Evaluation of the antibacterial effects of four essential oils on antibiotic-resistant bacteria isolated from ventilator-dependent patients

Mohammadamin Shabani 1Mohammadhassan Tajvidi-Monfared 2

Zahra Taheri-Kharameh 3

Faraz Mojab 4

Saeed Shams 5

Hassan Vahidi Emami 6

Iman Khahan-Yazdi 1

1 Student Research Committee, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

2 Student Research Committee, Mazandaran University, Mazandaran, Iran

3 Spiritual Health Research Center, Department of public Health, School of Health, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

4 School of Pharmacy, Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center, Department of Pharmacognosy, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5 Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

6 Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tehran, Iran

Abstract

Background: Antibacterial resistance has become a critical global health concern. In recent years, significant efforts have been made to discover and utilize natural plant-based products as alternative antibacterial agents. This study aims to evaluate the antibacterial effects of essential oils from four medicinal plants against drug-resistant bacteria isolated from tracheal cultures of ventilator-dependent patients.

Materials and methods: Essential oils were extracted from Oliveria decumbens, Zataria multiflora, Cuminum cyminum, and Trachyspermum ammi using a Clevenger apparatus. The antibacterial efficacy was tested against drug-resistant bacterial strains, including four strains of Escherichia (E.) coli, five strains of Klebsiella (K.) pneumoniae, and four strains of Pseudomonas (P.) aeruginosa, all isolated from the sputum of ventilator-dependent patients. The disk diffusion method was used to assess antibacterial activity, and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) method was employed to evaluate the antibacterial properties of the two most effective essential oils.

Results: The antibiogram results demonstrated that Trachyspermum ammi produced the largest inhibition zones against all bacteria, followed by Oliveria decumbens. Trachyspermum ammi showed the highest antibacterial activity against E. coli, while Oliveria decumbens was most effective against K. pneumoniae. In MIC testing, Oliveria decumbens exhibited a stronger antibacterial effect at lower concentrations compared to Trachyspermum ammi.

Conclusion: This study is the first to report the antibacterial effects of the essential oils from all four plants, particularly Trachyspermum ammi and Oliveria decumbens, against bacteria isolated from ventilator-dependent patients. Both plants show promising potential as antibacterial agents against these drug-resistant bacteria.

Keywords

Oliveria decumbens, Zataria multiflora, Cuminum cyminum, Trachyspermum ammi, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, antibiotic resistance

Introduction

Antibacterial resistance has rapidly emerged as a pressing global health issue, placing a significant strain on healthcare systems. The scarcity of effective antibiotics has complicated the treatment of infections, making medical interventions and invasive procedures considerably riskier [1], [2]. According to the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention, over 2.8 million cases of antibiotic-resistant infections occur annually, leading to more than 35,000 deaths. Projections indicate that by 2050, deaths attributed to microbial resistance could rise to 10 million [3], [4], [5].

Antibiotic resistance is an adaptive response to antibacterial agents, stemming from the overuse and misuse of antibiotics. This has resulted in the emergence of new strains that differ from their predecessors, contributing to numerous health challenges [6]. The six primary pathogens associated with antibiotic-resistant fatalities are Escherichia (E.) coli followed by Staphylococcus (S.) aureus, Klebsiella (K.) pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas (P.) aeruginosa [7], [8]. A key health priority is the development of effective antibacterial drugs to combat multidrug-resistant bacteria, particularly among Gram-negative pathogens [9].

In the past decade, significant strides have been made in exploring natural plant products as potential new antibacterial agents [10]. Natural products serve as valuable reservoirs of antibacterial compounds with considerable promise for addressing emerging bacterial strains [11]. Notably, the diversity and accessibility of natural plant compounds, along with their various mechanisms of action and established clinical efficacy, can be attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds (including simple phenols, phenolic acids, quinones, flavonoids, tannins, and coumarins), terpenoids, alkaloids, lectins, and polypeptides, which are fundamental to the antibacterial properties of medicinal plants [12], [13]. The varied climatic conditions in Iran have fostered a rich diversity of vascular-plant flora, making the utilization of this vast resource particularly significant in this context [14].

