Analysis of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens (MRGN) in different areas of the healthcare system and their significance in the outpatient sector

Cosima Berdin 1Tobias Kaspers 1

Barbara Gärtner 1,2

Alexander Halfmann 1

Fabian K. Berger 3

Nina Walzer 1

Sören L. Becker 1

Sophie Schneitler 4

1 Institute of Medical Microbiology and Hygiene, Saarland University Medical Center, Homburg, Germany

2 National Reference Center for Clostridioides difficile, Homburg – Münster – Coesfeld, Germany

3 Institute of Virology, Saarland University Medical Center, Homburg/Saar, Germany

4 Institute for Medical Microbiology, Immunology and Hygiene, University Hospital Cologne, Germany

Abstract

Given the global threat of increasing antibiotic resistance, risk factor detection of multi-resistant pathogens is particularly important. This is complicated by different definitions, using the international extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) definition and the German definition of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens (MRGN). Although the MRGN definition was primarily introduced for hospital hygiene measures, it is often used in outpatient or semi-inpatient areas. Due to the increasing numbers of outpatient treatments of the healthcare system, corresponding data is necessary for specific hygiene regulations.

This study provides MRGN and ESBL data based on a stool examination and a questionnaire evaluation in the period 07/2021–03/2022 of 231 outpatients of Saarland University Medical Center before traveling abroad.

There was a 3MRGN prevalence of 2.6% with five Escherichia coli and one Klebsiella pneumoniae and an ESBL prevalence of 5.6% with 13 ESBL Escherichia coli, four of which could also be classified as 3MRGN. These prevalences were compared with MRGN/ESBL prevalences in PubMed and Google Scholar in different areas of the German healthcare system in the period 2013–2024 at the federal state level. The selective literature search revealed geographical differences and missing prevalence data depending on the healthcare sector (outpatient/inpatient) and federal state.

Resistance data is often evaluated according to international standards, i.e. according to the ESBL definition. Outpatient MRGN prevalences are hardly known despite the increasing numbers of outpatients of the healthcare system. Due to the scarcity of outpatient data, our study from a travel medicine clinic provides interesting epidemiological data that should be considered in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords

drug resistance, COVID-19, ambulatory care, beta-lactam resistance, MDR

Introduction

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the increase in antibiotic resistance is one of the ten greatest global threats to public health [1], with a WHO list from 2017 highlighting the risk posed by Gram-negative pathogens in particular [2]. The risk factors for acquiring resistance are multidimensional and the prevalence varies geographically [3]. The “One Health” concept highlights the connection between humans, animals and the environment, with data from human and veterinary medicine as well as environmental studies showing that the use of antibiotics leads to the selection of multi-resistant pathogens [4]. A 2015 report showed that outpatient prescriptions accounted for about 85% of overall antibiotic consumption in human medicine in Germany [5]. Regionally, a diverging risk factor can be assumed, as the use of antibiotics varies in different areas, including agriculture [6], [7].

In the USA, warnings were issued about increasing resistance during the COVID-19 pandemic [8], but Werner et al. reported a decrease in multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens (MRGN) during the pandemic years in German intensive care units following rising colonisation rates until 2019 [4]. Further epidemiological data focusing on MRGN in other areas of the healthcare system, such as outpatient care, particularly with regard to undetected colonisation, are of great importance for the development of differentiated hygiene measures.

There are various classifications for Gram-negative pathogens. In German-speaking countries, the MRGN classification of the Commission for Hospital Hygiene and Infection Prevention (KRINKO) at the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) [9] is primarily used, whereas internationally, extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) in particular are evaluated.

The RKI defines ESBL as resistance to cefpodoxime and cefotaxime and/or ceftazidime, which can be inhibited by beta-lactamase inhibitors such as sulbactam or clavulanic acid (MICcephalosporin/MICcephalosporin+inhibitor≥8) [10]. Beta-lactamases can hydrolyse the beta-lactam ring of beta-lactam antibiotics and prevent binding to the transpeptidase (penicillin-binding protein) of the bacterial cell wall [11]. Depending on their hydrolysis capacity, there are different types such as penicillinases, cephalosporinases and carbapenemases [12].

The MRGN definition is based on in vitro resistance to key substances from four antibiotic groups (piperacillin (acylureidopenicillins), ceftazidime and/or cefotaxime (3rd/4th generation cephalosporins), imipenem and/or meropenem (carbapenems) and ciprofloxacin (fluoroquinolones)) [9]. Resistance to three or four of the key substances is described as 3MRGN and 4MRGN [9]. Carbapenem resistance in 4MRGN can arise in addition to AmpC or ESBL formation and porin loss due to carbapenemases [9]. It is used in particular in hospitals for risk assessment, determining hygiene measures such as isolation or basic hygiene (e.g. surface disinfection) and establishing screening guidelines [9].

Inpatient data is primarily used to derive hygiene measures, which may be due, among other things, to the available data collection. Comparing data in inpatient and outpatient contexts is difficult due to different risk factors and patient groups. This is illustrated by studies on colonisation with Gram-negative pathogens during foreign travel [13], [14], [15].

The increasing shift towards outpatient care requires a better understanding of MRGN occurrence in the outpatient sector in order to develop risk-stratified hygiene measures. The aim of this study is to present outpatient MRGN data from one federal state and compare it with other published data from various areas of the German healthcare system. Based on this survey, the various outpatient regional MRGN resistance patterns will be analysed, highlighting the difficulties of a uniform survey using the example of classification patterns, and measures in the outpatient sector will be discussed.

Method

Resistance data were collected in the Travel and Tropical Medicine Outpatient Clinic at Saarland University Hospital from travellers who required a COVID-19 PCR test before travelling abroad between 1 July 2021 and 15 March 2022 using an MRGN risk questionnaire and a stool test before travel.

The study was conducted with the approval of the responsible ethics committee (Saarland Medical Association, 205/21), in accordance with national law and the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided their consent for anonymous data collection.

The questionnaire consisted of 30 multiple-choice questions and three open-ended questions for general, personal information about future and past travel destinations and the duration of travel. To create the questionnaire, MRGN and ESBL risk factors in travellers from previous studies were evaluated and supplemented with additional questions focusing on MRGN (Table 1 [Tab. 1]). The questionnaire consisted of basic demographic questions (including age) as well as questions about medical history and travel behaviour.

