[Conditions and effects of online creative arts therapies – a systematic review and change factor categorization]

Renate Oepen 1Corinne Roy 1

Harald Gruber 1,2

Eva Paul 1

1 Department of Art Therapies and Therapeutic Science, Alanus University of Arts and Social Sciences, Alfter, Germany

2 Research Institute for Creative Arts Therapies (RIArT), Alanus University of Arts and Social Sciences, Alfter, Germany

Abstract

Background: Technological progress is driving the development of online therapy, including in the field of creative arts therapies (CATs). Previous research results often reflect the therapists' point of view. This review therefore investigated which contextual conditions apply to online arts therapies programs for different target groups, what effects can be observed in various test groups, and which insights can be gained for future research and practice.

Methods: We conducted a systematic literature review to analyze research results published between 2021 and 2024. We searched the databases APA PsycINFO, Academic Search Ultimate, APA PsycArticles, ERIC, MEDLINE, OpenDissertations, PSYNDEX Literature with PSYNDEX Tests, and SocINDEX with Full Text.

Results: Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria, nine of them used qualitative methods. Among other things, we observed the following effects of online arts therapies: (a) for people with disabilities: an increase in self-confidence and the formation of social contacts; (b) for older adults: a promotion of an integrative view of life; (c) for participants in health promotion programs: stress reduction and increased well-being. Online creative arts therapies approaches appear to be particularly helpful for people with poor access to face-to-face therapies due to geographical-, or time constraints or illness-related barriers.

Discussion and Conclusion: Online creative arts therapies formats offer both significant benefits and challenges. These must be carefully considered and systematically investigated to achieve the best possible therapy outcomes for different patient and client groups within creative arts therapies.

Keywords

creative arts therapies, digital technologies, online therapy, therapeutic factors, health promotion, systematic review

Background

Digital technologies are increasingly being used in psychotherapy worldwide, enabling remote connections between clients and therapists. Initially, little was known about their application in the field of creative arts therapies [Choe, 2014; Levy et al., 2018 cited in Zubala et al., [1]]. Although computer-assisted technologies were already being developed before the coronavirus pandemic, they were rarely used [2]. Among these were art therapy apps, which offer tools that enable virtual access to a therapist or use physiological sensors to track moods throughout the day [3]. The demand for online therapies has risen sharply, particularly due to the client isolation during the coronavirus pandemic. This is reflected in the significant increase in the number of articles on online-based art therapy published since the beginning of the pandemic [2]. Given continuing technological progress, it can also be assumed that the importance and use of online-based therapy forms will increase, as access to mental health care is facilitated in this way and treatment costs can be reduced [3], [4].

Many different terms occur in the literature and research for digital forms of creative arts therapies (CAT). Malchiodi [5] refers to all forms of technology-based media that support clients in creating art as part of the therapy process. The specific form of online-based arts therapies (=OCATs) is a form of distance therapy, which is carried out via video, chat, telephone, virtual platforms or other forms of electronic communication [Malchiodi, 2018 cited in [2]] (Note: In Germany, the term “therapy” is not used in a preventive context. Among others, the term “artistic counseling” is used. In practice, therapy-like interventions often take place, so the internationally varying terms "eHealth", “tele-CAT”, “tele-health”, “remote therapy”, “online therapy” and “counseling”, and the like, are used synonymously in this article).

For distance therapies in particular, in contrast to face-to-face therapies, it seems advisable to identify their specific requirements and modes of action for different target groups, and then to use these findings to further develop intervention concepts in both practice and research. This aspect appears especially relevant in light of the fact that current research findings often rely on surveys of therapists. While the views of clients – their experiences, attitudes, and outcomes – remain insufficiently known [Kapitan, 2009; Edmunds, 2012; Carlton, 2014, cited in [1]].

Advantages of online-based therapies include high acceptance among both patients and therapists, worldwide availability, and increased client autonomy. A notable disadvantage is the lack of tactile qualities, which represents a significant loss, as the haptic aspects of art therapy cannot be conveyed online. It was also more difficult to manage crisis situations remotely, and access to online art therapy required technical expertise, which limited access for some clients. Ethical concerns were raised by therapists regarding trust in the therapeutic relationship and the loss of control when conducting online session, especially in crisis situations. In addition, sone clients may be resistant to online therapy, although such resistance can be reduced through user-friendly technologies. Finally, the lack of physical interaction may cause clients to disconnect from social interactions and feel more isolated [1], [2], [4], [6], [7].

In creative arts therapies research, the question of active factors in this form of therapy – still not fully clarified – arises repeatedly. In particular, this question must be raised with regard to the effects of online-based therapies. Based on findings from psychotherapy research, a distinction can be made between common and specific change factors [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. The quality of the therapeutic relationship generally accounts for more than 50% of the variance on therapy outcomes [Grawe et al., 1994, cited in [10]. According to Grawe, the common factors include the therapeutic relationship, resource orientation, problem actualization, motivational clarification, and problem solving. When analyzing the studies in this review, the classification by Grenvavage and Norcross [9] for describing common factors proved particularly helpful in interpreting the results. The authors cite the following common factors: patient and therapist characteristics, change processes, treatment structure, and the therapy relationship (cf. Results and Discussion).

The specific change factors of artistic activities include the symbolic language of images, which creates access to resources and allows for a fear-free confrontation with inner conflicts [10], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. Creative arts therapies can reach individuals nonverbally via the senses and promote successive integration, which can lead to emotion regulation, transformation, and therapeutic change [15], [18], [19], [20]. This article focuses on studies that use visual art techniques and art therapy interventions, often in combination with other forms of creative arts therapies and related activities (see inclusion criteria).

This raises the question of the conditions under which a similarly positive, health-promoting effect can be achieved online as in face-to-face therapy. For example, the “art therapy triad” (therapist (relationship) – client – artwork)) may be more difficult to establish in an online setting [Schaverien, 2000; Gussak and Rosal, 2016, cited in [1]]. There is little research available on the design and impact of OCATs for different target groups. Systematic research would help to better understand the use and challenges of OCATs in various fields of practice. This is particularly important because arts therapists work with a wide range of target groups- people of all ages, with different clinical conditions and symptoms – in clinical, rehabilitative, and preventative contexts. To the best of our knowledge, there has not yet been any research into common change factors in this context.

In order to identify key issues for practitioners and determine future areas of research, current research findings on the impact and design of OCATs should be summarized and synthesized. Specifically, the research questions guiding this review are as follows:

- What framework conditions and effects of OCATs are reported in current research for different target groups?

- What are the implications for future research and practice?