Oliveria decumbens [Apiaceae] is a herbaceous plant native to Iran, predominantly found in the southern and western regions. In traditional Iranian medicine, it is employed as a liver and heart tonic, as well as for its anti-diarrheal, antipyretic, and digestive properties. Furthermore, its antibacterial, antioxidant, antitumor, and insecticidal activities have been substantiated [15], [16].

Zataria (Z.) multiflora [Lamiaceae] thrives in southern and central Iran and is traditionally used for both culinary and medicinal purposes. The plant exhibits various pharmacological effects, including bronchodilation, vasodilation, and anti-inflammatory properties. The essential oil extracted from Z. multiflora demonstrates strong antibacterial activity against E. coli, S. aureus, and Salmonella typhimurium [16].

Trachyspermum ammi [Apiaceae] is extensively cultivated across Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. The essential oil derived from this plant is utilized in a wide array of medicinal applications, such as antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, cytotoxic, antilithic, nematicidal, anthelmintic, and antifilarial treatments. Its seeds possess notable digestive and antiseptic properties and are primarily employed in traditional medicine to address intestinal disorders such as indigestion, flatulence, and diarrhea [17].

Cuminum cyminum [Apiaceae] is predominantly grown in arid and semi-arid regions, including Iran, China, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, as well as India. Traditionally, this plant is widely used in medicine for treating digestive issues, inflammatory conditions, nervous disorders, and toothache. In traditional Iranian medicine, Cuminum cyminum is utilized to treat conditions such as colic, diarrhea, indigestion, and flatulence, as well as to promote breast milk production. Cuminum cyminum also shows promise in inhibiting biofilm formation and possesses notable antibacterial properties against various bacterial pathogens, particularly gram-negative strains [18].

While numerous studies have explored the effects of these medicinal plants on different bacteria, there has been limited research specifically investigating the antibacterial properties of essential oils derived from medicinal plants against drug-resistant bacteria isolated from clinical samples. Consequently, the aim of this study was to examine the antibacterial effects of essential oils from several species of medicinal plants native to Iran on drug-resistant clinical microorganisms isolated from tracheal culture samples of patients on ventilators with hospital-acquired infections.

Materials and methods

This study was carried out in April and May 2022 at the Cell and Molecular Research Center of Qom University of Medical Sciences, with support from the Qom University of Medical Sciences, under the ethics approval code IR.MUQ.REC.1401.068.

Plant collection

The aerial parts of Oliveria decumbens were collected from Kazeroon city, Fars Province, at an altitude of 860 m. The aerial parts of Zataria multiflora, seeds of Trachyspermum ammi, and aerial parts of Cuminum cyminum were provided by a co-author, a pharmacognosist, from the Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. All plant materials were authenticated by a pharmacognosist for verification.

Essential oil preparation

The collected plant materials were dried in the shade. An accurate weight of 100 g was taken from each sample, which was then ground using an electric mill. Each 100-g portion of plant powder was distilled separately for three hours using a Clevenger apparatus. The extracted essential oils were collected from the Clevenger apparatus and stored in dark vials at 4°C in a refrigerator until required for experimentation.

Sampling

13 clinical strains were obtained from the microbiology department of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran. These included four strains of E. coli, five strains of K. pneumoniae, and four strains of P. aeruginosa. The strains were isolated from tracheal samples of patients in ICU departments across Tehran hospitals who were suffering from nosocomial infections. Notably, these strains exhibited high resistance to antibiotics, including the production of extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) and metallo beta-lactamase (MBL); both P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae showed resistance to all tested antibiotics [19]. Each strain was assigned a unique identification code.