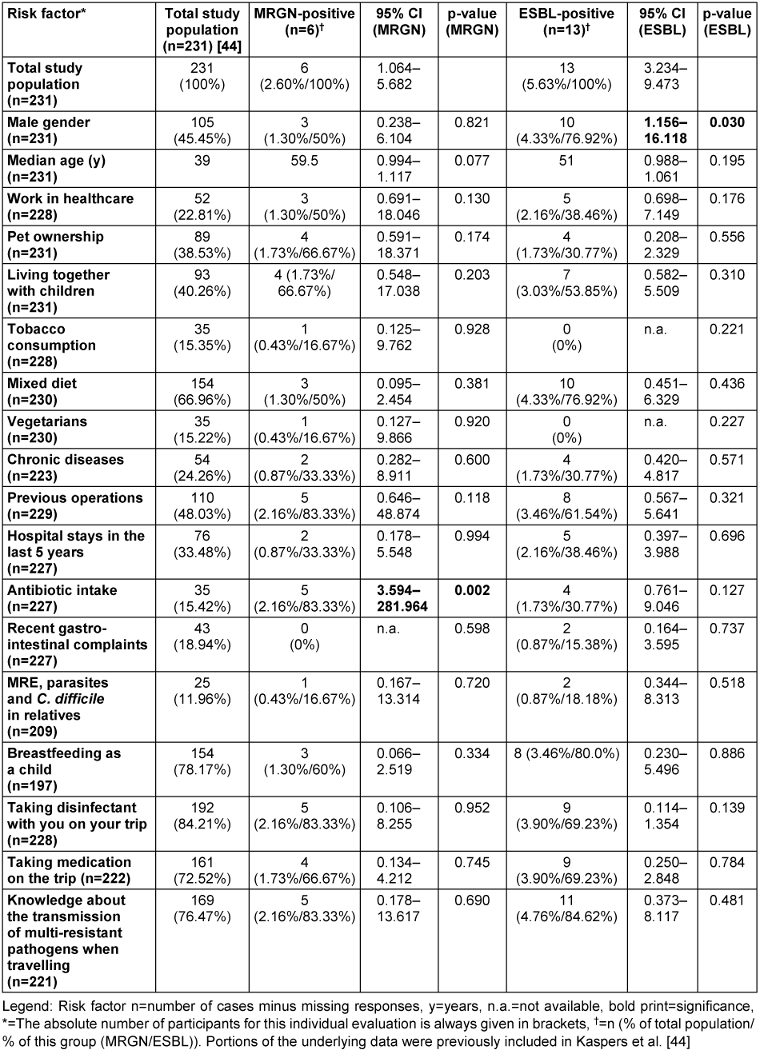

Table 1: Comparison of individual risk factors analysed for all 3MRGN (five E. coli + 1 Klebsiella pneumoniae) and all ESBL E. coli with illustration of the total cohort

The stool sample was examined using chromogenic ESBL agar (CHROMagar ESBL/VRE ready plates; Mast Diagnostica). Growth was distinguished by different staining patterns and the morphology of the pathogens to identify different species. Relevant colonies were identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (Bruker, Bremen). Sensitivity testing was performed using the MicroScan autoSCAN-4 system (Beckman Coulter) with a Neg multidrug-resistant MIC 1 (NMDR1) panel (Beckman Coulter). Evaluation was performed according to EUCAST 11.0 (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing) criteria. In cases of technical measurement uncertainty, verification was performed using an epsilometer test (MIC Test Strips, Liofilchem®). An ESBL confirmation test was performed using the disc diffusion method “AmpC and ESBL Detection Set” (MASTDISCS® Combi) if ESBL could not be reliably confirmed in the MicroScan autoSCAN-4 system.

The statistical analysis of group differences was performed using the SPSS programme (version 29.0 (IBM)) by means of logistic regression analysis, whereby odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values were calculated. P-values were evaluated with a significance level of a=0.5% and tested bilaterally. If the cell counts were too small, the p-values of categorical data were determined using Fisher’s exact test. MRGN/ESBL colonisation was classified as a dependent variable in the regression analysis and the risk factors to be investigated were classified as coefficients (0=no, 1=yes). The 95% CI of prevalence was calculated using Stata Version 16.1 (Stata Corp.) with Agresti-Coull confidence intervals [16].

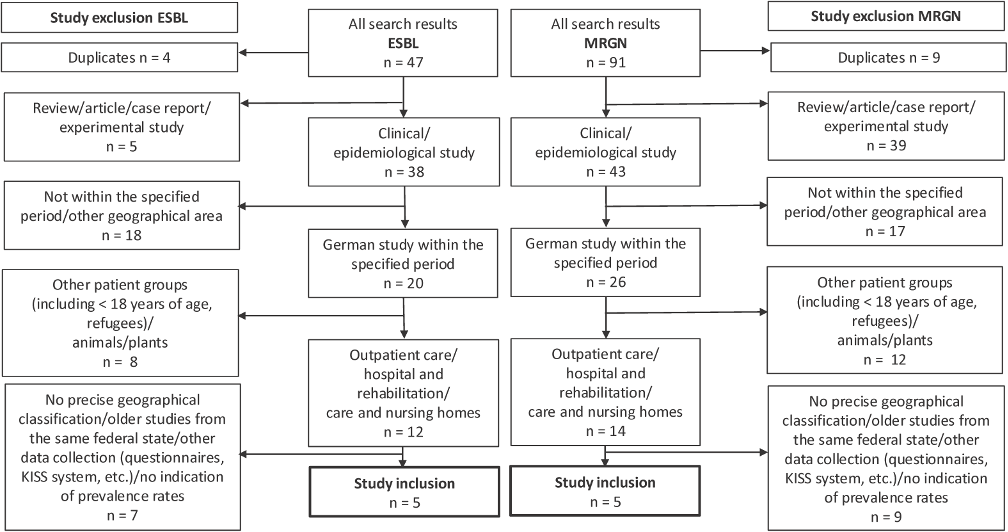

The comparative analysis was performed using selective literature searches in PubMed and Google Scholar (Figure 1 [Fig. 1] and Figure 2 [Fig. 2]). The search parameters “ESBL Germany Travel” and “MRGN” and the filter “Humans” were used in PubMed and supplemented by a title search with the keywords “MRGN” or “ESBL Germany” in Google Scholar. Studies were searched for between 2013 and 2024 that examined geographically clearly assignable data on German ESBL/MRGN prevalences and could be assigned to the study settings outpatient/travellers, hospital/rehabilitation or nursing and care homes. Only studies that examined stool samples and/or (peri-)anal/rectal swabs from adult study participants were included. Studies were excluded if no specific geographical assignment to a federal state could be made. This did not apply to studies from the Rhine-Main area, which were assigned to the federal state of Hesse. If study data from the same area and federal state were available, the most recent study data were used. A total of twenty studies were excluded due to their focus on individual patient groups, such as refugees and pregnant women [17], [18] or agricultural workers [19]. The diagrams were created in Excel using @GeoNames, Microsoft, Tomtom (supported by Bing).

