[Blutkultur-Entnahme in der zentralen Notaufnahme der Klinik für Innere Medizin des Krankenhauses Nordwest Frankfurt am Main]

Maximilian Theo Skowronek 11 Medizinische Klinik 1: Klinik für Pneumologie, Beatmungs- und Intensivmedizin, Gastroenterologie, Kardiologie und Nephrologie, Krankenhaus Nordwest, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Zusammenfassung

Die zentrale Notaufnahme ist für PatientInnen häufig die erste Instanz zur Einleitung einer mikrobiologischen Diagnostik und Antiinfektivatherapie. Blutkulturen (BK) stellen aktuell (2025) den Goldstandard der Erregerdiagnostik im menschlichen Blut dar. In dieser retrospektiven Untersuchung sollte durch Personalschulungen und Etablierung einer Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) zur Entnahme von BK-Paaren die Anzahl adäquat entnommener BK-Paare (≥2 BK-Paare), eine Reduktion der Kontaminationsrate und eine Reduktion falsch-positiver BK-Paare bei internistischen PatientInnen, welche eine Antiinfektivatherapie in der zentralen Notaufnahme erhalten haben, erreicht werden. Die retrospektive Auswertung erfolgte jeweils über drei Monate (Juli–September) 2024 und 2025. Im Juni 2025 erfolgten die Etablierung der SOP und die Personalschulungen. Insgesamt wurden 325 PatientInnen im Vergleichszeitraum (2024) und 289 PatientInnen im Interventionszeitraum (2025) eingeschlossen. Es konnte gezeigt werden, dass es im Interventionszeitraum (2025) zu einer signifikanten Zunahme (p=0,001) der adäquat entnommenen BK-Paare (≥2 BK-Paare) um 45,86% kam. Weiterhin zeigte sich im Interventionszeitraum (2025) gegenüber dem Vergleichszeitraum (2024) eine signifikante Abnahme (p=0,001) der unzureichend-entnommenen BK-Paare (<2) um 8,81%. Die Kontaminationsrate konnte nicht-signifikant (p<0,05) mit p=0,010 von 13,37% (2024) auf 7,52% (2025) gesenkt werden. Ebenfalls konnte der Anteil der falsch-positiven BK-Paare von allen positiven BK-Paaren nicht-signifikant (p=0,106) um 12,06% im Interventionszeitraum gesenkt werden. Diese Interventionsstudie konnte zeigen, dass Personalschulungen und eine SOP zu Blutkulturen eine signifikante Verbesserung der mikrobiologischen Präanalytik in Form von Qualität und Quantität bewirken können. Dies könnte zu einer Verbesserung der Patientenversorgung beitragen, indem nicht indizierte Antiinfektivatherapien vermieden und eine adäquate Erregerdiagnostik ermöglicht werden.

1 Introduction

Blood cultures (BC) are currently the gold standard for diagnosing pathogenic microorganisms in the blood. They form the basis for detecting bloodstream infections [1]. The aim of blood cultures is to enable rapid and precise identification of the pathogen in order to initiate targeted anti-infective therapy. This approach can significantly reduce mortality, length of hospital stay, and associated treatment costs [2]. The following clinical situations or suspected diagnoses are indications for blood culture collection: sepsis, septic shock, fever of unknown origin (FUO), fever in neutropenia/aplasia, endocarditis, cyclic generalized infection (e.g., typhoid fever, brucellosis), severe localized infections, before any anti-infective administration in cases of systemic inflammation and catheter-, implant-, and artificial heart valve-associated infections [1], [3]. In addition, candidemia/fungemia and Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia are indications for taking blood cultures every 48 to 72 hours [4], [5]. In general, blood cultures should be taken when infection is suspected, regardless of fever or chills [1], [3], [6], [7]. Taking blood cultures during anti-infective therapy may also be useful in the absence of clinical convalescence and pathogen detection. However, this should be done immediately before the next administration of anti-infective agents in order to increase the probability of detection at the lowest anti-infective concentration [8], [9].