Determining the antimicrobial properties of essential oils using the disk-diffusion method

Initially, bacteria were cultured on Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar (Ibresco, Iran) for 24 hours. A fresh bacterial suspension was then prepared to a concentration of 0.5 McFarland (1.5×108 cfu/ml). Using a sterile swab, the suspension was evenly spread across Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) (Ibresco, Iran) to create a lawn culture. Subsequently, 20 µl of each essential oil was placed on blank disks, and four disks containing each essential oil were positioned on the agar plate at regular intervals. After incubating for 24 hours at 37°C, the diameter of the inhibition zone was measured. The two essential oils that exhibited the most significant antibacterial effect were selected for further testing.

Determining the antibacterial properties of essential oils using the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) method

The MIC of the two essential oils with the largest inhibition zones was assessed. To achieve this, an eight-fold dilution series (50%, 25%, 12.5%, 6.25%, 3.125%, 1.56%, 0.78%, and 0.39% v/v) of the essential oils was prepared in a 96-well microplate (SPL, South Korea) and added to the wells. Bacteria, prepared to half McFarland’s standard, were then introduced into each well. Additionally, one well containing only the culture medium and bacteria (without essential oil) served as a positive control, while another well containing essential oil and culture medium (without bacteria) acted as a negative control. After incubating for 24 hours at 37°C, turbidity was assessed, and the last well showing no turbidity (indicating no bacterial growth) was recorded as the MIC.

Results

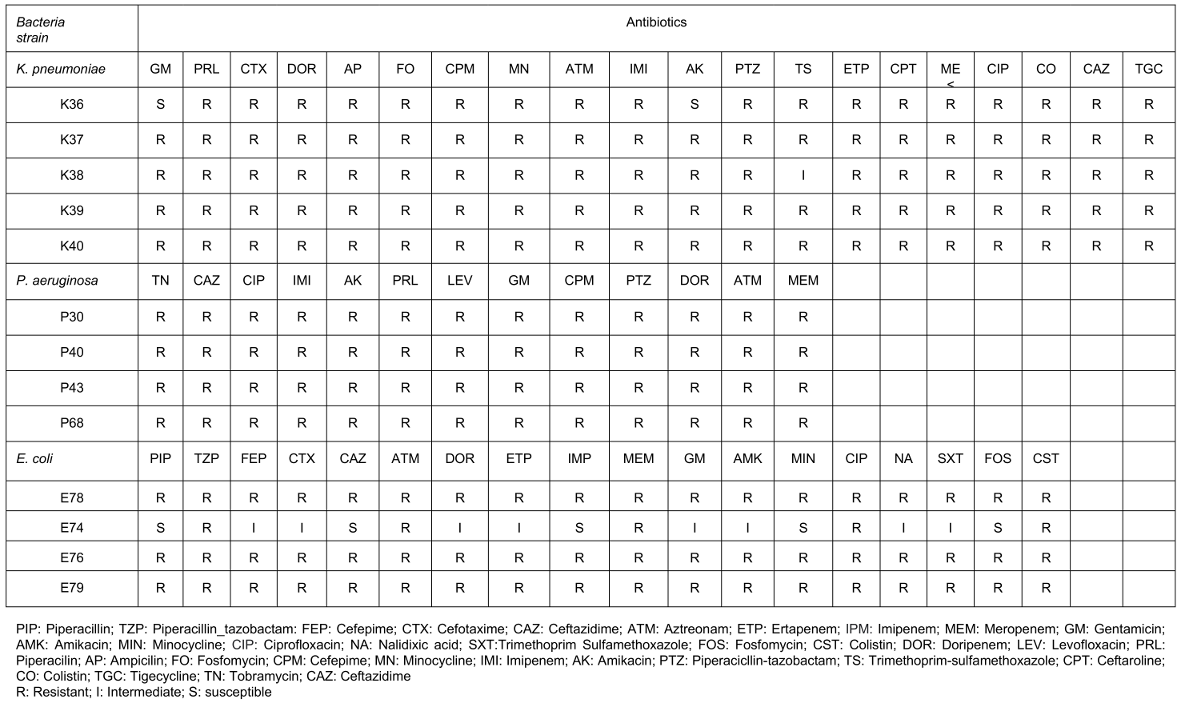

The antibiotic resistance profile of K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli isolates revealed a high level of resistance to multiple antibiotics, emphasizing the need for alternative antibacterial agents. The detailed resistance patterns for each bacterial strain are outlined in Table 1 [Tab. 1].

