categorized as reflexive autoethnography [15].

2.3 Diary as data

I write because I want to find something out. I write in order to learn something that I didn’t know before I wrote it… How we are expected to write affects what we can write about… Writing is validated as a method of knowing [17].

To study me, my client, and our relationship during this study, I incorporated three-layered journaling after each session to report

- how I immediately and more objectively perceived the session,

- how I think my client perceived the session, and

- how I subjectively perceived the session, incorporating my associations, feelings, and when necessary, life history.

This is an alteration of a method previously used by Forinash and Gonzalez in A Phenomenological Perspective of Music Therapy [21]S. I also used my aforementioned notes during the thirty minutes of free association.

To encourage the free flow of data, I used a freestyle digital pad that does not show the count of words or pages so that I could keep writing without having a sense of “enough”. I also did not plan to publish my raw diary to minimize self-censoring.

I also video-recorded the sessions without having a clear intention to use them. Analyzing the video and the sound of the sessions is beyond the scope of this study and might be done later.

2.4 The natural process as an intervention

My intention to study love required bringing a new sensitivity to study the natural course of therapy. Therefore, I chose not to change anything about my normal interventions; but rather, gather data from the routine practice that I was already doing with a new sensitivity. This meant doing thirty minutes of music therapy twice a week. Primed by thirty minutes of free association and followed by thirty minutes of journaling.

The only thing that I changed in my routine as a music therapy intern was the choice of my case. In consultation with my supervisor, I was advised to work with a child that I didn’t already have contact with. Given the fact that during the seven months of my internship, I had already worked with all the children that I liked, this meant that I had to walk out of my comfort zone and work with the children that I found more difficult to work with.

To add a sense of randomization in choosing the subject of my case study, I sent a request to record music therapy sessions to the official guardians of the children with whom I had not established contact before, aiming to work with the first recording permission that appeared. Therefore, my decision to start this case study with Lila was random, following a primary inclusion criterion of not having a prior bond.

2.5 Music as a mediator

During my work as an intern, I collected a couple of music therapy methods in my toolbox which I intuitively drew from during this study:

Music-based communication

Thanks to my supervisor, I was introduced to this method and trained for it during my internship. The concept of music-based communication wants to show ways of using the musical accessibility of people with complex disabilities not only for listening to music but above all for communication. This can be done using improvised music that is based on the movements, sounds, or breathing of the other person. These bodily expressions contain musical elements such as tones, tempo, rhythm or intensity, and volume. In this way, musical-motoric dialogues are created, with which one can communicate moods and feelings [22].

Nordoff-Robbins approach

Music-based communication borrows some technics from the Nordoff-Robbins approach to music therapy, which is based on the belief that everyone possesses a sensitivity to music that can be utilized for personal growth and development. In this form of treatment, clients take an active role in creating music together with their therapists. Through this interaction, therapists support and enhance the clients' expressive skills and their ability to relate to others [23].

Perhaps I am waiting for some moment of transmission, or for some appropriate wave – or should it be waves – of the unseen to lap upon the shore of possibility. In the meantime, I am overwhelmingly grateful that there is so much to be done, to be learned, discovered, celebrated, shared, and that an infinite ocean of creation and love awaits release [23].

Authentic singing

During the process, I was intuitively drawn to using my voice instead of other instruments. And the surprising reaction of the children to my voice made me use it more and research it. In my attempt to understand the power of voice, I encountered the inspirational book Authentic Voices, Authentic Singing: A Multicultural Approach to Vocal Music Therapy by Sylka Uhlig, who was also an inspirational professor during my studies [24].

Without realizing it, I was using primitive melodies in my music therapy sessions which was positively reinforced by the children’s reaction to it. Uhlig emphasizes the power of these melodies to soothe us just like many of us were soothed as infants by a warm female voice [24]. According to [24](34), “a constantly repeated and varied motif is all that constitutes a primitive melody. Also, the voice timbre and emotionality have a stronger connection to the meaning than the melody's compositional structure does” (p. 50).

Without a surprise, this quality of voice brought me the associations and counter-transferences of a motherly figure during my case study, which combined with the focus on the phenomenon of love, activated strong internal processes.

Voice is known to be the most personal and intimate instrument that we possess. When we vocalize, the body is our instrument. The body has been treated in different ways by us and others. How our bodies have been handled with care and love, or with rigidity, violence, or abuse has been saved in our minds and bodies as memories. Memories that we can listen to in a person’s voice [24].

The strong therapeutic potential of the use of voice, how it seems like a physical act but activates deep psychological processes, how it seems personal but roots back to cultural influences, how it expresses the self and mediates a connection, “and how it can channel eros while Thanatos seems to hold away in the psyche” is well described by Uhlig in her book [24].

2.6 Plan

I planned to meet Lila twice a week for six weeks, each session lasting for 90 minutes: 30 minutes of reflexive writing, 30 minutes of music therapy, followed by 30 minutes of journaling. During the music therapy session, I would do a quick assessment at the beginning of the session and decide which instrument to use, always starting with accompanying her breathing with a pianissimo sound, observing her reaction, and adjusting the sound accordingly.