In general, a blood culture pair consists of an aerobic and an anaerobic bottle, each filled with a culture medium [3], [10]. At least two blood culture pairs (aerobic/anaerobic) should always be taken [1], [3], [7], [11], [12]. The detection rate can be significantly increased by taking a larger number of blood culture pairs [13]. According to current hygiene recommendations, it is no longer necessary to take samples from two different puncture sites [11]. When taking samples, care must be taken to ensure adequate hygiene in order to avoid any contamination. Depending on the study, the general contamination rate (proportion of contaminated blood cultures out of all microbiologically processed blood cultures) ranges between 5.7% [14] and 8.2% [15]. In the context of quality assurance, it is defined as a quality indicator [9]. Internationally, a contamination rate of less than 3% is targeted for blood cultures taken from peripheral veins [1]. Furthermore, the proportion of false-positive blood cultures among all positive blood cultures is relevant [1]. The proportion of false-positive blood cultures varies between 13.3% [14] and 47.8% [15].

Common microorganisms that are more likely to be considered contamination include: coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), Micrococcus spp., Propionibacterium acnes, Corynebacterium spp., Bacillus spp. (not B. anthracis), α-hemolytic (green) streptococci [1]. However, the patient context, clinical situation, and medical history must always be taken into account, which is why the detection of these microorganisms should not automatically be considered contamination [1].

2 Methodology

The objectives of the intervention study at Northwest Hospital were to optimize blood culture collection (standardization of at least two blood culture pairs prior to anti-infective therapy), reduce microbiological contamination findings (contamination rate <3%), and improve pathogen diagnostics (reduction of false-positive blood culture pairs). Data collection was carried out retrospectively after approval by Northwest Hospital (July 8, 2025) in two periods: from July 1, 2024, to September 30, 2024, (three months) and from July 1, 2025, to September 30, 2025 (three months).

Patients had to meet the following three inclusion criteria:

- Presentation at the internal medicine emergency department of Frankfurt am Main Northwest Hospital

- Initiation of anti-infective therapy in the emergency department

- Subsequent inpatient admission

For data collection, patients were retrospectively reviewed using the ORBIS hospital information system (HIS) based on the criteria. The data was evaluated and processed using Microsoft Excel 2024, Microsoft Word 2019, and Jamovi (statistics program).

Prior to the intervention period from July to September 2025, an intervention took place in the form of the creation and establishment of an SOP for paired blood culture collection (structural indicator) and several training sessions for nursing and medical staff (process indicator) on paired blood culture collection in the central emergency room (see SOP in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]).

3 Results

In order to statistically record the influence of the intervention (training + SOP), the Chi²/χ² test was performed in addition to descriptive statistics. Cramér’s V was calculated to record the effect size. The significance level was set at α=0.05.

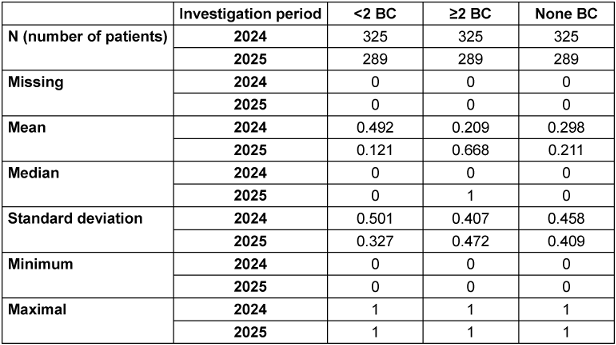

Between July and September 2024, a total of 1,261 patients were examined in detail, of whom 325 were included in the study. In 160 (49.23%) patients, fewer than two pairs of blood cultures were taken. In 68 (20.92%) patients, two or more pairs of blood cultures were taken before anti-infective therapy. No blood culture pairs were taken from 97 (29.84%) patients prior to anti-infective therapy. Thus, 257 (79.07%) patients did not receive the recommended pathogen diagnostics prior to anti-infective therapy. From July to September 2025, a total of 1,402 patients were examined in detail, of whom 289 were included. In 35 (12.11%) patients, fewer than two pairs of blood cultures were taken. In 61 (21.1%) patients, no pairs of blood cultures were taken before anti-infective therapy. In 193 (66.78%) patients, two or more pairs of blood cultures were taken before anti-infective therapy (see Table 1 [Tab. 1]).