Table 1: Resistance of bacterial strains of K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa and E. coli against different antibiotics

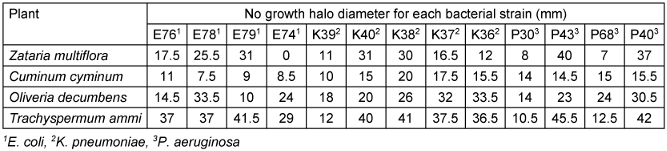

The antibiogram analysis revealed that among the tested essential oils, Trachyspermum ammi exhibited the highest antibacterial activity against all bacterial strains, followed closely by Oliveria decumbens. Specifically, Trachyspermum ammi demonstrated the most potent inhibitory effect against E. coli, whereas Oliveria decumbens was most effective against K. pneumoniae. The detailed inhibition zone diameters for each bacterial strain are presented in Table 2 [Tab. 2].

Table 2: Antibacterial effect of essential oils of Zataria multiflora, Cuminum cyminum, Oliveria decumbens and Trachyspermum ammi by disk diffusion method

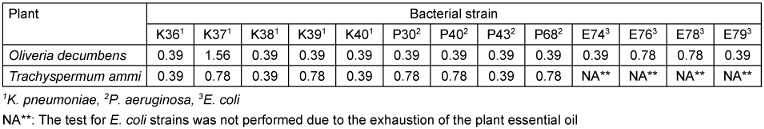

According to the MIC results, although both extracts had inhibitory effects equal to 0.39 v/v, a greater number of strains were inhibited by Oliveria decumbens extract at this concentration, and therefore it showed a better antibacterial effect than Trachyspermum ammi extract. The complete MIC data are presented in Table 3 [Tab. 3].

Table 3: Antibacterial effect of the essential oils of Oliveria decumbens and Trachyspermum ammi by MIC method (v/v)

Discussion

Antibacterial resistance poses a significant threat to global health, leading to substantial challenges within healthcare systems [20], [21], [22]. Among the antibiotic-resistant pathogens are E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa, which are responsible for numerous fatalities, particularly among hospitalized patients [7]. E. coli is one of the most prevalent causes of infections globally. The widespread use of cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones has led to a dramatic increase in multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains. These findings underscore the urgent need for alternative treatments for MDR E. coli infections [23], [24], [25].

P. aeruginosa is an opportunistic bacterial pathogen linked to various infections, including nosocomial infections, endocarditis, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, septicemia, as well as skin, eye, and ear infections [26]. Similarly, K. pneumoniae is a significant Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen associated with a range of infectious diseases, such as urinary tract infections, bacteremia, pneumonia, and liver abscesses. The emergence of MDR strains of K. pneumoniae and their rapid global spread is particularly concerning [27]. In light of widespread antibiotic resistance, researchers are actively seeking more effective compounds as alternatives. Recently, there has been growing interest in using plants for infection treatment [28]. Therefore, this study evaluates three plant types that have been previously researched against clinical strains with high antibiotic resistance.

In our research, the essential oil of the Trachyspermum ammi plant exhibited the strongest antibacterial effect across all tested bacteria, especially against E. coli. Jebelli Javan et al. [29] identified the synergistic effects of Trachyspermum ammi essential oil combined with propolis ethanolic extract on foodborne bacteria. Another study involving Modareskia [30] found that Trachyspermum ammi essential oil demonstrated bacteriostatic activity against S. aureus and E. coli. Additionally, it was shown that the essential oil of Trachyspermum ammi, rich in monoterpenes, possesses considerable antibacterial properties against MDR S. aureus and P. aeruginosa [31].