Methods

Database research

This review analyzes current studies in which artistic-therapeutic interventions were offered and conducted online. The study period focuses on the years 2021 to 2024 (January 1, 2021–May 27, 2024), a time when it was expected that more online therapies would be offered due to the coronavirus pandemic and the associated lockdowns. A higher demand on the part of clients was assumed, resulting from the isolating conditions of daily life during this period, and this special situation was also expected to lead to an increase in studies.

The study results from this period could answer the research questions regarding target group selection and suitability, particularly in relation to the specific modalities involved in the implementation of therapy and their modes of action. The insights gained could be considered future research on online therapies and in the planning of online programs.

In this systematic review [21], [22], the studies were identified and analyzed using the PICO framework. The PICO or PICOs framework contains a checklist of elements commonly used in systematic reviews to provide an explicit structure for addressing the issues under investigations, focusing on patient, interventions, control, outcomes, study design=PICOS) [22], [23]. This framework is very well suited for the investigation of therapeutic questions [24]. The search was broad in scope (see search criteria) to comprehensively determine the current state of research according to the research questions and to provide an overview of all areas of application and target groups.

The following databases were searched: APA PsycINFO, Academic Search Ultimate, APA PsycArticles, ERIC, MEDLINE, OpenDissertations, PSYNDEX Literature with PSYNDEX Tests, SocINDEX with Full Text. The following search terms were used: (art therapy or art psychotherapy or creative arts therapies or expressive arts therapy) AND online art therapy AND digital art therapy. The search terms covered a wide range of health-related arts activities (art, art therapy, arts therapies (including art, music, dance, theatre and poetry therapy)). This search was supplemented by publications identified through hand searches and expert knowledge.

The systematic literature review method used in this review was defined as follows [25]

The results of the review are presented in a narrative, storytelling format [27].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion

Studies that investigated art therapy interventions or artistic activities in an online format – either exclusively or in combination with other arts therapies or techniques – were included. A key selection criterion was that the studies employed validated empirical methods, such as quantitative and/or qualitative data collection instruments or arts-based research methods. As research on OCATs is still a relatively new field, studies of all evidence types (I–IV) were included in order to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research in this area.

Exclusion

We excluded studies that did not investigate creative arts therapies or artistic activities according to the inclusion criteria. We also excluded case reports and reports on creative projects, intervention tools, training programs, as well as studies on ART (=antiretroviral therapy), due to confusion with “art”. In addition, we excluded studies that investigated the use of digital media in face-to-face settings (see also [28]).

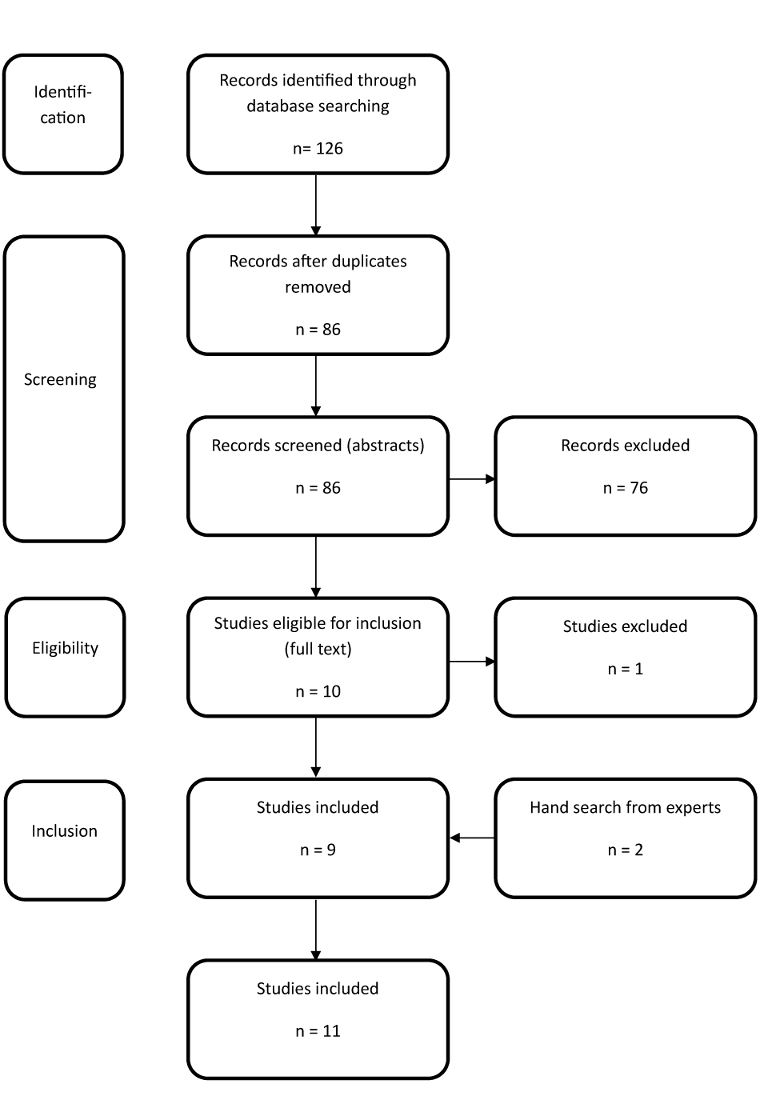

The following overview (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]) presents the individual steps of the search process according to the PRISMA guideline [22].