2.7 Autoethnographic analysis

I followed Chang’s strategies from the book Autoethnography as Method in my data analysis. The order of steps and their description is taken from his book [25]. I have also explained how I implemented these steps in my research below.

Search for recurring topics

Chang (2008) recommends that the researchers search for recurrence in their data to identify the core elements of their experience. I have included these recurrent themes at the end of each chapter in the results section with pound (#) signs.

Look for cultural themes

A cultural theme is a premise or stance that is either explicitly stated or implicitly accepted by a culture and generally controls behavior or stimulates activities. These themes can explain the connection between different elements of the data. According to Chang (2008), searching for these cultural themes is a crucial last step in autoethnographic research.

Identify exceptional occurrences

Although patterns and routines can reveal a lot about our lives, not all elements of our lives adhere to them. Extraordinary occurrences and interactions frequently alter the direction and have a significant influence on life. Opening eyes to new viewpoints, cultural norms, people, and places is a common result of first-time cross-cultural encounters. People seldom revert to their former selves after having a life-altering experience; instead, they tend to advance in a new path. Determining extraordinary events in life may therefore be quite helpful in learning about oneself. According to Chang (2008), data analysis and interpretation can be organized around these life’s unusual circumstances.

In my study, I actively searched for moments of surprise and unfamiliarity and included them in the results section.

Analyze inclusion and omission

Data interpretation and analysis often focus on what is included in the data set, namely what is gathered and what the obtained data mean. But we shouldn’t forget that the data also benefit from the information that is left out. There are several causes for the lack of data. On the one hand, certain aspects of life are just absent, therefore there is nothing to record in data. On the other side, data omission might occur when they are purposefully or unintentionally left out of a recording. Asking a question regarding omission for each inclusion is one method of identifying omission in data (35). “Omission in data reveals an autoethnographer’s unfamiliarity, ignorance, dislike, disfavor, dissociation, or devaluation of certain phenomena in life. Above all, it may illuminate what is valued and devalued in the society” [25].

In the last chapter, I reflect on what I could have seen but chose not to see. Or what I could have done and chose not to do.

Connect the present with the past

Autoethnographers can learn how their current beliefs and behaviors are influenced by historical events using this history-conscious approach. Even while researchers may wish to draw a direct link between the past and the present, the apparent cause-effect relationship is never proven with confidence when using this technique. The ability to explain the relationship between the present and the past requires logical thinking, creative thinking, and intuition as there are no “scientific” instruments available to establish correlation. Although approximate, this relationship is a viable choice for autoethnographic investigation and interpretation [25].

During my reflection session, I had strong associations with my life memories. Some of which turned out to be surprisingly revealing about the roots of my behavioral patterns. I have mentioned these correlations in the results section.

Analyze relationships between self and others

Chang (2008) suggests identifying others of similarity and others of differences in data analysis.

[Others of similarity] includes those who belong to the same community of practice, share common identities, and/or identify with each other. During data analysis and interpretation, you can ask yourself questions such as “Who are my others of similarity?” “What binds us together?” “What forms the foundation of my bonding with these others of similarity?” In addition to others of similarity, you can also look for others of difference in your life. The others of difference represent communities of practices, sets of values, and identities different from yours or unfamiliar to you. These others often help you see yourself more clearly by contrast. In some occasions you may consider merely different, others irreconcilably oppositional [25].

I used this step to reflect on what makes it easier for me to work with some children and not with others. I have also reflected on the others that have drawn or repelled me during my literature search.

Compare cases

Comparing two different examples might help us see the similarities and contrasts between them. Different persons, occasions, or circumstances can be inferred from the data in autoethnographic research. Our awareness of “difference and commonality” and our growing self-awareness are both enhanced by the comparison technique [25].

I incorporated this step to compare different sessions and how my attitudes, expectations, and moods might have affected them.

Contextualize broadly

I have contextualized my results to the extent that would fit the lens of a therapeutic relationship. I have deliberately excluded geopolitical and economic aspects of my experience.

Compare with social science constructs

This step covers my choice of methodology with a societal critical view.

Frame with theory

Finally, I have used the data gathered in Chapter 1 to frame my findings.

I have adjusted the order and the focus of each step according to the nature of my data and research question.

2.8 Autoethnographic writing

It is a process of refiguring the past and in turn reconfiguring the self in a way that moves beyond what had existed previously. The backward movement of narrative therefore turns out to be dialectically intertwined with the forward movement of development [25]

The results section starts with an objective description of Lila, followed by an autoethnographic synthesis of data about each session. Each session has a title that describes my general feeling towards it, a word cloud that represents the most frequent words in the diary of that session, and several perspectives on what had happened during the session. I have specified the nature of each perspective with a color and a number:

- 0: Reflexive writing, my internal processes right before the start of the session;

- 1: Objective writing, my immediate and more objective observation of the session;

- 2: Second person perspective, my assumption of how Lila perceived the session;

- 3: Subjective writing, my subjective perception of the session, after-thoughts about the session, counter-transferences, and the effect of the session on the broader map of my life and mind.