Figure 1: Flow chart of study inclusion ESBL/MRGN in the period 2013–2024

PubMed with filter “Humans”: search parameters “ESBL Germany Travel”, as of 25 June 2024 (19 results), search parameters “MRGN”, as of 7 July 2024 (45 results)

Google Scholar: search parameter “ESBL Germany” in title, as of 10 July 2024 (28 results), search parameter “MRGN” in title, as of 10 July 2024 (46 results)

Citations and patents were excluded.

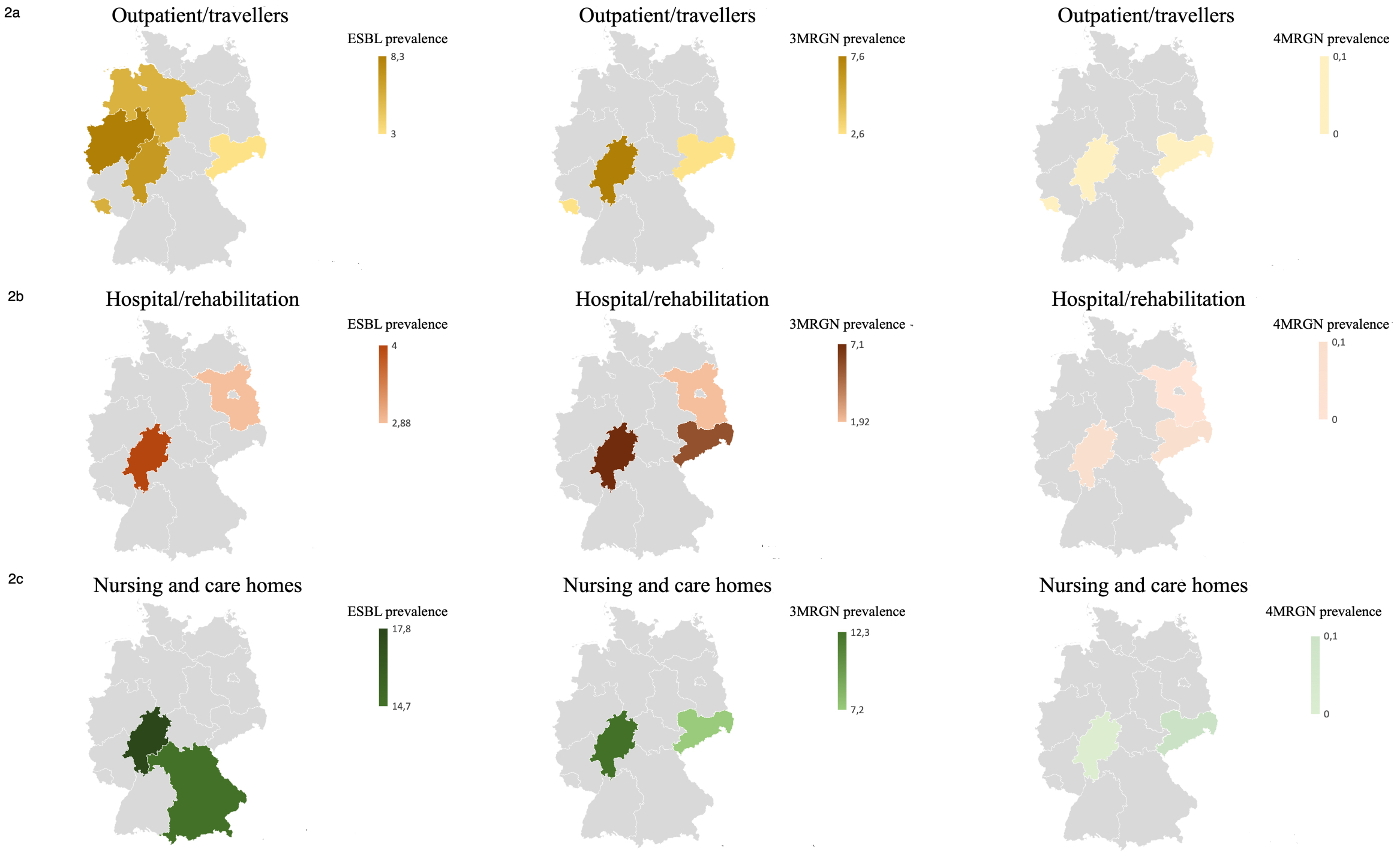

Figure 2: Consolidated figure of the literature study data on prevalences (%) of outpatient/travellers (2a), hospital/rehabilitation (2b) and nursing and care homes (2c) with illustrations of the resistance definitions ESBL (column 1), 3MRGN (column 2) and 4MRGN (column 3). The corresponding colour intensity reflects the respective evidence; if data is missing or there is no evidence of resistance for this area, grey is used as the background colour.

The following studies, which were mapped at the federal state level, were taken into account for the creation of the graphs for the data collection period 2013–2024 (authors’ details including numerical reference, data can be requested from the authors): Heudorf et al. [26]; Hogardt et al. [20]; Kiefer et al. [45]; Meurs et al. [26]; Neumann et al. [22]; Schaumburg et al. [27]; Sommer et al. [24]; Steul et al. [21]; Symanzik et al. [25]; Valenza et al. [46]

Results

The complete data set included 231 participants (380/60.79%) who planned trips lasting from one day to 280 days, predominantly female (n=126/54.5%) and with a median age of 39 [25th to 75th percentile: 27–56] (Table 1 [Tab. 1]).