Figure 1: Information flow through the various phases of synthesis

Results

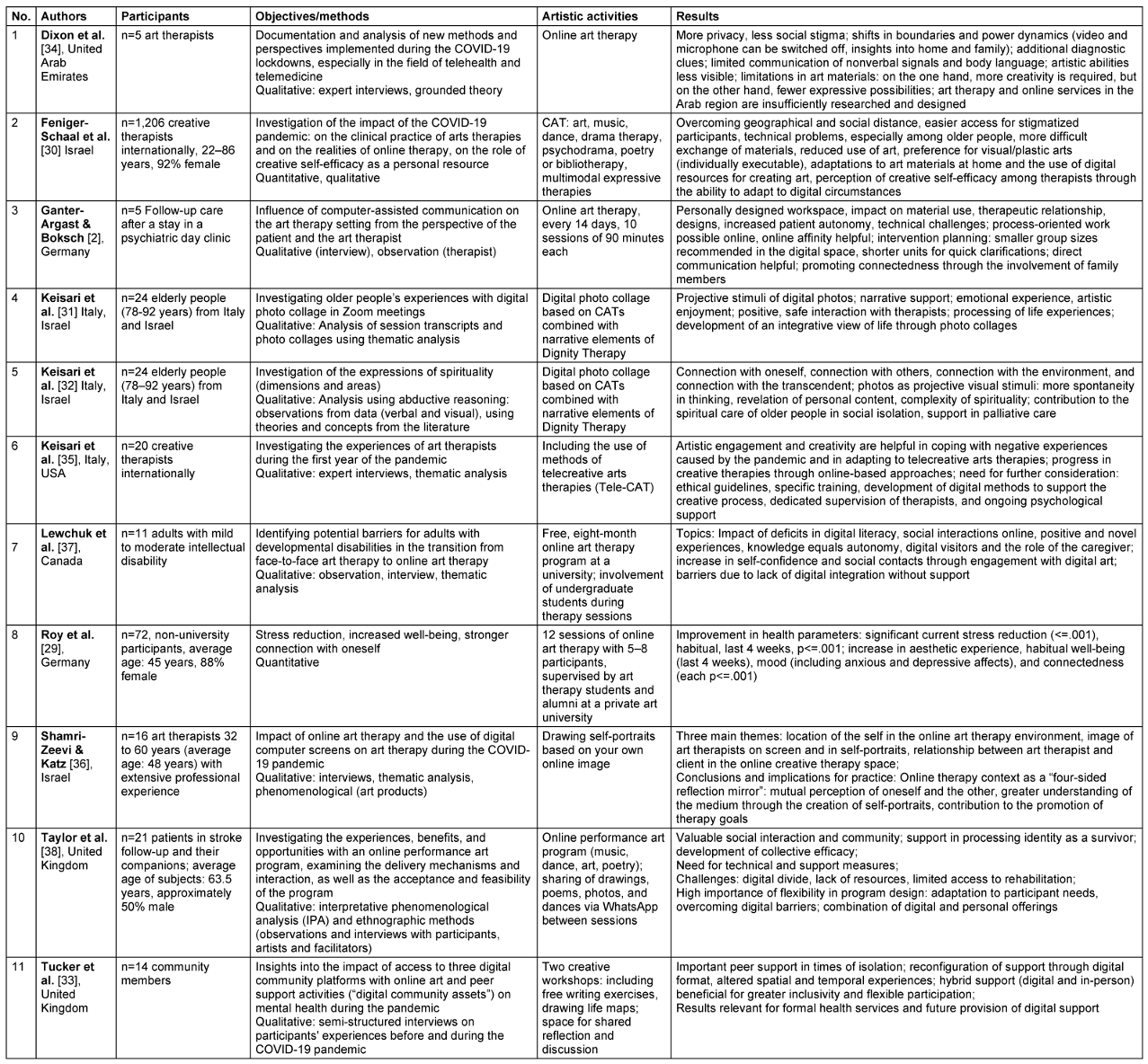

The initial search yielded 126 studies, with 86 studies remaining after duplicates were removed. Ultimately, we identified a total of 11 studies from the period 2021– 2024 that met the inclusion criteria (see Table 1 [Tab. 1]). We considered it necessary to first record the characteristics of the selected studies according to the PICOS criteria [24].

Table 1: Summary of the Research Results

In line with the research questions, the presentation of the results focuses on the experiences that different groups of subjects had with online art therapy programs – particularly regarding framework conditions and effects, the impact of OCATs or artistic programs, and their specific requirements. It should be noted that nine studies used qualitative research methods, while the studies by Roy et al [29] and Feniger-Schaal et al. [30] employed quantitative methods.

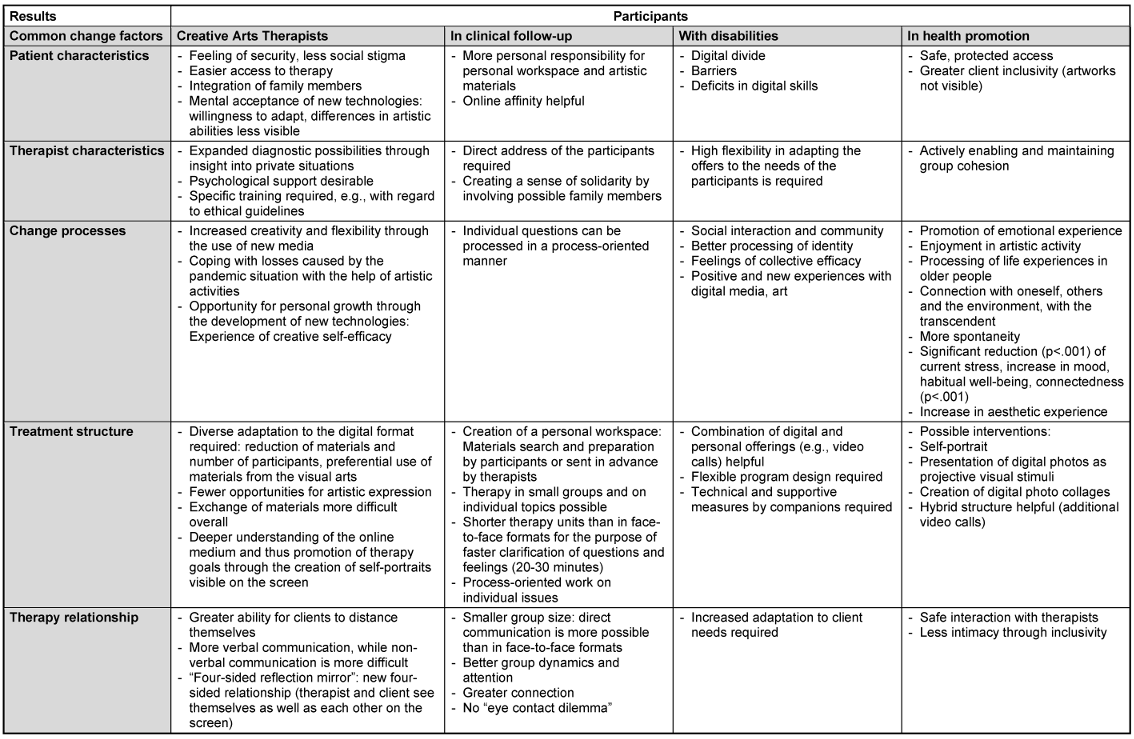

Among the included studies, the identified test subjects included arts therapists (expert interviews and surveys), patients in follow-up care after acute illness (psychiatry), and people with disabilities (such as brain injury following stroke or intellectual development disorders). In the field of health-promoting interventions, studies were conducted with older adults [31], [32] and with clients and participants who showed an interest in new intervention programs during the isolation phase of the pandemic [29], [33]. The experiences of the respective target groups are discussed in the following section. In summary, these experiences are then mapped onto the common change factors of psychotherapy according to Grencavage and Norcross [9] (see Table 2 [Tab. 2]). In addition, specific creative arts therapies factors are extracted from the common factors.