These several perspectives are glued together with my current narrating voice, extracting experiences from them. To avoid redundancy, I have directly quoted the perspectives only when they shed new light on the reality of the session.

At the end of the results section, the word cloud of the whole diary is provided. I have used https://www.freewordcloudgenerator.com/ to generate the images.

In the discussion section, I have used the strategies described in the previous chapter to put the introduction and the results section together and make meaning from my experience.

3 Results

3.1 Introducing Lila

I started this journey with an adolescent that I was not naturally drawn to during my internship: Lila (pseudonym). A 15-year-old girl with severe cognitive and physical disabilities. In this section, I provide an objective summary of her condition as documented by the center where she lives in.

Lila is 15 years old. She suffered from placental insufficiency during pregnancy. The birth took place spontaneously in the 40th week of pregnancy. Lila was too small and light for her gestational age. Since she was not breathing spontaneously, she was intubated. She spent a large part of the first two years of her life in hospitals because of pulmonary infections and severe epilepsy.

Lila is completely dependent on the care and attention of others. She has spastic tetra-paresis, cannot speak, and is fed by a feeding tube. The general development is severely delayed.

Last year she had hip surgery and even though the operation was successful, she still suffers from post-operative complications.

An SEO test (Scale of Emotional Development [26]) was carried out for Lila, in which it was possible to find out or narrow down the emotional needs phase she is currently in. This has nothing to do with actual age. Accordingly, Lila is currently in phase 1, with a slight tendency towards phase 2. (Phase 1: 0–6 months = first adaptation/Phase 2: 6–18 months = first socialization)

3.2 Loving Lila

In the following twelve chapters, I give an overview of what Lila and I experienced during the twelve sessions of music therapy. Each chapter begins with a cloud of the most frequent words in my diary of that session, followed by a narration of the three different perspectives that I took after each session. I have specified the nature of each perspective with a color and a number:

- 0: My internal processes right before the start of the session (written in italics),

- 1: My objective observation of the session and the immediate perception of it (1st Person Perspective, written in present tense),

- 2: My assumption of how Lila perceived the session (2nd Person Perspective, written in capital letters),

- 3: My subjective experience, my afterthoughts about the session, counter-transferences, and the effect of the session on the broader map of my life and mind (3rd Person Perspective, written in past tense).

The chapters end with the codes that I extracted from the diary of that session. These codes along with the word cloud can be used to get a fast impression of the most prominent themes of each session.

3.3 Therapy sessions with Lila

3.3.1 Defeat at first sight

I remember when I walked into the center to start my first session with Lila, I was already regretting taking such a path that is full of unknowns. I did not know if I could build a therapeutic relationship with her; if I could find good enough results for my thesis; and if I would begin to love her, let alone investigate its effect on our relationship. I was missing the structures of a quantitative and objective methodology so much already.

Reading my diaries of that first session, I now realize how I had become small with all the doubt that was pressing down on me. Not finding the confidence to be present with her, I was projecting my own unresolved issues onto Lila. And I was struggling to differentiate the love that I had dealt with in my everyday life from the love that I was trying to cultivate in a therapeutic setting. I was confused and did not really know what I was doing.

Even though I had done those interventions for more than a hundred hours already, it was disorienting for me to think about loving Lila. It was disorienting for me to suddenly feel fearful when I caught a child’s eye contact with me, to feel jealous of the nurses who knew how to handle her better than me, and to doubt whether she was available for that connection at all. It is only with a retrospective lens that I can see how my own unresolved issues were hindering a genuine connection.

Even more than my 1st PP diary, I was shocked by reading my 2nd PP diary which looked more like a hate letter to myself rather than the perspective of a recipient of music therapy.

My already defeated attitude intensified after Lila started to cry during our session. A behavior that kept confusing me for a long time.

Reading my notes on the first session and the amount of confusion and doubt that I was feeling, I am happy that I was re-reading Free Play, an inspiring book, at that moment. A book that brought an empathic last paragraph to my diary of the day, encouraging me to take that leap into faith and have patience with myself and my learning journey:

#SELF_DOUBT #DIFFICULT_EMOTIONS #FEAR #DISAPPOINTMENT #UNRECIPROCATED_LOVE #PATIENCE

The word cloud for the 1st session is presented in Figure 1 [Fig. 1].

Figure 1: Word cloud first session

3.3.2 Bleeding of the souls and a half-smile

Being flooded with difficult emotions and associations that could impact my work with Lila, I decided to prepare myself more carefully for the next session. I knew I had unresolved issues to work on – issues that get triggered by the topic of love. I was projecting feelings onto her that were not in her best interest, and I was feeling defeated even before I took the journey. So, I started writing and wondering why it triggers me so much to work with Lila.