Table 1: Total number of patients, mean, median, and standard deviation for cases with <2 BC, ≥2 BC, and no BC in the respective study periods 2024 and 2025

The analysis showed that there was a significant increase (p=0.001) of 45.86% in adequately collected blood culture pairs (≥2 BC pairs) in the intervention period (2025) compared to the comparison period (2024). The effect size (Cramér’s V) for the comparison was 0.463, indicating a strong effect of the intervention. Furthermore, during the intervention period (2025) compared to the reference period (2024), there was a significant decrease (p=0.001) in inadequately collected blood culture pairs (<2) of 8.81%. The effect size (Cramér’s V) for the comparison was 0.398, indicating a moderate to strong effect of the intervention. In addition, a significant decrease (p=0.013) of 8.74% in completely missing blood culture pairs was demonstrated in the intervention period (2025) compared to the comparison period (2024) (see Table 1 [Tab. 1]).

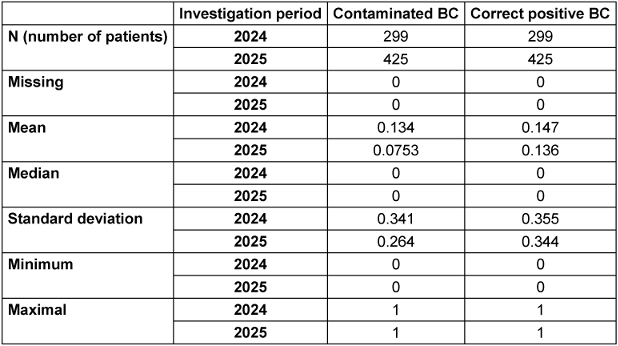

In the comparison period (2024), a total of 299 blood culture pairs were collected. Of these, 40 blood culture pairs were assessed as contaminated. This corresponds to a contamination rate of 13.37%. The proportion of false-positive blood culture pairs out of all positive blood culture pairs (84) was 47.61%. During the intervention period (2025), a total of 425 blood culture pairs were collected. Of these, 32 were assessed as contaminated. This results in a contamination rate of 7.52% (see Table 2 [Tab. 2]).

Table 2: Total number of BC, mean, median, and standard deviation of contaminated and correct positive BC in the respective study periods 2024 and 2025

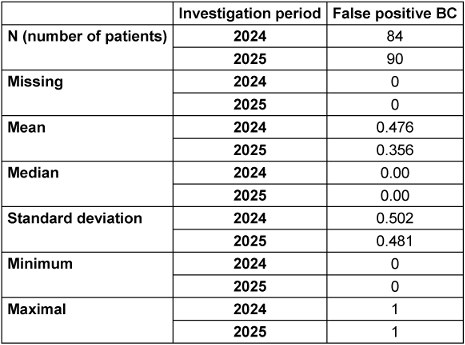

The proportion of false-positive blood culture pairs out of all positive blood culture pairs (90) was 35.55%. The reduction in the contamination rate from 13.37% (2024) to 7.52% in the intervention period reached the significance level (α=0.05) with p=0.010. The 12.06% reduction in false-positive blood culture pairs out of all positive blood culture pairs was not significant (p=0.106) (see Table 3 [Tab. 3]).

Table 3: Total number of positive BC. Mean, median, standard deviation of false-positive BC in the respective period

4 Discussion

Blood cultures remain the gold standard for diagnosing pathogenic microorganisms in the blood [1] and are indispensable (as of 2025) for the fastest possible identification of pathogenic organisms in the blood and for adequate and targeted anti-infective therapy.