Table 2: Common factors of online creative arts therapies and counseling for different target groups

a) Online creative arts therapies from the therapist’s perspective

Four of the selective studies focused on the experiences of creative arts therapists with online therapy [30], [33], [34], [36]. One study showed both the therapist and the client perspective [2]. The therapists’ statements indicated that OCATs can support clients with a variety of conditions, including anxiety, depression, emotional difficulties, and behavioral problems. Online therapy offered increased privacy, which in turn reduced social stigmatization. As a result, participants felt safer and less judged [30], [34]. In addition, OCATs made it possible to overcome geographical and social barriers, thereby providing stigmatized individuals in particular with easier access to therapy [30]. Online therapy led to shifts in boundaries and power dynamics, as clients were able to switch off the video and microphone. On the other hand, therapists gained the opportunity to observe aspects of the client’s private environment, thereby obtaining extended diagnostic insights. Although the presence of family members sometimes compromised participants’ privacy, it also gave therapists additional diagnostic information [34]. Moreover, conversations with family members helped consolidate therapeutic issues, which were beneficial for clarifying problems.

Online therapy programs promoted client flexibility in the use of art materials and in the adoption of new technological processes. In some cases, participants had to independently organize and experiment with artistic materials [2].

We observed that creativity was encouraged through adaptations such as using art materials available at home and integrating digital resources [34]. Artistic engagement and creativity served as crucial parameters for therapists to process losses related to the pandemic and supported their adaptation to digital media [35]. However, therapists also encountered restrictions in using diverse techniques within the online setting. Visual and plastic arts were favored, as these could be practiced independently [30]. While limitations on art materials sometimes prompted greater creativity, they also offered participants fewer avenues for diverse artistic expression. We noted that differences between expert and novice skill levels – based on clients’ prior artistic experience – were less apparent in online therapies [34].

Regarding communication in online therapies, verbal exchange increased [30], whereas non-verbal signals and body language became more difficult to perceive [34]. Technical difficulties posed a consistent obstacle, as digital communication was susceptible to disruption, and sharing materials proved more challenging than in face-to-face settings [2], [30]. Older adults often struggled to adapt to new technologies, which contributed to a decline in client numbers. Many required assistance from family members to manage the technical demands. Mental acceptance of teletherapy emerged as a crucial step in the adjustment process, one that was not always easy for clients [30].

We observed that the pandemic spurred innovation in response to new therapeutic challenges, fostering both personal and professional growth among therapists [30], [35]. The experience of creative self-efficacy in engaging in therapy programs helped mitigate the negative impact of therapists' limited digital competencies [35].

A distinctive feature of the online therapy environment was the so-called “four-sided reflection mirror”: therapist and client could simultaneously see both themselves and each other on screen. By creating self-portraits with the online medium, art therapists reported gaining a deeper understanding of the medium itself [35], [36].

When designing online therapy programs, therapists expressed the need for additional supportive measures. For example, they emphasized that psychological support plays a key role in reducing therapist burden during challenging events such as a pandemic. Finally, the shift to OCATs requires ethical guidelines, targeted training, and the development of digital methods that support the creative process to ensure effective responsible and effective implementation [35].

Regarding the specific design of therapy programs, the study by Ganter-Argast and Bocksch [2] – which involved patients in clinical aftercare following psychiatric illness – offered additional insights. Patients reported that the so-called “eye-contact dilemma” was irrelevant in the online setting, and they found that the process-orientated work on individual topics could be implemented with ease. Group art therapy group sessions were also successfully adapted to include digital components, especially for tech-savvy patients. In this context, therapists found it helpful to reduce group size in the digital format, as this improved group dynamics and attention. Because of the physical distance between participants, individual support could only be provided through direct communication. Therapists recommended shorter sessions of 20 to 30 minutes to allow clients to address questions and feelings more quickly.

A study by Dixon et al. [34] focusing on art therapists in the Arab world revealed specific challenges related to online services. Therapists noted that both art therapy and the use of online serves in the region remain under-researched and insufficiently structured.

b) Online creative arts therapies from the participants’ perspective

(1) People with disabilities

The study by Lewchuk et al [37] aimed to identify potential barriers in the transition from face-to-face art therapy to online services for adults with mild to moderate intellectual developmental disabilities. In this study, it was essential to establish a baseline for this population's prior engagement with, and challenges in, digital spaces and technology. A thematic analysis of interviews and observations identified the following key topics: the impact of digital literacy deficits, online social interactions, positive and novel client experiences, knowledge as a pathway to autonomy, digital visitors, and the role of the carer.

We observed that participants appeared to gain confidence, increase their social contact with others, and engage more actively with digital art during their time on the program. These results underscore how the lack of digital inclusion can create unnecessary barriers for adults with developmental disabilities. Support from facilitators (undergraduate students) in accessing both online and digital art therapy was reported as helpful [37].

In the study by Taylor et al [38], which focused on individuals with people with acquired brain injury from stroke, OCATs were found to offer valuable opportunities for social interaction and community. It also supported identity processing as stroke survivors and promoted the development of collective efficacy. We found that technical and supportive interventions from facilitators were also necessary for this target group in order to maximize the benefits of both online and face-to-face sessions and to foster a sense of community. Challenges such as the digital divide, lack of resources, and limited access to rehabilitation services still need to be addressed. Flexible program design emerged as a key supportive measure, as it allowed therapy to be tailored more specifically to the needs of target group participants and helped to circumvent digital barriers. A combination of digital and in-person sessions (e.g., via video calls) was considered recovering from stroke.

(2) As an offer of health promotion

In a study with older people [31], [32], digital photos were used as projective visual stimuli to evoke participants' narratives and promote emotional experience. Very old participants reported joy in the artistic activity and described their interactions with the therapist as positive and safe. Creating photo collages supported the processing of life experiences and fostered the development of an integrative view of life [31]. In an additional study on expressions of spirituality with the same participants [32], researchers identified four main categories of expression: connectedness to self, connectedness to others, connectedness to the environment and connectedness to the transcendent. The photos stimulated spontaneous thought, elicited personal content, and revealed the complexity of spirituality. The different areas of spirituality were shown to nourish one other. The online format of the interventions contributed to the spiritual care of older adults in social isolation and can serve as a supportive tool in palliative care settings [32].

Tucker et al [33] found that online community assets offered valuable peer support during periods of isolation. A hybrid model combining digital and face-to-face elements (video calls) was found to be beneficial for greater inclusivity. Digital community resources enhanced access and created a sense of safety and security. However, the study also noted that greater inclusivity could come at the expense of depth of support and intimacy.