The eureka effect (also known as the Aha! moment or eureka moment) refers to the common human experience of suddenly understanding a previously incomprehensible problem or concept [28].

I had an eureka moment there on the train. I could see then, why I had not chosen to work with Lila in my months of internship and why my first session with her made me feel defeated. I was unconsciously excluding teenage girls from my clientele, as the teenage girl inside me needed some healing for herself.

I took some time to regulate the intense emotions that arose with this realization and sharpened my intentionality to be present with Lila, as she was.

I later realized that she was smiling, and half of her smile was paralyzed. That was a confrontational session for me, intensified by the interesting coincidence of my internal processes and her external bleeding.

#COUNTER-TRANSFERENCE #UNRESOLVED_ISSUES #OBSTACLES #COINCIDENCE #FINDING_CAPACITY #SURPRISES #PAIN #ENVELOPING #SELF_LOVE

The word cloud for the 2nd session is presented in Figure 2 [Fig. 2].

Figure 2: Word cloud second session

3.3.3 Love, pain, and blurred boundaries

My previous session with Lila was a pleasant and heavy surprise. I slept on the train that time maybe to literally sleep on the realization that I was projecting my teenage-self feelings onto her. My initial fear of not being able to love Lila had now expanded: “Will I be able to love myself?”

Not the parts of me that are cute and make baby-giggles, not the parts that look out the window and get fascinated by seeing the outside world, not the parts of me that move with the music and sing out of joy with it; but the parts that are sad, motionless, heavy, and not ready to stop crying with the sincere attempts of each person that walks into the door.

I started improvising to the rhythm of her breathing. She pleasantly surprised me by starting to sing early.

Suddenly she started spasming and crying. I tried to provide soothing sounds for her to relax, but the crying only got more intense. I stopped making music and held her hand. It did not seem to help. My supervisor suggested that we stop the session and take her back to her bed.

The session left me feeling angry. Angry about the pain that she had to experience and disappointed about my limitations in altering her state. My long conversation with my supervisor, Lila’s nurse, and the leader of the center helped me center myself in reality: there is only so much we can do.

#BOUNDARIES #EMPATHY #SUSPENDING_JUDGMENT #QUESTIONS #DISAPPOINTMENT #PAIN #OBSTACLES #LOVE

The word cloud for the 3rd session is presented in Figure 3 [Fig. 3].

Figure 3: Word cloud third session

3.3.4 Like a naked tree in the wind

Before our fourth session, I took a long time to allow all the difficult emotions that I had toward this journey to come to the surface. I was lacking comfort, certainty, and security; but I was proud for disarming myself of all the tools that could bring me those. I was coming to realize the importance of preparation more and more every day.

Her having all those spasms that I could feel in my hand and not crying came as a pleasant surprise to me. Even though I had prepared myself to hold her while she cries again, just as I had done for myself before the session. I was happy she sang with me so early in the session. She was in harmony with me, she was on beat. And she sounded sweet and kind.

I did not feel desperate. I had found a healthier stance towards her – someone I desperately wanted to connect to, but needed to be patient with. I suspended my need. I held my agenda back. I was present with her, and we had a nice session of togetherness in music.

#SURRENDER #PATIENCE #SPASMS #TOGETHERNESS #SUSPENDING_JUDGMENT #SYNCHRONY

The word cloud for the 4th session is presented in Figure 4 [Fig. 4].

Figure 4: Word cloud fourth session

3.3.5 Zooming out

I was becoming aware of how my life outside the music therapy room can affect the session. How my past, present, and ideas of future form how I show up, and how much capacity I have. I decided to actively pull out more information on this. Taking some moments before each session to zoom out and see myself in the bigger picture.

The potential of this practice kept surprising me throughout the journey. I decided to keep this habit of working with other children besides working with Lila as a gentle reminder to zoom out.

#TOGETHERNESS #PARTICIPATION #SYNCHRONY

The word cloud for the 5th session is presented in Figure 5 [Fig. 5].

Figure 5: Word cloud fifth session

3.3.6 Seasonal hugs

I noticed being a good enough music therapist and being a loving music therapist contrasted in my mind. Being a loving music therapist in my mind was more than being just enough. It would extend out of the room and the session and would penetrate deeper than the contact surface. It would set the bar higher and would make me question whether one can maintain the ability to be a loving music therapist despite the natural seasons of life.

With that question in mind, I started improvising on the piano, accompanying her exhales. I was beginning to admire the expressivity of the lullaby-like melody unfolding in F minor when I noticed that Lila was starting to cry. I abandoned my attachment to the unborn melodies and my heaviness went away as soon as I felt responsible to make her feel safe.

I stayed with her with no agenda as a music therapist, but rather as a protective figure. As a temporary parental figure. She stopped crying and looked around with wonder in her eyes. I started breathing together with her and singing out my exhales. She seemed to like it. I felt particularly good when she smiled at me singing “Hoohoo”.