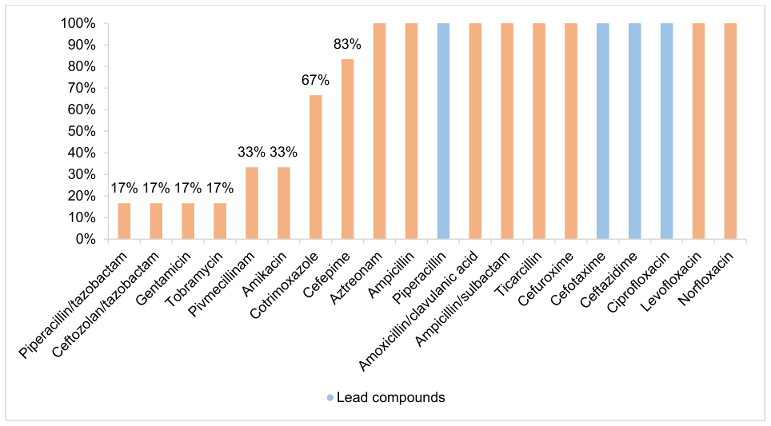

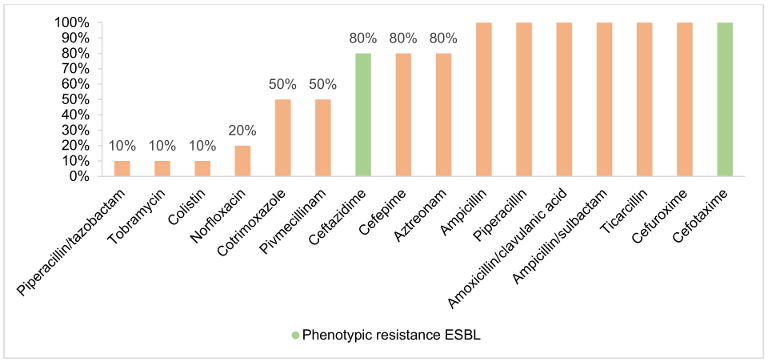

A 3MRGN prevalence of 2.60% (6/231; 95% CI 1.06–5.68) was found in the absence of 4MRGN detection (Figure 3 [Fig. 3]). Of all 3MRGN, a total of five Escherichia coli (E. coli) and one Klebsiella pneumoniae were detected. The sole significant risk factor for MRGN acquisition was antibiotic use during the previous six months (odds ratio (OR) 31.83; 95% CI 3.59–281.96; p-value 0.002). A total of 5.63% of the strains (Figure 4 [Fig. 4]), all of which were E. coli, formed ESBL (13/231; 95% CI 3.23–9.47). A significant risk factor for acquiring ESBL prior to travel was “male gender” (odds ratio: 4.32; 95% CI 1.16–16.12; p-value 0.030). Four of the ESBL-producing E. coli could also be classified as 3MRGN. The median age of the MRGN group was approximately eight years higher than in the ESBL group, without statistical significance (Table 1 [Tab. 1]). With regard to hygiene behaviour, five participants (83.33%, p-value 0.952) in the MRGN-positive group took disinfectants with them on their trip, as did nine participants (69.23%, p-value 0.139) in the ESBL-positive group (Table 1 [Tab. 1]).

Figure 3: Antibiotic resistance of MRGN (evaluation according to EUCAST)

Figure 4: Antibiotic resistance of ESBL (evaluation according to EUCAST)

A search using the search parameter “ESBL Germany” in PubMed yielded a total of 285 studies. After focusing on “EBSL Germany travel” in a study of travellers, 19 studies appeared, which were supplemented with the results from Google Scholar (n=47, Figure 1 [Fig. 1]) (as of 24 October 2024). A total of 91 studies were found when searching for MRGN prevalence (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). After applying the exclusion criteria, five ESBL studies and five MRGN studies were ultimately included (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]).

In general, there were many studies from the Rhine-Main region [20], [21], [22], [23].

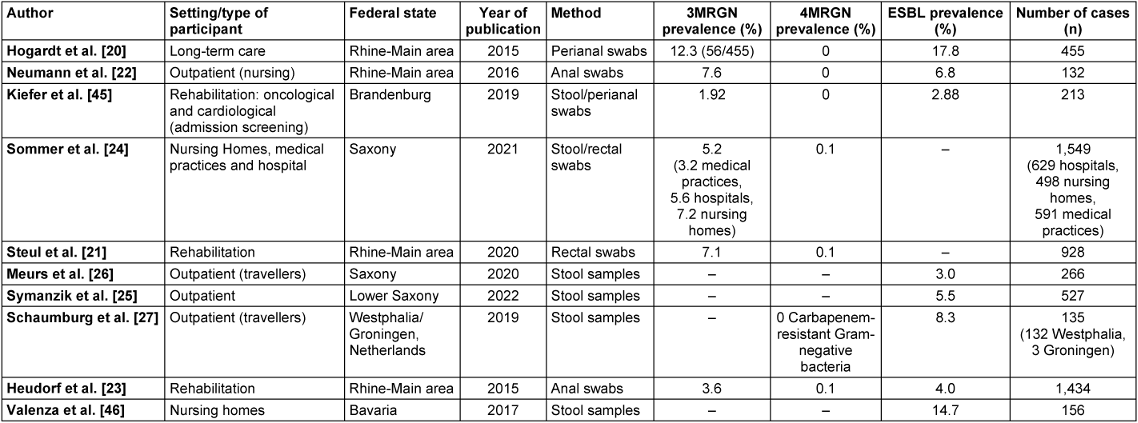

The six included studies from the field of rehabilitation and in hospitals, nursing and care homes and medical practices had varying numbers of participants for anal-/rectal swab or stool analysis (range: 156–1,549, Table 2 [Tab. 2]). Four included studies with selective data from the outpatient setting had lower case numbers (range: 132–527, Table 2 [Tab. 2]).

Table 2: Results of the literature review (areas, federal states, prevalence and case numbers). n refers to collected stool samples and perianal swabs. In some studies, n may also include results obtained from other swab types.

A literature review on the resistance situation in different populations and risk settings in various federal states revealed high 3MRGN prevalences, particularly in nursing and care homes, with 7.2% [24] in Saxony and 12.3% [20] in the Rhine-Main area (Figure 2 [Fig. 2]). Comparatively high 3MRGN prevalences were also found in hospitals and rehabilitation centres, with 7.1% [21] in the Rhine-Main area and 5.6% [24] in Saxony. In the outpatient population and among travellers, only a few studies on MRGN prevalence were included, with prevalence rates of 3.2% 3MRGN in medical practices in Saxony [24] and 7.6% 3MRGN in outpatient care services [22] in Hesse. ESBL prevalence in the outpatient setting was 5.5% ESBL Enterobacterales [25] in the outpatient population in Lower Saxony, 3.0% among travellers [26] in Saxony, 6.8% among outpatient care services in the Rhine-Main area [22] and 8.3% among travellers in Westphalia [27] (Figure 1 [Fig. 1], Table 2 [Tab. 2]).