In a quantitative study with qualitative components, Roy et al [29] investigated whether artistic online counseling during the COVID-19 lockdown could help interested participants reduce stress, enhance well-being, and feel more connected. Conducted at a university of the arts (the “a.l.s.o.b. project”), the study recruited participants through various channels, including social media, private networks, university mailing lists, and external partners such as post-inpatient support groups and clinics. The art therapy-orientated interventions led to significant improvements in health parameters. Participants experienced a significant reduction in current stress levels (p=.001), and improved habitual well-being, mood (including symptoms of anxiety and depression), and connectedness (each p=.001) over the four-week period following the intervention. An increase in the aesthetic experience was also reported.

Change factor analysis

In the following overview (Table 2 [Tab. 2]), these results are assigned to common factors of OCATs, with the aim of analyzing findings across different target groups. Common factors of psychotherapy can be applied to all therapeutic formats [39]. This article uses the categorization of change factors according to Grencavage and Norcross [9]. The authors list the following common factors:

- Patient characteristics: Characteristics and behaviors, especially active help-seeking and positive therapy expectations.

- Therapist characteristics: Therapist characteristics and competencies such as appreciation, empathy, building positive therapy expectations and status as a recognized healer.

- Change processes: Therapeutic changes and intermediate steps in the patient, such as catharsis, desensitization, insight, and the development of behavioral skills.

- Treatment structure: Orientation towards a therapy theory, use of techniques/rituals, creation of a healing environment, communication (verbal and nonverbal).

- Therapy relationship: Interactional change factors such as therapeutic cooperation (therapeutic alliance) and the handling of transference processes.

The overview (Table 2 [Tab. 2]) shows similarities and differences in the framework conditions and effects of OCATs depending on the target group, particularly with regard to the common factors according to Grencavage and Norcross [9].

From an artistic-therapeutic perspective, specific arts therapies common factors can also be extracted from the identified change processes and the treatment structure, following the categorization by Grencavage and Norcross [9] (see Table 2 [Tab. 2]) [12], [16], [40]. As shown in the artistic-therapeutic literature, the specific change factors include the stimulation of the ability to symbolize and imagine, the promotion of a sense of community and self-efficacy through creative work in a group, opportunities for communication through a medium of expression, the stimulation of creativity, play, and regression [12], [16], [20], and art as beauty and as a form of authentic expression aimed at integration/body-mind unity/emotion regulation [40].

In the studies reviewed here, the results particularly highlighted the specific change factors of problem solving through artistic activity, social interaction and the creation of a sense of community, positive experiences with art among people with disabilities, the promotion of emotional experience and the expression of joy in creating within health promotion programs.

Within the framework of the general impact factor "treatment structure", the studies reported positive effects specifically linked to artistic interventions. The use of photo collages, the presentation of digital photos as projective visual stimuli, and the creation of self-portraits were emphasized as particularly helpful in achieving therapeutic goals. The provision of artistic materials, the reduction of materials, group size, and intervention time were seen as effective strategies for simplifying organizational matters and enabling an individual approach to clients.

Discussion

This systematic review examined the conditions and effects of OCATs and counseling on different target groups.

The focus of the analysis was on findings from the most recent studies between 2021 and 2024. Following a thorough review, the database search yielded eleven studies that met the inclusion criteria. In the following section, we assign the results – analyzed by target group –, to common change factors according to Grencavage and Norcross [9] and discuss them within the framework.

As the literature and earlier research findings have shown, the digitalization of therapeutic work brings a range of opportunities and challenges that produce varied effects on both patients and therapists. These effects influence change processes, treatment structure, and the therapeutic relationship. The findings of previous studies were largely confirmed by analysis of the most recent studies. In this review, the patient and client perspectives were included to a greater extent. The need to investigate the client perspective, in contrast to the therapist perspective, is explicitly emphasized in the review by Zubala et al [1].

Patient characteristics

From the perspective of arts therapists [2], [30], [34], [[35], [36], digital therapy formats offer patients a sense of security and less social stigmatization [30], [34]. Access to therapy is made easier and family members can be more readily integrated. Mental acceptance of new technologies leads to a greater willingness to adapt, and differences in artistic ability are less visible. A practical report by Biro-Hannah [41] also showed that, after several months of weekly online group sessions, clients rated the opportunity to express negative feelings in a protected environment positively.

It was observed that patients in clinical follow-up care had to take more responsibility for their personal workspace and the artistic materials in the online format compared to face-to-face settings. Providing the necessary materials in advance could help support participants in this respect [2].

A certain level of online affinity is particularly helpful for older adults and people with disabilities [37], [38] to overcome challenges such as the digital divide – i.e., barriers and deficits in digital competence. In the review by Turcotte et al. [4] on participation in preventive health programs for people over the age of 65, various barriers are identified, including the expectation of high effort with low effectiveness, difficulty using new technologies, and sensory impairments. The study by Keisari et al. [35] showed that support from family members or other companions can help overcome these barriers. Overall, this target group reported a feeling of more protected access and greater inclusivity, as their artworks were initially not visible to others. However, some negative effects must also be considered. For example, Zubala et al. [1] identified drawbacks to inclusivity, such as negative impacts on the quality of the relationship, resulting in a reduction in intimacy and in opportunities for meaningful contact [33].

Therapist characteristics

As analysis of the studies shows, therapists gained expanded diagnostic possibilities by observing aspects of the patient’s private environment and benefited from increased creativity and flexibility through the use of new media [34]. This contributed to personal growth and the experience of creative self-efficacy [30], [31], [32]. Psychological support was seen as desirable, while specific training and the development of new ethical guidelines are considered necessary [31].

In online therapy – especially in counseling older adults and people with disabilities [37], [38] – a direct, personalized approach to participants emerged as an essential element in fostering a sense of connection. Involving family members was seen as beneficial. A high degree of flexibility in adapting programs to the needs of these target groups was necessary to actively support and sustain group cohesion. Turcotte et al. [4] emphasized these elements as key "facilitators" in working with older adults.

Change processes

Therapists identified several key aspects, including the promotion of personal creativity and self-efficacy through more flexible treatment, the development of new treatment techniques, and the processing of losses caused related to the pandemic [35]. The reorientation of treatment modalities offered an opportunity for personal growth and the experience of creative self-efficacy. At the same time, however, therapists also experienced loss due to the pandemic – specifically, the loss of the familiar treatment formats and physical spaces when working with clients - which led to some skepticism towards online formats. This experience of loss aligns with findings from other studies on the pandemic’s impact on the mental health of creative arts therapists [42], [43].

On the other hand, a survey by Choudhry and Keane [44] of American art therapy practitioners and students, conducted shortly after the start of the lockdown, confirmed many of the positive impressions identified in this review. For example, 76% of therapists reported that using online formats became easier with continued use, and 27% were already conducting therapeutic video sessions by May 2020, shortly after the onset of the pandemic.