At some point during this improvisation, I felt bad that this relationship had an expiry date. I felt bad that I was trying so hard to connect with her, knowing that I was not going to be there for her after my thesis. I felt guilty, like a mom abandoning her child. I felt ashamed of her.

I don't know how I can have such strong countertransference of a mother and child relationship, never having my baby. Where do my ideas of caring for her come from? The way I was cared for? Or a sort of Jungian collective unconscious?

#COUNTER-TRANSFERENCE #PATIENCE #FINDING_CAPACITY #EMPATHY #DETACHMENT #BOUNDARIES #MIRRORING

The word cloud for the 6th session is presented in Figure 6 [Fig. 6].

Figure 6: Word cloud sixth session

3.3.7 Self-disclosure

I acknowledged the triggering nature of this job before starting the session. Seeing children that are deprived of living in a family because of their condition; trying to connect with them but facing myriads of obstacles that stand in how we know communication as able-bodied people; and understanding that separation is inevitable.

I took some time to have empathy with myself for being so emotional those days.

When I saw Lila, I intuitively started doing vocal improvisation in Persian on the rhythm of her breathing. I was surprised by my decision, but decided to go with it and see how it affects us – me, Lila, and the music.

The experience of that session is still processing in my mind. I am happy that I gave in to my intuition and tried bringing something more of my background to the session. No matter if Lila was able to comprehend that I was speaking a different language or not, the effect of that allowance on my presence and our evolving music-sphere was substantial.

#TRIGGERS #INTUITION #SURPRISES #VULNERABILITY

The word cloud for the 7th session is presented in Figure 7 [Fig. 7].

Figure 7: Word cloud seventh session

3.3.8 Looking at the mirror to see you

Before the session, I had a hard time motivating myself to get on the train with the physical cramps that I was experiencing. It was like I needed some sort of external acknowledgment of my effort to justify it.

At the center, I noticed how beautifully Lila’s hair was done. I was thinking, of course, she doesn't see how beautiful her hair looks, but the nurses still do that. I was happy I showed up. Participating in the world of Lila, along with the nurses and anyone else who does their best.

I noticed that I am more secure with her, as her spasms come and go. I do not question myself. I know that I am not her spasms, and I cannot stop them. The best I can do is to be with her while she is experiencing them – calm and confident. The spasms seemed to go on for a shorter while compared to our first sessions. She had a couple of short spasms, and the relief always came afterward. Her smiles were also longer this session. It was the first time she looked at me with a smile. As I was smiling back at her and singing with a teary voice out of excitement.

I thought about how Lila is also getting to know me as I am getting to know her. She might recognize my face now, know my voice, and have an idea of what usually happens when this face and voice are there with her.

I noticed how we are both having spasms, how we are both smiling with teary eyes. We share more than we know. This gave me a more equal stance toward her. More of a being together in this experience rather than me doing things to her world and hunting for rewarding smiles.

#HOPE #DOUBTS #SPASMS #SURPRISES #MIRRORING

The word cloud for the 8th session is presented in Figure 8 [Fig. 8].

Figure 8: Word cloud eighth session

3.3.9 Feeling lost at times

Unlike every other session, I don’t have much written data on what I was going through before this session. This is all I had written down before that session:

So, I’m pulling data from my memory. I remember I had encountered some articles about the phenomenological interpretation of music [21] the night before. So I spent my usual reflection time reading those articles, hoping to find more structure and orientation for my research. I can remember now, how I was seeking refuge in published articles to get away from the discomfort of having to hold so much uncertainty in the process of finding my own voice.

Eyes, mouth, and breath. These were my main clues to her world. I had been hyper-vigilant about those non-verbal cues even before my profession as a music therapist started. I told my psychotherapist that week, what a funny Viktor Frankl coincidence it is to turn a coping mechanism into a profession.

The downside of pulling out from my childhood’s hyper-vigilant resources was the negative associations and projections that would come with it. I would feel like a hanging fruit – an abandoned child – when her nonverbal cues were cold and distant. Then I had to take a moment to be present and orient myself out of that counter-transference. I wanted to be patient with myself and with Lila.

As the session ended, I had the urge to dilute my experience with something. With oat milk or coffee, with some stretches, or looking out the window. I had a hard time. My expectations were giving me a hard time. And also, a tinge of regret about not choosing a more interactive kid. I noticed how easily I got disappointed at the moment.

#VULNERABILITY #DISAPPOINTMENT #EXPECTATIONS #COUNTER-TRANSFERENCE #OBSTACLES

The word cloud for the 9th session is presented in Figure 9 [Fig. 9].

Figure 9: Word cloud ninth session

3.3.10 A call into existence

I had a stormy preparation before our 10th session.

I confronted the image of a hanging fruit that arose in our previous session and kept pulling its thread until I was called into existence – my first reception of love; and until I responded to that call with the most joyful of sounds – my first act of love.

I let the words flow mindlessly and emotions come to the surface and take over me for a while.

The relief came naturally, just like a rainbow after the rain. I had a sense of closure with my recollections of neglect, which was not why I had initially started this study; but for which I was grateful.