Discussion

The establishment of national hygiene rules is dependent on regional data on the prevalence of resistance being available nationwide for decision-making purposes. In this study and literature review, resistance data was collected in Saarland and classified according to currently known national data. This revealed a lack of comprehensive geographical MRGN data, particularly in the outpatient sector. MRGN analysis is important for deriving hygiene measures and implementing preventive measures, e.g. final disinfection of the examination room [28].

The MRGN definition established in Germany and Austria is often not used due to its limited international comparability. As a result, only 19% of the data from Germany was evaluated for MRGN (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). This reduces the supraregional usability of the data collection and international comparison. At the same time, the national significance of the ESBL data is limited, as the KRINKO recommendations are based in particular on the MRGN classification [9].

The 3MRGN prevalence of 2.6% from Saarland was similar to that reported by Sommer et al. [24], which was 3.2% in a data collection from medical practices in Saxony. A higher 3MRGN prevalence of 7.6% was found in outpatient care services in Hesse [22]. The ESBL prevalence in Saarland of 5.6%, which was determined in the context of this study, was comparable to that of Symanzik et al. [25] with 5.5% in the outpatient population in Lower Saxony.

The literature review showed that MRGN prevalence in Germany was often surveyed with a focus on risk populations and structures, with higher prevalence rates in elderly care in particular, with up to 17.8% ESBL and 12.3% 3MRGN [20]. This could be due to the fact that there are more known MRGN risk factors in this sector, such as more frequent hospital contacts.

Multicentre studies often could not be assigned to specific federal states, making it impossible to assign geographical prevalence [29] and complicating the derivation of regionally adapted hygiene measures. Furthermore, it became apparent that some studies focused on selected resistance patterns, such as Rhode et al. [29] on third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales. Furthermore, there were many multicentre studies that mapped tertiary care with a specific risk profile, as these settings are characterised by more frequent high-risk procedures with lengthy hospital stays [9]. In addition, there were specific study groups, such as refugees or agricultural workers, for whom no data transfer to general prevalences could be made due to their region of origin or the divergent use of antibiotics in agriculture [6]. Individual studies also referred to a larger geographical area and not a specific federal state, such as Rodríguez-Molina et al. [30] on the greater southern Germany area. One factor that made it difficult to compare the studies was the test material, because stool samples or anal/rectal swabs were not always used; instead, data from the Hospital Infection Surveillance System (KISS) was used.

There are striking geographical differences depending on the area and federal state, and in approximately half of the federal states (including the Rhine-Main area with Bavaria, Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate), the relevant information is not available due to a lack of surveys or data publication (Figure 2 [Fig. 2]). Comprehensive data from other federal states in all of the above-mentioned areas could not be obtained from the literature. In Saarland in particular, there are few submissions from inpatient and outpatient care to the RKI’s Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance (ARS) [31], which is why the present study from a travel medicine outpatient clinic with a 3MRGN rate of 2.6% and an ESBL prevalence of 5.6% provides new data. The comparison of data from the RKI’s Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance (ARS) on MRGN in various areas is limited, as ARS data has not been evaluated in this regard since 2014 because the MRGN definition was introduced primarily to define hygiene measures [9] and not for epidemiological surveillance. The calculation of MRGN rates was based on the antibiograms of the isolates. However, as values for the defining antibiotic groups were increasingly missing, these antibiograms were increasingly unsuitable for reliable analysis (information from personal communication with the RKI). Overall, this results in a lack of data.

The lower number of cases in outpatient studies could be due, among other things, to the difficulty of recruiting study participants compared to the inpatient sector and rehabilitation. Furthermore, it must be discussed whether there was a need for data, as MRGN prevention measures and diagnostics have so far been used primarily in inpatient settings and rehabilitation. This is because contact isolation and other hygiene measures are indicated in inpatient settings depending on the area, pathogen and high-risk patients [9]. As a result of rising life expectancy, with an increase in outpatient care services and a decrease in the length of inpatient stays [32], it is all the more important to focus on the transmission of resistance in the outpatient sector and to evaluate the existing risk and derive hygiene measures. Outpatient colonisation poses a risk of resistance transmission to the inpatient sector and further spread there [10]. Nevertheless, there has been a low number of outpatient screenings in German emergency departments to date [33]. The lower MRGN admission prevalence in the case of risk-based screening compared to an analysis of all patients admitted to intensive care units suggests that there are MRGN-positive patients outside the risk groups and indicates that the defined risk factors are not specific enough [34].

In outpatient settings, there are currently no specific recommendations for colonised individuals, as hygiene measures such as isolation are often difficult to implement due to structural conditions. In future, when designing or redesigning outpatient facilities, the necessary spatial provisions for colonised patients should be taken into account (e.g. extra waiting areas, waiting times due to disinfection measures) and included in corresponding recommendations for the outpatient sector. Alternative prevention concepts that reduce resistance overall, such as national campaigns to promote hand hygiene [35], are also particularly important in the outpatient sector.

Close physical contact, including in the household [36], [37], is an important risk factor for the transmission of resistance [4] and should be considered as an outpatient hygiene measure in the population for successful implementation, in particular through regular training for high-risk patients, their relatives and staff. One simple alternative would be to introduce a buddy principle, whereby two people support each other in complying with hygiene measures, observe each other and correct each other if necessary.

It would be important to investigate such concepts prospectively in order to establish hygiene measures for risk groups on a permanent basis, especially in an environment that could become more difficult for patients from an organisational point of view with increasing outpatient health services.

Increasing MRGN prevalence [38] is caused by many factors, including travel [14], agricultural [6] and antibiotic use in human medicine [4]. In the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant decline in the overall European consumption of systemically effective antibiotics was observed, particularly in the outpatient sector [39], with an increased use of broad-spectrum and reserve antibiotics [40]. The increased implementation of hygiene measures during the COVID-19 pandemic may be a factor influencing the transmission of resistance [41] and may occur through direct or indirect contact [9]. Infection prevention, particularly through hand hygiene, is therefore of high importance and has clearly demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic that it is feasible on a population-wide basis [42]. Based on this, it was discussed that the hygiene requirements of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the use of alcohol-based hand sanitisers, could lead to lower infection rates from antibiotic-resistant bacteria [43].