Creative arts therapies are especially valuable for clients who have difficulty expressing themselves with words alone [45]. It can therefore be assumed that individuals with intellectual disabilities benefit particularly from this form of therapy. This target group also has an increased need for social interaction and community. The findings of Lewchuk et al. [37] and Taylor et al. [38] make clear that these needs could also be met through online therapy during the coronavirus pandemic. Clients reported an enhanced sense of identity and collective efficacy. They were able to gain positive and new experiences through artistic activity [37]. Potash et al. [46] likewise reported, just a few weeks after the start of the pandemic, that artistic activity helps restore a sense of control, opens new perspectives, and fosters connection and communication.

In the study with older adults [31], [32], researchers found that emotional experiences could be promoted through artistic activity. Artistic creation gave rise to joy while also supporting the processing of life experiences. A connection with oneself, the environment and the transcendental emerged. As the literature shows, arts therapies interventions strongly influence emotion regulation and stress reduction [13], [18], [47], [48], [49], [50].

In the art therapy counseling project (“a.l.s.o.b. project”) at a university of the arts, which aimed to promote health, researchers observed a significant reduction in stress, improved mood, habitual well-being, and connectedness, as well as an enhanced aesthetic experience among clients who voluntarily enrolled in this salutogenetic program [29], [51]. Rankanen [52] also found that 98 % of clients reported a positive improvement in their mental health, 82% observed positive effects on their social relationships, and 67% noted improvements in physical health.

Another study investigated the relationship between health promotion and art therapy in clients suffering from burnout and found a significant increase in both physical and mental well-being after a single art therapy project day [11], [20]. The results of the present review regarding the common factor “change processes” were further supported by studies and case reports that focusing specifically on experiences with online therapies. For example, Kaimal et al. [53] reported positive emotions, play and exploration, new learning experiences, and problem solving as outcomes of their qualitative study on art therapy in virtual reality (VR). VR was found to have the potential to enhance mental health and well-being through creativity, expanded imagination, interactivity, and problem solving. Participants in online workshops led by Biro-Hannah [41] also described several positive effects, including feelings of happiness, joy, fulfilment, satisfaction, freedom, and relaxation.

Treatment structure

The results related to this common change factor are especially helpful in addressing the framework conditions of online arts therapies. The artistic modalities provide additional opportunities for self-exploration and expression within a therapeutic relationship [36], [45], [53], using tangible art materials, music, embodied movements and gestures, and enacted or written characters and stories. As a result, the shift to online formats requires profession-specific adaptations that reflect the unique characteristics of CATs practice [30]. The study by Ganter-Argast and Bocksch [2] specifically addressed the changed framework conditions of online therapy. According to their results, adapting to the digital format requires taking greater personal responsibility by participants. Clients must set up their own personal workspace. Sending materials in advance appears beneficial. Reducing the quantity of materials and limiting the number of participants were recommended as ways of simplifying the process, improving the ability to address participants individually, and giving preference to using the visual arts materials, which are more easily managed independently. Material exchange processes were generally more complicated and called for in-depth knowledge of the technical possibilities of the online medium. Working in small groups and on individual topics is feasible, and shorter design units than in face-to-face formats (20–30 minutes) were preferred to allow questions and emotions to be clarified quickly. A combination of digital and in-person sessions, along with flexible program design, proved helpful – especially when supported by technical facilitation. Antwerpen et al. [6] also discussed specific methodological and conceptual requirements for online therapy, which should be established in advance. These include a consistent review of technical capabilities, email communication with general information about access and procedure, use of video settings, and the creation of a protected framework.

When designing interventions, therapists should aim to integrate as much “three-dimensionality” as possible into online therapy – for example, through “body pauses” that encourage clients to stand and move away from the screen, or mindfulness exercises involving found (natural) objects that can be perceived through all the senses [2]. Interventions such as self-portraits, digital photo presentations as projective visual stimuli, and digital photo collages viable options [32], with a hybrid structure (including additional video calls) being particularly useful for people with disabilities [38].

Therapy relationship

Previous research has encouragingly suggested that the therapeutic alliance in verbal psychotherapies can be successfully replicated in an online environment [54]. However, in art therapy, the impact of technology extends beyond the client-therapist relationship to include the triangular relationship involving the artwork. Understanding how digital tools affect the dynamics of this triangular relationship – and their place within it – appears fundamental to increasing art therapists' confidence in integrating digital art media into sessions [1]. One particular challenge discussed in online therapy programs is the so-called “eye contact dilemma” [55]. Eye contact is essential for building a therapeutic relationship, yet direct eye contact is difficult to establish in a standard video counseling setting. However, the issue and its potential negative consequences therapeutic success were not observed in the study by Ganter-Argast and Bocksch [2] on online art therapy in aftercare. On the contrary, they found that it was possible to work on individual topics in a process-orientated way. In another study, therapists introduced the concept of the “four-sided reflection mirror” [36], referring to a new relationship structure in which both therapist and client see themselves and each other on the screen. It is possible that this configuration helps compensate for the possible drawbacks of the lack of direct eye contact.

Digital therapy allows clients to maintain greater distance and encourages more verbal communication, while making nonverbal communication more difficult. Smaller group sizes permit a more direct approach than in face-to-face formats, resulting in improved group dynamics, heightened attention, and greater connectedness [2]. Greater customization to individual clients' needs is required to ensure safe interactions with therapists, even if increased inclusivity may reduce intimacy [33], [38]. In a study by Marmarosh et al. [56], clients reported higher levels of trust in telegroups after the pandemic than before. They formed bonds with the instructor more quickly than with fellow online group members. As a result, the facilitator plays a key role in initiating and maintaining relationships by actively fostering group connectedness [29], [51].

Limitations

The study selection focused on the past five years, primarily during the time of the coronavirus pandemic, the expectation being that a particularly large number of online therapies would have been conducted during this period and that more study results would be available. At the same time, the question arises as to the transferability of these findings for non-pandemic contexts. For example, participants may have been especially motivated during the pandemic due to the lack of face-to-face programs. However, earlier studies conducted during non-pandemic times showed that a therapeutic alliance can be very effectively established in online settings [54].

In terms of research design, most studies were qualitative in nature and involved relatively small sample sizes. Another limitation of this review is the difficulty in comparing studies due to differences in conditions such as age, diagnosis, nationality, therapy duration, and the specific type of art-based interventions used (each involving different combinations of artistic activities, and in some cases, other methods such as mindfulness-based art therapy). Nonetheless, the included studies provided valuable insights into the state of mind of various target groups, contributing to the research question.

Conclusion

This systematic literature review highlights the considerable importance of OCATs and counseling, particularly for individuals who require therapeutic support under special circumstances. These include barriers related to geography, time, personality, situation, or illness that prevent in-person access to therapeutic services. As the selected studies have shown, these populations may include patients in clinical aftercare, very elderly individuals accompanied by family members, people with disabilities receiving support, and recipients of health-promoting interventions in community or university settings.