Following Trachyspermum ammi, Oliveria decumbens exhibited the next highest antibacterial effect in our study. Mahboubi et al. [32] found that Gram-positive bacteria were generally more sensitive than Gram-negative strains using standard microbial strains, with P. aeruginosa displaying notable resistance. However, the advantage of our study is that it focused on antibiotic-resistant clinical strains. Eftekhari et al. [33] also explored the antibacterial properties of Oliveria decumbens essential oil using the disk diffusion method on both Gram-negative (E. coli, P. aeruginosa) and Gram-positive bacteria (S. epidermidis, S. aureus). Their findings indicated strong antibacterial activity against S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and E. coli, but no effect against P. aeruginosa at concentrations up to 20.4 µg/mL. In our study, the essential oil of Zataria multiflora demonstrated moderate antibacterial activity. Research conducted by Golkar et al. [34] evaluated the antibacterial effects of Zataria multiflora on E. coli (ATCC35218), reporting a non-growth halo diameter of 6.4 mm and a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 5 µg/mL. In contrast, our findings indicated an average non-growth halo diameter of 19 mm for E. coli. A review by Khaledi et al. [35] generally confirmed the antibacterial properties of thyme against P. aeruginosa under laboratory conditions. Interestingly, our previous study highlighted the superior efficacy of Zataria multiflora against clinical strains of P. aeruginosa [36].

Additionally, another study assessed the antibacterial properties of essential oils from Artemisia kermanensis, Lavandula officinalis, and Zataria multiflora against S. aureus (ATCC 25923), P. aeruginosa (PTCC 1310), and K. pneumoniae (PTCC 1053). The results indicated that all three essential oils exhibited inhibitory effects, with Zataria multiflora demonstrating the most significant antibacterial activity against the tested strains [37].

In the present investigation, Cuminum cyminum essential oil exhibited the weakest antibacterial properties. On average, it had the least impact on E. coli compared to other bacteria. A study by Oroojalian et al. [38] explored the effects of Carum copticum, Bunium persicum, and Cuminum cyminum on various bacteria, including S. aureus, B. cereus, Listeria monocytogenes, E. coli O157:H7, and Salmonella enteritidis. They found that while the MIC values for the essential oils of Bunium persicum and Cuminum cyminum were less effective than that of Carum copticum, their combined use showed promising results, particularly against Gram-positive bacteria.

Limitations

The study had several limitations that may affect the interpretation and generalizability of its findings. Firstly, the essential oils were extracted using only the Clevenger apparatus, potentially overlooking variations in antibacterial properties that might arise from different extraction methods. Furthermore, the in-vitro nature of the study does not account for the complexities of human infections, such as biofilm formation and host immune responses. Additionally, while the study identified Trachyspermum ammi and Oliveria decumbens as effective antibacterial agents, it did not explore the specific mechanisms of action or assess potential cytotoxicity, which are crucial for evaluating their safety and therapeutic potential in clinical settings. Lastly, one of the limitations of the study was the completion of the Trachyspermum ammi essential oil and the failure to calculate the MIC value for the E. coli. Limited availability of sufficient plant material for extraction resulted in incomplete testing of Trachyspermum ammi essential oil, preventing a comprehensive evaluation of its antibacterial efficacy.

Conclusion

This study highlights the promising potential of essential oils from medicinal plants as effective antibacterial agents against antibiotic-resistant bacteria isolated from ventilator-dependent patients. Given the growing global concern surrounding antibacterial resistance, our findings underscore the importance of exploring natural alternatives to conventional antibiotics.

The essential oils extracted from Trachyspermum ammi and Oliveria decumbens demonstrated significant antibacterial activity, with Trachyspermum ammi exhibiting the largest zones of inhibition across all tested strains, particularly against E. coli. Conversely, Oliveria decumbens showed remarkable efficacy against K. pneumoniae, especially at lower concentrations during the MIC assessments. These results suggest that the essential oils from these plants may serve as valuable adjuncts in the treatment of infections caused by drug-resistant pathogens, potentially offering new avenues for therapeutic strategies in clinical settings.