I prepared my mind for the session by reading the opening poem of “Inside Music Therapy” by Julie Hibben (1999) as I had done several times before:

I had embodied what I had been studying for a year now: unconditional positive regard. Is it not one of the thousand names of love?

I could see the effect of my altered perspective around love in the therapeutic work with other children as well. I could come to the center and only work with Lila then, but I was happily working with other children as well. After almost a year of working together, I heard one of my favorite children saying her first word: “Mama.”

I took it in.

I embraced the Mama inside me, and the infinite capacity to love.

#COUNTER-TRANSFERENCE #UNRESOLVED_ISSUES #PERSPECTIVE

The word cloud for the 10th session is presented in Figure 10 [Fig. 10].

Figure 10: Word cloud tenth session

3.3.11 Some Sort of Closure

Starting saying my goodbyes one day before the last day had been my ritual for at least ten years – since I left my first home to study in another city and live on my own. This had been my way of coping with the intensity of emotions that I felt about separation: diluting them in time, taking some pressure off the moment of departure.

After the session, I did not feel like writing much, but I pushed myself to stick to the protocol:

I felt like the three voices that would initially help me perceive our sessions better were merging into one.

#COUNTER-TRANSFERENCE #HARMONY #SYNCHRONY #ATTITUDE

The word cloud for the 11th session is presented in Figure 11 [Fig. 11].

Figure 11: Word cloud eleventh session

3.3.12 Snowflakes in the sun

Before the session, I felt sad and angry for having to end this journey. I found myself holding longevity as a core value in my relationships – therapeutic or not.

“What are you in my life if you don’t stay forever, and what am I in your life if I have to leave?”

I realized how this value can limit my ability to be present wholeheartedly.

I noticed how the fear of the moment of separation crawls under my skin when I am about to touch and trembles in my voice when I am about to call.

I decided to write a letter to Lila before working with her for the last time. I knew by then that even though she did not understand my words, the words I used affected our relationship by affecting me and the music we make.

No matter how I primed myself for our last session, a surprising wave of disappointment took over me when the session came to an end, without Lila smiling at me or vocalizing even once. I kept calm and said goodbye to her to attend to those intense feelings.

I needed a spark, a spice, a smile. I guess that’s the dark side of loving in this work. I am confronted with the hope that I didn’t know I was having – by losing it. I want to gather myself and go back home.

As a result of the anger and disappointment that took over me, I did not stay to reflect on the session by taking different perspectives. I let myself be the bored and disappointed child that just wants to go back home. I gave myself the right to deviate from the protocols for the day.

It was days after the session that I could get my head around our last session and accept.

Accept whatever showed up,

Accept the silence,

Accept the eyes that appeared blank to me,

Accept the limitations of my sensory receptors to perceive the world and the connections that I make in it,

Accept that sometimes, it’s only so much change that I can induce – if any at all,

And that one cannot profess love without first approaching acceptance and releasing expectations.

I remind myself of this poem from Hafiz, the Persian poet [30].

I have enjoyed my one or two cups of getting to love Lila. It’s time to let her go.

#VULNERABILITY #DETACHMENT

The word cloud for the 12th session is presented in Figure 12 [Fig. 12].

Figure 12: Word cloud last session

4 Discussion

This study began with a series of questions that I will repeat to form the discussion (the word cloud for all sessions is presented in Figure 13 [Fig. 13]).

Figure 13: Word cloud including all sessions

4.1 What is love in a therapeutic relationship?

As mentioned in the introduction section, love is not the same thing for everybody, and this applies to the practitioners of healthcare as well. Professional distancing was a safe and sustainable stance for me in the years that I worked as a pharmacist, both as a researcher and as a practitioner. However, that stance felt inauthentic and fragile after my prolonged and intimate encounters with my clients in the practice of music therapy. Studying the literature on love, going through twelve intense sessions with Lila, and reflecting on the absence or presence of love between us, made me believe that love in a therapeutic relationship is what we allow it to be. It can be nothing. It can also be the background of everything. To find our place in this spectrum is to define our attitude toward love. Therefore, I believe that love in a therapeutic relationship is at its best when it starts with a mindful attitude, rather than an emotion; when it’s practiced actively, and not passively; and when it’s paired with intensive self-reflection.

I started this study holding love as an ambiguous emotion with unknown effects on me and my clients. Going through this study and facing my strongest fears around love made me develop a new perspective toward it. One rooted not in accidental emotions, but in the robust belief that every human is worthy of love, no matter if others find the capacity inside them to actualize that love or not.

As mentioned in the introduction section, feeling loved has a crucial role in our ability as humans to develop a secure base, experience ourselves, and form healthy relationships [10], [14]. One can imagine that a great percentage of referrals to psychotherapy could result from being deprived of love and its associating behaviors at some point in life. Therefore, having a loving attitude in a therapeutic relationship can be a valid way of shedding light on what had been lacking and providing a corrective experience.