In summary, it can be said that there are no comprehensive comparative studies on MRGN prevalence in the outpatient population without known risk factors. Particularly in the outpatient sector, developments cannot be reliably tracked due to limited surveillance. The available data provide interesting insights with a 3MRGN rate of 2.6% and an ESBL prevalence of 5.6%. Overall, our cohort showed a low MRGN prevalence, which could be influenced by several factors, including data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result of rising life expectancy and an increase in outpatient services in the care and health sector [32], where an increase in MRGN prevalence is to be expected, it is important to focus on detecting outpatient resistance transmission and unrecognised colonisation factors. However, due to its lower international relevance compared to ESBL, the data collected is analysed less in terms of MRGN prevalence. Following the lifting of travel restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, it can be assumed that travellers could once again play a greater role in outpatient transmission.

Risk factors such as carrying disinfectants (Table 1 [Tab. 1]) probably reflect different risk behaviour in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic than before the pandemic. Carrying disinfectants suggests an increased awareness of hygiene. On the one hand, this limits the comparability of the data presented in the literature review, but on the other hand, the data are particularly interesting with regard to this influencing factor, as they show that patients implement appropriate behaviour when given appropriate training and provided with hygiene materials.

The comparability of data from the literature review is limited by the fact that study criteria are not always identical, particularly due to differences in study timing, settings and methods (especially different resistance tests), so that although nursing homes could be classified as outpatient settings, they were considered separately due to MRGN risk factors in order to minimise potential consumption. This highlights the importance of clear guidelines for MRGN testing in the geographical setting.

The exclusion rate of the screening performed may have been influenced by the effort involved in collecting stool samples. In addition, study inclusion was made more difficult by COVID-19 travel restrictions. Study recruitment in the travel clinic may reflect specific risk behaviour for MRGN acquisition, although this should be considered with the limitation that all travellers required a SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. This also resulted in travellers presenting who would not normally visit a travel medicine clinic and who could therefore be assumed to have lower prevention behaviour. The risk factors analysed in this study may be distorted by the low MRGN and ESBL prevalences and were somewhat lower compared to similar study settings (Figure 2 [Fig. 2]), which may have been influenced by COVID-19 measures.

Conclusion

Due to its international relevance, ESBL data is often collected and published in Germany in an outpatient setting instead of MRGN data. There is only limited epidemiological data available on MRGN prevalence in all healthcare structures and federal states, which is why this study, with an outpatient study population in Saarland, represents previously insufficiently known resistance data in a regional comparison and shows that hygiene implications could arise due to internationally varying definitions of resistance. The increasing structural shift towards outpatient care in the healthcare system and the growing relevance of MRGN highlight the need for rigorous analysis and implementation of preventive measures with detailed, comprehensive surveillance in terms of geography, risk factor detection and different care sectors.

Notes

Competing interests

C. Berdin, S. Schneitler, T. Kaspers, B. Gärtner, A. Halfmann, S. L. Becker, F. Berger and N. Walzer: in general no conflict of interest. Just as a general information, a small portion of the underlying data were previously included in Kaspers et al. [44] as part of the overall project, though under a different evaluative framework and to address separate research questions. Parts of the study were funded by start-up financing from the state of Saarland. S. Schneitler is involved in voluntary work for the German Society for Tropical Medicine, Travel Medicine and Global Health (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Tropenmedizin, Reisemedizin und Globale Gesundheit e.V.) and the Network for Young Infectious Medicine (Netzwerk junge Infektionsmedizin e.V.).

References

[1] World Health Organization (WHO). 10 global health issues to track in 2021. 2020 Dec 24 [accessed 2023 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/10-global-health-issues-to-track-in-2021[2] World Health Organization (WHO). WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. 2017 Feb 27 [accessed 2023 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed

[3] Hamprecht AG, Göttig S. Häufigkeit und Vorkommen multiresistenter gramnegativer Erreger: 3MRGN/4MRGN [Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2018 May;143(9):625-33. DOI: 10.1055/s-0043-113597

[4] Werner G, Abu Sin M, Bahrs C, Brogden S, Feßler AT, Hagel S, Kaspar H, Köck R, Kreienbrock L, Krüger-Haker H, Maechler F, Noll I, Pletz MW, Tenhagen BA, Schwarz S, Walther B, Mielke M. Therapierelevante Antibiotikaresistenzen im One-Health-Kontext [Therapy-relevant antibiotic resistances in a One Health context]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2023 Jun;66(6):628-43. DOI: 10.1007/s00103-023-03713-4

[5] Bundesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit; Paul-Ehrlich-Gesellschaft für Chemotherapie e.V. GERMAP 2015?: Antibiotika-Resistenz und -Verbrauch: Bericht über den Antibiotikaverbrauch und die Verbreitung von Antibiotikaresistenzen in der Human- und Veterinärmedizin in Deutschland. Rheinbach: Antiinfectives Intelligence; 2016.

[6] Tang KL, Caffrey NP, Nóbrega DB, Cork SC, Ronksley PE, Barkema HW, Polachek AJ, Ganshorn H, Sharma N, Kellner JD, Ghali WA. Restricting the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals and its associations with antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals and human beings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2017 Nov;1(8):e316-e327. DOI: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30141-9

[7] Denkel LA, Gastmeier P, Leistner R. The association of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-E) carriage in humans with pigs. Epidemiol Infect. 2016 Mar;144(4):691-2. DOI: 10.1017/S095026881500240X

[8] National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (U.S.) - Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. COVID-19: U.S. Impact on Antimicrobial Resistance, Special Report 2022. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2022. DOI: 10.15620/cdc:117915

[9] Kommission für Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention (KRINKO). Hygienemaßnahmen bei Infektionen oder Besiedlung mit multiresistenten gramnegativen Stäbchen: Empfehlung der Kommission für Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention (KRINKO) beim Robert Koch-Institut (RKI). Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2012;55:1311-54. DOI: 10.1007/s00103-012-1549-5