Notes

Authors’ ORCIDs

- Khahan-Yazdi I: 0000-0002-6034-955X

- Mohammadamin Shabani: 0000-0002-2333-8122

- Tajvidi-Monfared M: 0000-0003-3179-2189

- Taheri Kharameh Z: 0000-0002-9968-7951

- Mojab F: 0000-0003-2415-2175

- Shams S: 0000-0002-3701-3126

- Vahidi Emami H: 0000-0002-5355-6921

Funding

This study was funded by Qom University of Medical Sciences and Health Services.

Acknowledgments

This research represents the culmination of a project carried out at Qom University of Medical Sciences, under the Code of IR.MUQ.REC.1401.068. The project received support from both Qom University of Medical Sciences and the National Elite Foundation. Consequently, the researchers would like to extend their heartfelt gratitude and appreciation to all individuals who contributed to this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Sannathimmappa MB, Nambiar V, Aravindakshan R. Antibiotics at the crossroads - Do we have any therapeutic alternatives to control the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance? J Educ Health Promot. 2021 Nov 30;10:438. DOI: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_557_21[2] Tosi M, Roat E, De Biasi S, Munari E, Venturelli S, Coloretti I, Biagioni E, Cossarizza A, Girardis M. Multidrug resistant bacteria in critically ill patients: a step further antibiotic therapy. J Emerg Crit Care Med. 2018;2:103. DOI: 10.21037/jeccm.2018.11.08

[3] Chen K, Wu W, Hou X, Yang Q, Li Z. A review: antimicrobial properties of several medicinal plants widely used in traditional chinese medicine. Food Qual Saf. 2021 Sep 04;5:fyab020. DOI: 10.1093/fqsafe/fyab020

[4] Huang L, Ahmed S, Gu Y, Huang J, An B, Wu C, Zhou Y, Cheng G. The effects of natural products and environmental conditions on antimicrobial resistance. Molecules. 2021 Jul 14;26(14):4277. DOI: 10.3390/molecules26144277

[5] Miró-Canturri A, Ayerbe-Algaba R, Smani Y. Drug repurposing for the treatment of bacterial and fungal infections. Front Microbiol. 2019 Jan 28;10:41. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00041

[6] Chandra H, Bishnoi P, Yadav A, Patni B, Mishra AP, Nautiyal AR. Antimicrobial resistance and he alternative resources with special emphasis on plant-based antimicrobials—a review. Plants. 2017 Apr 10;6(2):16. DOI: 10.3390/plants6020016

[7] Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022 Feb 12;399(10325):629-55. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0

[8] Sharifipour E, Shams S, Esmkhani M, Khodadadi J, Fotouhi-Ardakani R, Koohpaei A, Doosti Z, Ej Golzari S. Evaluation of bacterial co-infections of the respiratory tract in COVID-19 patients admitted to ICU. BMC Infect Dis. 2020 Sep;20(1):646. DOI: 10.1186/s12879-020-05374-z

[9] Butler MS, Paterson DL. Antibiotics in the clinical pipeline in October 2019. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2020 Jun;73(6):329-64. DOI: 10.1038/s41429-020-0291-8

[10] He Q. Antibacterial activity of traditional herbal medicine. Access Microbiol. 2019 Apr 08;1(1A):1. DOI: 10.1099/acmi.ac2019.po0266

[11] Yan Y, Li X, Zhang C, Lv L, Gao B, Li M. Research progress on antibacterial activities and mechanisms of natural alkaloids: A review. Antibiotics. 2021 Mar 19;10(3):318. DOI: 10.3390/antibiotics10030318

[12] Porras G, Chassagne F, Lyles JT, Marquez L, Dettweiler M, Salam AM, Samarakoon T, Shabih S, Farrokhi DR, Quave CL. Ethnobotany and the Role of Plant Natural Products in Antibiotic Drug Discovery. Chem Rev. 2021 Mar 24;121(6):3495-560. DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00922