4.2 Does love necessarily appear in the process?

I initiated this study to investigate when love is but ended up struggling with when love wasn’t and isn’t. A struggle that even though is one of the most painful human experiences, can reveal the importance of love in human life like no other experiment.

Answering the question “Does love necessarily appear?” remains impossible due to the nature of this case study, as one cannot conclude that all the ravens are black after seeing a thousand black ravens [31]; however, I hypothesize that love is possible in any therapeutic relationship if the therapists hold this belief that all humans are worthy of love and decide to incorporate their natural emotions into their professional practice as long as this does not cause harm to themselves or the clients.

In this study of three cases, Lila, me, and our relationship, I was pleasantly surprised to find most of the obstacles of love within myself and my unresolved issues, rather than in Lila’s cognitive and physical disabilities. This gave me the perspective that studying love is precious, especially in its absence. Taking Solomon’s theory of four dimensions of love into consideration, a therapeutic relationship can have all four of these dimensions: intensity, projection, idealness, and time [4]. Therefore, the question of whether or not love appears in that shared reality is valid and relevant regardless of the answer.

Even though this study cannot answer this question, I believe that there is value in continuing to ask it. Reflecting on the absence of love, as done in the earlier sessions, gave me valuable insights into my relationship with love and my counter-transferences. On the other hand, reflecting on the presence of love, as done in my latest sessions with Lila, reinforced my ability to provide a safe and accepting space for her.

4.3 How does the presence of love affect the therapeutic process and outcomes?

As mentioned in the introduction, love has been known to activate numerous systems in humans, some of which could be in line with a therapeutic relationship and some not. The great potential of incorporating love into a therapeutic relationship has been addressed by some psychologists and psychotherapists. As famously expressed by Freud in his letter to Carl Gustav Jung, defining psychoanalysis as “in essence, a cure through love” [32].

Erich Fromm’s definition of love in Man for Hims is also in line with the general concept of a therapeutic relationship:

Love is the productive form of relatedness to others and to oneself. It implies responsibility, care, respect, and knowledge, and the wish for the other person to grow and develop. It is the expression of intimacy between two human beings under the condition of the preservation of each other’s integrity [33].

However, one can imagine that the practice of professional distancing and avoiding the incorporation of emotions in therapeutic work has been popularized to serve some purposes. To have a loving attitude in the therapeutic relationship is a double-edged sword. Considering the six constructed types of love introduced by Lee (1977), self-revelation, mutual need-fulfillment, and interdependency of a storgic love could rob a therapeutic relationship of its main goals, while its rapport could support it. The unconditional nature of an agapic love can support a therapeutic relationship, while its self-sabotaging potential might cause burnout. Just like the obsessive and possessive thoughts associated with manic love, Ludus, and Eros that conflict with the fundamental maxim of a therapeutic relationship: cause no harm [34]. In the end, introducing love as an attitude to a therapeutic relationship (rather than an emotion) makes it look more like a pragmatic love. Therefore, it remains the therapist’s responsibility to incorporate only the variations and qualities of love that can serve the client and their therapeutic relationship [35].

Apart from the variations of love, there are certain behaviors associated with love that are also practiced in a therapeutic relationship. Empathy, warmth, acceptance, respect, and sensitivity in responding to the client are among the common therapeutic factors in psychotherapy [36] that are similarly expected in a loving relationship.

According to [12], [11], eye contact, holding, touching, caressing, smiling, crying, clinging, a desire to be comforted by the relationship partner when upset, the experience of anger, anxiety, and sorrow following separation or loss, and the experience of happiness and joy upon reunion are all characteristics of love in both infancy and adulthood. Furthermore, the development of a stable relationship with either a main caregiver or a romantic partner depends on the sensitivity and responsiveness of the caregiver or partner to the closeness bids of the increasingly attached person. The attached person becomes happier, more outgoing, more confident, and more compassionate because of this responsiveness.

Considering all these facts, a therapist can find great potential and serious threats in incorporating love into the therapeutic relationship. One of the threats that arose in my case study was the intensification of my unresolved issues around love and lovability, which caused significant emotional distress for me. However, dedicating enough time to do intense self-reflection and emotional regulation between my sessions turned that threat into a great chance for me to detangle past issues. Furthermore, it proved the importance of seeking supervision and continuing my personal psychotherapy for my future development.

Looking back at the effect of taking a loving attitude in my therapeutic work with Lila, I can see that love allowed me to be more perseverant and present in my work. It helped me redirect my focus from the results to “togetherness”, to fall back to basics: being human and being together. It helped to identify the other within myself and practice empathy more effectively. To gain ownership of the inevitable entanglement of my emotions within my work, to be more grounded, authentic, and whole in my sessions. To see the other in a new light, and recognize their potentials and abilities, in contrast to focusing on what is suboptimal and being change-oriented. Love also made me more vulnerable and sensitive to disappointments.