[10] Robert-Koch-Institut. ESBL und AmpC: ß-Laktamasen als eine Hauptursache der Cephalosporin-Resistenz bei Enterobakterien. Epidemiol Bull. 2007;28:248-50. DOI: 10.25646/4297

[11] Pfeifer Y, Eller C. Aktuelle Daten und Trends zur β-Lactam-Resistenz bei gramnegativen Infektionserregern. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforsch - Gesundheitsschutz. 2012;55:1405-9. DOI: 10.1007/s00103-012-1558-4

[12] Valenza G. Multiresistente gramnegative Stäbchenbakterien auf der Intensivstation: Epidemiologie, Prävention und Therapieoptionen [Multidrug-resistant gram-negative rods in the intensive care unit: Epidemiology, prevention and treatment options]. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2019 Apr;114(3):263-75. DOI: 10.1007/s00063-019-0547-x

[13] Kuenzli E, Jaeger VK, Frei R, Neumayr A, DeCrom S, Haller S, Blum J, Widmer AF, Furrer H, Battegay M, Endimiani A, Hatz C. High colonization rates of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli in Swiss travellers to South Asia - a prospective observational multicentre cohort study looking at epidemiology, microbiology and risk factors. BMC Infect Dis. 2014 Oct 1;14:528. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-528

[14] Lübbert C, Straube L, Stein C, Makarewicz O, Schubert S, Mössner J, Pletz MW, Rodloff AC. Colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in international travelers returning to Germany. Int J Med Microbiol. 2015 Jan;305(1):148-56. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.12.001

[15] Tängdén T, Cars O, Melhus A, Löwdin E. Foreign travel is a major risk factor for colonization with Escherichia coli producing CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a prospective study with Swedish volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010 Sep;54(9):3564-8. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00220-10

[16] Brown LD, Cai TT, Das Gupta A. Interval estimation for a binomial proportion. Stat Sci. 2001;16(2):101-33. DOI: 10.1214/ss/1009213286

[17] Tenenbaum T, Becker KP, Lange B, Martin A, Schäfer P, Weichert S, Schroten H. Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant Organisms in Hospitalized Pediatric Refugees in an University Children's Hospital in Germany 2015-2016. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Nov;37(11):1310-4. DOI: 10.1017/ice.2016.179

[18] Oelmeier de Murcia K, Glatz B, Willems S, Kossow A, Strobel M, Stühmer B, Schaumburg F, Mellmann A, Kipp F, Schmitz R, Möllers M. Prevalence of Multidrug Resistant Bacteria in Refugees: A Prospective Case Control Study in an Obstetric Cohort. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2017 Jun;221(3):132-6. DOI: 10.1055/s-0043-102579

[19] Dahms C, Hübner NO, Kossow A, Mellmann A, Dittmann K, Kramer A. Occurrence of ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli in Livestock and Farm Workers in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany. PLoS One. 2015 Nov 25;10(11):e0143326. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143326

[20] Hogardt M, Proba P, Mischler D, Cuny C, Kempf VA, Heudorf U. Current prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms in long-term care facilities in the Rhine-Main district, Germany, 2013. Euro Surveill. 2015 Jul 2;20(26):21171. DOI: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.26.21171

[21] Steul K, Schmehl C, Berres M, Hofmann S, Klaus-Altschuck A, Hogardt M, Kempf VA, Pohl M, Heudorf U. Multiresistente Erreger (MRE) in der Rehabilitation: Prävalenz und Risikofaktoren für MRGN und VRE [Multidrug Resistant Organisms (MDRO) in Rehabilitation: Prevalence and Risk Factors for MRGN and VRE]. Rehabilitation (Stuttg). 2020 Dec;59(6):366-75. DOI: 10.1055/a-1199-9083

[22] Neumann N, Mischler D, Cuny C, Hogardt M, Kempf VA, Heudorf U. Multiresistente Erreger bei Patienten ambulanter Pflegedienste im Rhein-Main-Gebiet 2014: Prävalenz und Risikofaktoren [Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) in patients in outpatient care in the Rhine-Main region, Germany, in 2014: Prevalence and risk factors]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2016 Feb;59(2):292-300. DOI: 10.1007/s00103-015-2290-7

[23] Heudorf U, Färber D, Mischler D, Schade M, Zinn C, Cuny C, Nillius D, Herrmann M. Multiresistente Erreger in Rehabilitationseinrichtungen im Rhein-Main-Gebiet, Deutschland, 2014: I. Prävalenz und Risikofaktoren [Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDRO) in Rehabilitation Clinics in the Rhine-Main-District, Germany, 2014: Prevalence and Risk Factors]. Rehabilitation (Stuttg). 2015 Oct;54(5):339-45. DOI: 10.1055/s-0035-1559642

[24] Sommer L, Hackel T, Hofmann A, Hoffmann J, Hennebach E, Köpke B, Sydow W, Ehrhard I, Chaberny IF. Multiresistente Bakterien bei Patienten in Krankenhäusern und Arztpraxen sowie bei Bewohnern von Altenpflegeheimen in Sachsen – Ergebnisse einer Prävalenzstudie 2017/2018 [Multi-Resistant Bacteria in Patients in Hospitals and Medical Practices as well as in Residents of Nursing Homes in Saxony – Results of a Prevalence Study 2017/2018]. Gesundheitswesen. 2021 Sep;83(8-09):624-31. DOI: 10.1055/a-1138-0489

[25] Symanzik C, Hillenbrand J, Stasielowicz L, Greie JC, Friedrich AW, Pulz M, John SM, Esser J. Novel insights into pivotal risk factors for rectal carriage of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing enterobacterales within the general population in Lower Saxony, Germany. J Appl Microbiol. 2022 Apr;132(4):3256-64. DOI: 10.1111/jam.15399

[26] Meurs L, Lempp FS, Lippmann N, Trawinski H, Rodloff AC, Eckardt M, Klingeberg A, Eckmanns T, Walter J, Lübbert C; Rai Study group. Intestinal colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacterales (ESBL-PE) during long distance travel: A cohort study in a German travel clinic (2016-2017). Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 Jan-Feb;33:101521. DOI: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2019.101521

[27] Schaumburg F, Sertic SM, Correa-Martinez C, Mellmann A, Köck R, Becker K. Acquisition and colonization dynamics of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria during international travel: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019 Oct;25(10):1287.e1-1287.e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.002