[13] Hartady T, Syamsunarno MRAA, Priosoeryanto BP, Jasni S, Balia RL. Review of herbal medicine works in the avian species. Vet World. 2021 Nov;14(11):2889-906. DOI: 10.14202/vetworld.2021.2889-2906

[14] Baradaran M, Jalali A. A Review on Antibacterial Effects of Iranian Herbal Medicine on Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Jundishapur J Chron Dis Care. 2019 Oct 23;8(4). DOI: 10.5812/jjcdc.96058

[15] Karami A, Khoushbakht T, Esmaeili H, Maggi F. Essential Oil Chemical Variability in Oliveria decumbens (Apiaceae) from Different Regions of Iran and Its Relationship with Environmental Factors. Plants (Basel). 2020 May 27;9(6):680. DOI: 10.3390/plants9060680

[16] Khazdair MR, Ghorani V, Alavinezhad A, Boskabady MH. Pharmacological effects of Zataria multiflora Boiss L. and its constituents focus on their anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2018 Feb;32(1):26-50. DOI: 10.1111/fcp.12331

[17] Anwar S, Ahmed N, Habibatni S, Abusamra Y. Ajwain (Trachyspermum ammi L.) Oils. In: Preedy VR, editor. Essential Oils in Food Preservation, flavor and safety. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2016. p. 181-92.

[18] Allaq AA, Sidik NJ, Abdul-Aziz A, Ahmed IA. Cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.): A review of its ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry. Biomed Res Ther. 2020 Sep 30;7(9):4016-21. DOI: 10.15419/bmrat.v7i9.634

[19] Gaur P, Hada V, Rath RS, Mohanty A, Singh P, Rukadikar A. Interpretation of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Using European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Breakpoints: Analysis of Agreement. Cureus. 2023 Mar 31;15(3):e36977. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.36977

[20] Derakhshan Sefidi M, Heidary L, Shams S. Prevalence of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ISOLATES in Iran: A meta-analysis. Infect Epidemiol Microbiol. 2021 Nov 20;7(1):77-99. DOI: 10.52547/iem.7.1.77

[21] Moradia S, Fouladi-Farda R, Aalia R, Dolatib M, Shamsb S, Asadi-Ghalharia M, et al. Identification of β-lactam-resistant coding genes in the treatment plant by activated sludge process. Desalination Water Treat. 2023 Jan;281:137-49. DOI: 10.5004/dwt.2023.29127

[22] Ghorbanalizadgan M, Bakhshi B, Shams S, Najar-Peerayeh S. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis fingerprinting of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli strains isolated from clinical specimens, Iran. Int Microbiol. 2019 Sep;22(3):391-8. DOI: 10.1007/s10123-019-00062-8

[23] Shams S, Hashemi A, Esmkhani M, Kermani S, Shams E, Piccirillo A. Imipenem resistance in clinical Escherichia coli from Qom, Iran. BMC Res Notes. 2018 May;11(1):314. DOI: 10.1186/s13104-018-3406-6

[24] Holland MS, Nobrega D, Peirano G, Naugler C, Church DL, Pitout JDD. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli causing bloodstream infections in a centralized Canadian region: a population-based surveillance study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Nov;26(11):1554.e1-1554.e8. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.02.019

[25] Sojo-Dorado J, López-Hernández I, Rosso-Fernandez C, Morales IM, Palacios-Baena ZR, Hernández-Torres A, Merino de Lucas E, Escolà-Vergé L, Bereciartua E, García-Vázquez E, Pintado V, Boix-Palop L, Natera-Kindelán C, Sorlí L, Borrell N, Giner-Oncina L, Amador-Prous C, Shaw E, Jover-Saenz A, Molina J, Martínez-Alvarez RM, Dueñas CJ, Calvo-Montes J, Silva JT, Cárdenes MA, Lecuona M, Pomar V, Valiente de Santis L, Yagüe-Guirao G, Lobo-Acosta MA, Merino-Bohórquez V, Pascual A, Rodríguez-Baño J; REIPI-GEIRAS-FOREST group. Effectiveness of Fosfomycin for the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Bacteremic Urinary Tract Infections: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Jan 4;5(1):e2137277. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37277