Given that the literature on love is mostly focused on the romantic kind of love and the scarcity of literature on the presence of love in a therapeutic relationship, there is no consensus on why and how to love in a therapeutic relationship. This requires the multiplication of this study in different settings, populations, and backgrounds to better identify these risks and benefits and tailor this fundamental human phenomenon to serve us best in our therapeutic work.

4.4 Closing remarks on the methodology of this study

Taking an autoethnographic case study as my methodology made this journey full of fear, hope, and surprising transformations in my identity as a music therapist in progress. Choosing this methodology had a sharp contrast with the methodology of my previous degree, where I did a randomized controlled trial to measure the effectiveness of physical exercise in preventing chemotherapy-induced cognitive dysfunction. My methodology back then was robust, predictable, and did not include anything beyond the contact surface of me with the rats that I experimented with. During my case study with Lila, I was disturbingly reminded several times of how I had to kill those rats after the experiment. I believe those memories played a major role in my research stance in the current study. This does not mean that I discourage the use of animals in scientific experiments when necessary. However, that experience made me become critical about doing prescribed research and encourage myself and every student to reflect on why they choose a specific methodology, and how it interacts with their personality, their research question, and the population of their research study.

5 Conclusions

In my love experiment with Lila, I found love to be a natural consequence of getting to know her and getting to know myself through her. After confronting the strong unpleasant counter-transferences that she awoke in me, I came to believe that the few things that can prevent therapists from loving their clients are either actively avoiding it or not looking closely enough within themselves to find astonishing similarities. As time is a key factor in processing unresolved issues and shedding light on the realm of shadows, I found this kind of love to fall under the four-dimensional love described in the introduction [4] The committed kind of love that features intensity, projection, idealness, and, more importantly, time.

Considering the developmental importance of love and the transformative effect of this case study on me, I suggest the incorporation of love as a clinical decision in therapeutic work. I find this approach to be practically similar to Carl Rogers’s practice of unconditional positive regard [19]. I believe that this approach empowers me as a music therapist to actively seek love as a natural consequence of genuine human connection, brings a more equal stance to the relationship, and fosters hope and perseverance in the therapeutic process.

I hope that over time, as participants in healthcare, we can define therapeutic love with respectful and professional boundaries and advocate for its inclusion in the categorizations of the term. This sort of categorization can better encourage the students and practitioners of healthcare to examine their relationship with themselves and therefore, with their clients.

Growing up in a society that shies away from love, condemns it, and even punishes it, I found it extremely challenging to think about love, talk about it, and even worse, write about it. However, I believe that this act of “actively pursuing the uncomfortable” contributes to my ongoing journey as a music therapist and as a responsible member of the societies in which I grew up or currently reside.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

This study is limited by some factors according to its design and nature.

Methodology: Following the nature of an autoethnographic case study, the results of this study are based on my experience of the appearance of love in a therapeutic relationship. I believe that taking the opinion of a large number of experts and more experienced practitioners in a qualitative study could help further define the phenomenon of love in a therapeutic relationship.

Population: I conducted this research with one case. Even though this approach helped me go in depth about the experience, its results might not be replicable in other populations. Considering the great potential and sensitivity of the topic, I suggest doing the same study with other populations in the future.

Time: Since this study was conducted in a thesis framework, the outcomes could not be studied for a longer time. However, I believe a long-term study can be beneficial in better understanding the risk and benefits of actively pursuing love in a therapeutic relationship.

Ethical Considerations

A central ethical concern in psychotherapy arises when the term love is used to describe the therapeutic relationship. Within professional ethics codes, love relationships between therapist and client are sanctioned because they generally refer to sexual or romantic involvement. Such relationships violate professional boundaries and can cause significant harm, which is why they are rightfully prohibited [34].

The present study does not address this form of love. As mentioned in the introduction, love can take different shapes and forms, and my use of the term “love in the therapeutic relationship” differs fundamentally from romantic or sexual love. Here, love refers to relational qualities such as care, attunement, acceptance, and the capacity to hold the client in a secure relational space. These qualities are consistent with professional ethics and resonate with established therapeutic values such as empathy, unconditional positive regard, and authenticity. In this sense, love is understood as an ethical, non-sexual phenomenon that can enhance well-being and support personal growth in therapy.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [37], and informed consent was obtained from Lila’s guardian. Additional safeguards included ongoing supervision and reflective practice to ensure ethical integrity throughout the research process. All identifying details have been altered or anonymized to protect Lila’s privacy and confidentiality.

Notes

Competing interests

The authos declares that she has no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors for their invaluable support throughout this study. Special thanks go to Mr. Hansjörg Meyer-Sonntag, whose encouragement to pursue a topic close to my heart, and whose provision of space and guidance, were essential to the development of this work. I am also deeply grateful to Dr. Fabian Chyle-Sylvestri for his guidance in bringing clarity and structure to a subject that was inherently broad and open-ended, helping shape the study into a coherent and focused piece of research.

I further extend my appreciation to Lila’s guardian and the dedicated staff of the center who made this research possible.

Funding

I received no financial support for this research.

References