[28] Kommission für Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention (KRINKO). Händehygiene in Einrichtungen des Gesundheitswesens?: Empfehlung der Kommission für Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention (KRINKO) beim Robert Koch-Institut (RKI). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2016;59:1189-220. DOI: 10.1007/s00103-016-2416-6

[29] Rohde AM, Zweigner J, Wiese-Posselt M, Schwab F, Behnke M, Kola A, Schröder W, Peter S, Tacconelli E, Wille T, Feihl S, Querbach C, Gebhardt F, Gölz H, Schneider C, Mischnik A, Vehreschild MJGT, Seifert H, Kern WV, Gastmeier P, Hamprecht A. Prevalence of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales colonization on hospital admission and ESBL genotype-specific risk factors: a cross-sectional study in six German university hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020 Jun 1;75(6):1631-8. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkaa052

[30] Rodríguez-Molina D, Berglund F, Blaak H, Flach CF, Kemper M, Marutescu L, Pircalabioru Gradisteanu G, Popa M, Spießberger B, Wengenroth L, Chifiriuc MC, Larsson DGJ, Nowak D, Radon K, de Roda Husman AM, Wieser A, Schmitt H. International Travel as a Risk Factor for Carriage of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli in a Large Sample of European Individuals-The AWARE Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Apr 14;19(8):4758. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19084758

[31] Robert Koch-Institut. ARS Statistik 2017-2023: Stationäre & ambulante Versorgung. [accessed 2024 Oct 27]. Available from: https://www.gbe-bund.de/gbe/

[32] Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. Demografischer Wandel in Deutschland. Heft 2: Auswirkungen auf Krankenhausbehandlungen und Pflegebedüftige in Bund und Länder. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 2010.

[33] Dormann H, Eichelsdörfer L, Karg MV, Mang H, Schumacher AK. Screening auf 4MRGN in deutschen Notaufnahmen [Screening for 4MRGN in German emergency departments]. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2021 Jun;116(5):440-8. DOI: 10.1007/s00063-020-00678-z

[34] Stoliaroff-Pépin A, Arvand M, Mielke M. Bericht zum Treffen der Moderatoren der regionalen MRE-Netzwerke am Robert Koch-Institut. Epidemiol Bull. 2017;41:465-70.

[35] Lotfinejad N, Peters A, Tartari E, Fankhauser-Rodriguez C, Pires D, Pittet D. Hand hygiene in health care: 20 years of ongoing advances and perspectives. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Aug;21(8):e209-e221. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00383-2

[36] van den Bunt G, Liakopoulos A, Mevius DJ, Geurts Y, Fluit AC, Bonten MJ, Mughini-Gras L, van Pelt W. ESBL/AmpC-producing Enterobacteriaceae in households with children of preschool age: prevalence, risk factors and co-carriage. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017 Feb;72(2):589-95. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkw443

[37] Riccio ME, Verschuuren T, Conzelmann N, Martak D, Meunier A, Salamanca E, Delgado M, Guther J, Peter S, Paganini J, Martischang R, Sauser J, de Kraker MEA, Cherkaoui A, Fluit AC, Cooper BS, Hocquet D, Kluytmans JAJW, Tacconelli E, Rodriguez-Baño J, Harbarth S; MODERN WP2 study group. Household acquisition and transmission of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) -producing Enterobacteriaceae after hospital discharge of ESBL-positive index patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021 Sep;27(9):1322-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.024

[38] Maechler F, Geffers C, Schwab F, Peña Diaz LA, Behnke M, Gastmeier P. Entwicklung der Resistenzsituation in Deutschland: Wo stehen wir wirklich? [Development of antimicrobial resistance in Germany: What is the current situation?]. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2017 Apr;112(3):186-91. DOI: 10.1007/s00063-017-0272-2

[39] European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; World Health Organization. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Europe, 2021 data. Stockholm: 2021.

[40] European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial consumption in the EU/EEA (ESAC-Net) - Annual Epidemiological Report for 2021. Stockholm: 2022.

[41] Seneghini M, Rüfenacht S, Babouee-Flury B, Flury D, Schlegel M, Kuster SP, Kohler PP. It is complicated: Potential short- and long-term impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on antimicrobial resistance-An expert review. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2022 Feb 18;2(1):e27. DOI: 10.1017/ash.2022.10

[42] Szczuka Z, Abraham C, Baban A, Brooks S, Cipolletta S, Danso E, Dombrowski SU, Gan Y, Gaspar T, de Matos MG, Griva K, Jongenelis M, Keller J, Knoll N, Ma J, Miah MAA, Morgan K, Peraud W, Quintard B, Shah V, Schenkel K, Scholz U, Schwarzer R, Siwa M, Szymanski K, Taut D, Tomaino SCM, Vilchinsky N, Wolf H, Luszczynska A. The trajectory of COVID-19 pandemic and handwashing adherence: findings from 14 countries. BMC Public Health. 2021 Oct 5;21(1):1791. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-021-11822-5

[43] Russotto A, Rolfini E, Paladini G, Gastaldo C, Vicentini C, Zotti CM. Hand Hygiene and Antimicrobial Resistance in the COVID-19 Era: An Observational Study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023 Mar 15;12(3):583. DOI: 10.3390/antibiotics12030583

[44] Kaspers T, Berdin C, Staub T, Gärtner B, Berger F, Halfmann A, Becker SL, Schneitler S. A preliminary analysis of hand disinfection use by travellers and their colonisation-risk with multi-resistant bacteria: A proof-of-concept study. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2025 May-Jun;65:102837. DOI: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2025.102837

[45] Kiefer T, Völler H, Nothroff J, Schikora M, von Podewils S, Sicher C, Bartels-Reinisch B, Heyne K, Haase H, Jünger M, Daeschlein G. Multiresistente Erreger in der onkologischen und kardiologischen Rehabilitation – Ergebnisse einer Surveillancestudie in Brandenburg [Multiresistant Pathogens in Oncological and Cardiological Rehabilitation – Results of a Surveillance Study in Brandenburg]. Rehabilitation (Stuttg). 2019 Apr;58(2):136-42. DOI: 10.1055/a-0638-9226

[46] Valenza G, Nickel S, Pfeifer Y, Pietsch M, Voigtländer E, Lehner-Reindl V, Höller C. Prevalence and genetic diversity of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli in nursing homes in Bavaria, Germany. Vet Microbiol. 2017 Feb;200:138-41. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.10.008