[26] Shariati A, Azimi T, Ardebili A, Chirani AS, Bahramian A, Pormohammad A, Sadredinamin M, Erfanimanesh S, Bostanghadiri N, Shams S, Hashemi A. Insertional inactivation of oprD in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients in Tehran, Iran. New Microbes New Infect. 2017 Dec 1;21:75-80. DOI: 10.1016/j.nmni.2017.10.013

[27] Wang G, Zhao G, Chao X, Xie L, Wang H. The Characteristic of Virulence, Biofilm and Antibiotic Resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Aug 28;17(17):6278. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph17176278

[28] Khahan-Yazdi I, Shabani M, Tajvidi-Monfared M, Emami HV, Mojab F, Shams S, et al. Effectiveness of medicinal plant essential oils on drug-resistant bacteria in Iran: A systematic review. J Med Plants. 2023 Dec 31;22(87):26-38. DOI: 10.61186/jmp.22.87.26

[29] Jebelli Javan A, Salimiraad S, Khorshidpour B. Combined effect of Trachyspermum ammi essential oil and propolis ethanolic extract on some foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Vet Res Forum. 2019 Summer;10(3):235-40. DOI: 10.30466/vrf.2019.72986.1991

[30] Modareskia M, Fattahi M, Mirjalili MH. Thymol screening, phenolic contents, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Iranian populations of Trachyspermum ammi (L.) Sprague (Apiaceae). Sci Rep. 2022 Sep 19;12(1):15645. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-19594-7

[31] Hosseinkhani F, Jabalameli F, Banar M, Abdellahi N, Taherikalani M, Leeuwen WB, Emaneini M. Monoterpene isolated from the essential oil of Trachyspermum ammi is cytotoxic to multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus strains. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2016 Apr;49(2):172-6. DOI: 10.1590/0037-8682-0329-2015

[32] Mahboubi M, Feizabadi M, Haghi G, Hosseini H. Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of essential oil from Oliveria decumbens Vent. Iran J Med Aroma Plants Res. 2008 Sep 17.

[33] Eftekhari M, Shams Ardekani MR, Amin M, Attar F, Akbarzadeh T, Safavi M, Karimpour-Razkenari E, Amini M, Isman M, Khanavi M. Oliveria decumbens, a Bioactive Essential Oil: Chemical Composition and Biological Activities. Iran J Pharm Res. 2019 Winter;18(1):412-21.

[34] Golkar P, Mosavat N, Jalali SAH. Essential oils, chemical constituents, antioxidant, antibacterial and in vitro cytotoxic activity of different Thymus species and Zataria multiflora collected from Iran. S Afr J Bot. 2020 Jan 22;130:250-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.sajb.2019.12.005

[35] Khaledi A, Meskini M. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Satureja Khuzestanica Jamzad and Zataria Multiflora Boiss against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Iran J Med Sci. 2020 Mar;45(2):83-90. DOI: 10.30476/IJMS.2019.72570

[36] Hashemi A, Shams S, Barati M, Samedani A. Antibacterial effects of methanolic extracts of Zataria multiflora, Myrtus communis and Peganum harmala on Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing ESBL. J Arak Univ Med Sci. 2011;14(4):104-12.

[37] Gavanji S, Mohammadi E, Larki B, Bakhtari A. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic evaluation of some herbal essential oils in comparison with common antibiotics in bioassay condition. Integr Med Res. 2014 Sep;3(3):142-152. DOI: 10.1016/j.imr.2014.07.001

[38] Oroojalian F, Kasra-Kermanshahi R, Azizi M, Bassami M. Synergistic antibacterial activity of the essential oils from three medicinal plants against some important food-borne pathogens by microdilution method. Iran J Med Aroma Plant Res. 2010;26(2):133-46. DOI: 10.22092/ijmapr.2010.6836