For further research, studies with both the same and additional target groups would be helpful in systematically analyzing existing findings using predefined evaluation criteria. It would also be worth investigating which target groups are less suited – or not at all – for online therapies. For example, the study by Shaw [57] with girls suffering from anorexia found that the online setting, in which they could see and be seen, caused significant distress and at times became unbearable for them.

Further investigation is needed to assess the suitability of online formats for children and adolescents, including the specific framework conditions required and the effects that can be achieved with various creative arts therapies methods. Regarding research design, it would be beneficial to conduct more quantitative or mixed-method studies in addition to qualitative research – studies that span longer periods and ideally include follow-up phases to measure changes in behavioral health parameters, both current and habitual. In terms of developing interventions, continued attention should be given to the opportunities and necessary adaptations required for online settings, and these should be increasingly documented for use by practitioners.

A comprehensive integration of content on online therapy into modules of creative arts therapies training and further education – covering specific framework conditions, interventions, effects and ethical requirements – appears necessary. Even though the online setting cannot offer the same possibilities for artistic expression and mutual perception between therapist and client as face-to-face therapy due to physical distance, online arts counseling represents an important alternative under certain conditions. To summarize, digital therapy presents both significant benefits and challenges that must be carefully addressed if the best possible therapeutic outcomes for various patient groups are to be attained.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ORCID

References

[1] Zubala A, Kennell N, Hackett S. Art Therapy in the Digital World: An Integrative Review of Current Practice and Future Directions. Front Psychol. 2021;12:595536. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.600070[2] Ganter-Argast C, Bocksch C. Onlinebasierte, ambulante Kunsttherapiegruppe. Psychotherapie. 2023;68(4):262-70. DOI: 10.1007/s00278-023-00671-9

[3] Mattson DC. Usability assessment of a mobile app for art therapy. Arts Psychother. 2015;43:1-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2015.02.005

[4] Turcotte S, Bouchard C, Rousseau J, DeBroux Leduc R, Bier N, Kairy D, et al. Factors influencing older adults' participation in telehealth interventions for primary prevention and health promotion – A rapid review. Australas J Ageing. 2023. DOI: 10.1111/ajag.13244

[5] Malchiodi CA. Handbook of Art Therapy. New York: Guilford; 2011.

[6] Antwerpen L, del Palacio Lorenzo A, Masuch J, Brons S, Gosch M, Singler K. Online-Kunsttherapie in Zeiten von Corona? Eine Darstellung digitaler Kunsttherapie am Beispiel Spanien. GMS J Art Ther. 2023;5:Doc01. DOI: 10.3205/jat000029

[7] Tabaei S. Challenges and Benefits of Tele-therapy and Using Digital World in Art Therapy Practice: An Integrative Review. Com.press. 2022;5(2):60-73. Available from: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1086449

[8] Grawe K, Donati R, Bernauer F. Psychotherapie im Wandel - von der Konfession zur Profession. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1994.

[9] Grencavage LM, Norcross JC. Where Are the Commonalities Among the Therapeutic Common Factors? Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1990;21(5):372-8.

[10] Koch SC. Arts and Health: Active factors and a theory framework of embodied aesthetics. Arts Psychother. 2017;54:85-91.

[11] Oepen R, Gruber H. Ein kunsttherapeutischer Projekttag zur Gesundheitsförderung bei Klienten aus Burnout-Selbsthilfegruppen - eine explorative Studie. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2014;64(7):268-74. DOI: 10.1055/s-0033-1358725

[12] Oepen R. Kunsttherapie zur Steigerung des Wohlbefindens in Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung. Berlin: Dr. Hans-Jürgen Brandt EB-Verlag e.K..

[13] Fancourt D, Finn S. What Is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review. Geneva: WHO Press; 2019.

[14] Lücke S. Tiefenpsychologisch fundierte Kunsttherapie in der Behandlung tramabedingter Störungen. In: von Spreti F, editor. Kunsttherapie bei psychischen Störungen. München: Urban & Fischer; 2005. p. 140-51.

[15] Killick K, Schaverien J. Art, Psychotherapy and Psychosis. London and New York: Routledge; 1997.

[16] Gruber H. Wirkfaktoren in den Künstlerischen Therapien – Was wissen wir und wie lässt sich das untersuchen? Psychol Med. 2008;19:13ff.

[17] Riedel I, Henzler C. Maltherapie: Eine Einführung auf der Basis der analytischen Psychologie von C. G. Jung. Stuttgart: Kreuz; 2004.

[18] Gruber H, Oepen R. Emotion regulation strategies and effects in art-making: A narrative synthesis. Arts Psychother. 2018;59:65-74. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2017.12.006

[19] Koch SC, Weidinger-von der Recke B. Traumatised refugees: An integrated dance and verbal therapy approach. Arts Psychother. 2009;36(5):289-96. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2009.07.002

[20] Oepen R, Gruber H. Kunsttherapeutische Interventionen bei Burnout in Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung. Musik Tanz Kunstther. 2012;23(3):117-33.

[21] Machi LA, McEvoy BT. The literature review: Six steps to success. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Corwin; 2016.

[22] Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Med. 2009;6(7):1-6. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

[23] Al-Nawas B, Baulig C, Krummenauer F. Von der Übersichtsarbeit zur Metaanalyze - Möglichkeiten und Risiken. Z Zahnärztl Impl. 2010;26:400-4.

[24] Huang X, Huang X, Lin J, Demner-Fushman D. Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006;2006:359-63.

[25] Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91-108. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

[26] National Center for Biotechnology Information. Review Literature as Topic; 2008 [cited 2024 Sep 4]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/?term=Review%20literature

[27] Edwards J, Kaimal G. Using meta-synthesis to support application of qualitative methods findings in practice: A discussion of meta-ethnography, narrative synthesis, and critical interpretive synthesis. Arts Psychother. 2016;51:30-5.

[28] Machado CB. The screen as a meeting point – reflections from Argentina on the practice of online dance movement therapy during the global COVID-19 pandemic. GMS J Art Ther. 2021;3:Doc03. DOI: 10.3205/jat000012

[29] Roy C, Paul E, Rolff H, Koch SC. a.l.s.o.b. – Ein Forschungsprojekt zur Wirksamkeit künstlerischer Onlinebegleitung während des Lockdowns 2021. In: Masuch J, Singler K, editors. Kunsttherapie - Chancen und Herausforderungen der Forschung. 1st ed. Frankfurt am Main: Mabuse-Verlag; 2023. p. 169-72.

[30] Feniger-Schaal R, Orkibi H, Keisari S, Sajnani NL, Butler JD. Shifting to tele-creative arts therapies during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international study on helpful and challenging factors. Arts Psychother. 2022;78:101898. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2022.101898

[31] Keisari S, Piol S, Elkarif T, Mola G, Testoni I. Crafting Life Stories in Photocollage: An Online Creative Art-Based Intervention for Older Adults. Behav Sci (Basel). 2021;12(1). DOI: 10.3390/bs12010001

[32] Keisari S, Piol S, Orkibi H, Elkarif T, Mola G, Testoni I. Spirituality During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Creative Arts Intervention With Photocollages for Older Adults in Italy and Israel. Front Psychol. 2022;13:897158. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.897158

[33] Tucker I, Easton K, Prestwood R. Digital community assets: Investigating the impact of online engagement with arts and peer support groups on mental health during COVID-19. Sociol Health Illn. 2023;45(3):666-83. DOI: 10.1111/1467-9566.13620

[34] Dixon M, Gómez-Carlier N, Powell S, El-Halawani M, Weber AS. Art Therapy Service Provision during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). QScience Connect. 2022;2022(3). DOI: 10.5339/connect.2022.medhumconf.32

[35] Keisari S, Feniger-Schaal R, Butler JD, Sajnani N, Golan N, Orkibi H. Loss, adaptation and growth: The experiences of creative arts therapists during the Covid-19 pandemic. Arts Psychother. 2023;82:101983. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2022.101983

[36] Shamri-Zeevi L, Katz A. The four-sided reflecting mirror: art therapists’ self-portraits as testimony to coping with the challenges of online art therapy. Int J Art Ther. 2022;27(3):112-20. DOI: 10.1080/17454832.2021.2001024

[37] Lewchuk DR, D’Amico M, Timm-Bottos J. Digital Footprints: Exploring Digital Inclusion in Adults With Developmental Disabilities. Can J Art Ther. 2021;34(2):52-62. DOI: 10.1080/26907240.2021.1982171

[38] Taylor ER, Estevao C, Jarrett L, Woods A, Crane N, Fancourt D, et al. Experiences of acquired brain injury survivors participating in online and hybrid performance arts programmes: an ethnographic study. Arts Health. 2024;16(2):189-205. DOI: 10.1080/17533015.2023.2226697

[39] Pfammatter M, Junghan UM, Tschacher W. Allgemeine Wirkfaktoren der Psychotherapie: Konzepte, Widersprüche und eine Synthese. Psychotherapie. 2012;17(1):17-31.

[40] Koch SC. Was hilft, was wirkt? Z Sportpsychol. 2017;24(2):40-53. DOI: 10.1026/1612-5010/a000191

[41] Biro-Hannah E. Community adult mental health: mitigating the impact of Covid-19 through online art therapy. Int J Art Ther. 2021;26(3):96-103. DOI: 10.1080/17454832.2021.1894192

[42] Atsmon A, Pendzik S. The clinical use of digital resources in drama therapy: An exploratory study of well-established practitioners. Drama Ther Rev. 2020;6(1):7-26. DOI: 10.1386/dtr000131

[43] Gereb Valachine Z, Karsai SA, Dancsik A, de Oliveira Negrao R, Fitos MM, Cserjesi R. Online self-help art therapy-based tasks during COVID-19: Qualitative study. Artelor Ther. 2021:1-7.

[44] Choudhry R, Keane C. Art Therapy During A Mental Health Crisis: Coronavirus Pandemic Impact Report. Arlington, VA: American Art Therapy Association; 2020. Available from: https://arttherapy.org/blog-coronavirus-impact-report/

[45] Orkibi H, Ben-Eliyahu A, Reiter-Palmon R, Testoni I, Biancalani G, Murugavel V, et al. Creative adaptability and emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international study. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. 2024;18(2):245-55. DOI: 10.1037/aca0000445

[46] Potash JS, Kalmanowitz D, Fung I, Anand SA, Miller GM. Art Therapy in Pandemics: Lessons for COVID-19. Art Ther. 2020;37(2):105-7. DOI: 10.1080/07421656.2020.1754047

[47] Boehm K, Cramer H, Staroszynski T, Ostermann T. Arts therapies for anxiety, depression, and quality of life in breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:103297. DOI: 10.1155/2014/103297

[48] Dannecker K, Herrmann U. Warum Kunst? Über das Bedürfnis Kunst zu schaffen. Berlin: MWV Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 2017.

[49] Martin L, Oepen R, Bauer K, Nottensteiner A, Mergheim K, Gruber H, et al. Creative Arts Interventions for Stress Management and Prevention - A Systematic Review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018;8(2). DOI: 10.3390/bs8020028

[50] Oepen R, Gruber H. Art-based interventions and art therapy to promote health of migrant populations - a systematic literature review of current research. Arts Health. 2024;16(3):266-84. DOI: 10.1080/17533015.2023.2252003

[51] Roy C, Rolff H, Paul E, Wörner A, Koch SC. Das a.l.s.o.b.-Projekt: Veränderung von Stress, Befindlichkeit, Verbundenheit und ästhetischem Erleben nach studentisch begleiteten kunstbasierten online-Gruppen während der Covid-19-Pandemie. GMS J Art Ther. 2025;7:Doc03. DOI: 10.3205/jat000043

[52] Rankanen M. Clients’ experiences of the impacts of an experiential art therapy group. Arts Psychother. 2016;50:101-10.

[53] Kaimal G, Carroll-Haskins K, Berberian M, Dougherty A, Carlton N, Ramakrishnan A. Virtual Reality in Art Therapy: A Pilot Qualitative Study of the Novel Medium and Implications for Practice. Art Ther. 2020;37(1):16-24. DOI: 10.1080/07421656.2019.1659662

[54] Sucala M, Schnur JB, Constantino MJ, Miller SJ, Brackman EH, Montgomery GH. The therapeutic relationship in e-therapy for mental health: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(4):e110. DOI: 10.2196/jmir.2084

[55] Engelhardt E, Engels S. Einführung in die Methoden der Videoberatung. Fachzeitschrift für Onlineberatung und computervermittelte Kommunikation. 2021;17(1):5-19. Available from: https://www.e-beratungsjournal.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/engelhardt_engels.pdf

[56] Marmarosh CL, Robelo A, Solorio A, Xing F. Miles Away. In: Weinberg H, Rolnick A, Leighton A, editors. The Virtual Group Therapy Circle. New York: Routledge; 2023. p. 40-51.

[57] Shaw L. ‘Don’t look!’ An online art therapy group for adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa. Int J Art Ther. 2020;25(4):211-7. DOI: 10.1080/17454832.2020.1845757