This study showed that in the first study period (July to September 2024), 79% of patients did not have adequate blood cultures taken (<2 BC pairs or no BC taken) before starting anti-infective therapy in the emergency room. This significantly reduces pathogen identification with possible relevant consequences for the further care of patients [16]. In our study, training of nursing and medical staff and the establishment of an SOP for blood culture pair collection resulted in a significant increase (p=0.001) of 45.86% in adequately collected blood culture pairs (≥2 BC pairs). The effect size (Cramér’s V) was rated as strong at 0.463. Furthermore, compared to the reference period, a significant (p=0.001) decrease of 8.81% in inadequately collected blood culture pairs (<2) was achieved during the intervention period. The effect size (Cramér’s V) was rated as moderate at 0.398. The intervention also significantly (p=0.013) reduced the complete absence of blood culture pairs (0 blood culture pairs collected) before the initiation of anti-infective therapy by 8.74%. We were thus able to demonstrate that our interventions resulted in a significant improvement in blood culture pair collection. This supports the results of a study by Dutta et al., which showed that training emergency room staff led to an increase in blood culture pair collection with an increased positivity rate of blood cultures [17].

The contamination rate was also significantly reduced (p=0.010) by 5.85% to 7.52%, and the false-positive blood culture pairs were reduced non-significantly (p=0.106) by 12.06% to 35.55%. This could be due to the establishment of the SOP, which explicitly emphasizes compliance with hygiene measures and the use of blood culture adapters when collecting blood cultures. International studies have already shown that various blood culture adapters can significantly reduce the contamination rate [18], [19]. Internationally, a contamination rate of <3% of blood cultures is the target [1], but unfortunately, our intervention was unable to achieve this.

The high turnover of nursing and medical staff in the emergency room poses a significant challenge to ensuring consistent, high-quality standards of care. The regular turnover of nursing and medical staff in the internal medicine department of the central emergency room at Northwest Hospital may also have contributed to the observed differences in results due to varying levels of knowledge regarding anti-infective therapy, the handling of blood cultures, and varying medical experience. Regardless of the results, only the total number of blood cultures taken, the number of positive blood cultures, and the contamination rate could be used for quality assurance. Direct verification or control of the implementation of the SOP (e.g., compliance with hygiene measures, use of blood culture adapters, sufficient filling quantity per blood culture bottle, etc.) was not possible due to the personnel required for this. Further ongoing training and recommendations for action are therefore necessary to achieve further improvement.

In summary, it has been shown that establishing SOPs and providing ongoing education for medical and nursing staff can optimize blood culture collection (≥2 BC pairs) prior to anti-infective therapy and reduce the contamination rate and false-positive blood cultures. This could contribute to improving patient care in the future by avoiding unnecessary anti-infective therapies and enabling adequate pathogen diagnostics. This could reduce antibiotic-associated harm [20] and additional costs due to prolonged hospital stays [21]. In addition, the implementation of blood culture adapters (see SOP in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]) could reduce the risk of self-injury among staff, although there are currently no evidence-based studies available on this. Further scientific research is therefore needed to continuously improve the infectious disease and microbiological aspects of preanalytics.

5 Conclusion

In summary, it has been shown that establishing SOPs and providing ongoing education for medical and nursing staff can optimize blood culture collection (≥2 BC pairs) prior to anti-infective therapy and reduce the contamination rate and false-positive blood cultures. This could contribute to improving patient care in the future by avoiding unnecessary anti-infective therapy and enabling adequate pathogen diagnosis. This could reduce antibiotic-associated harm [20] and additional costs due to prolonged hospital stays [21]. In addition, the implementation of blood culture adapters (see SOP in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]) could reduce the risk of self-injury among staff, although there are currently no evidence-based studies available on this. Further scientific research is therefore needed to continuously improve the infectious disease and microbiological aspects of preanalytics.

Abbreviations

- BC: blood culture/blood culture pair

- FUO: fever of unknown origin

- HIS: hospital information system

- SOP: standard operating procedure

Notes

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

References

[1] Prävention von Infektionen, die von Gefäßkathetern ausgehen: Hinweise zur Blutkulturdiagnostik. Informativer Anhang 1 zur Empfehlung der Kommission für Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention (KRINKO) beim Robert Koch-Institut. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2017 Feb;60(2):216-30. DOI: 10.1007/s00103-016-2485-6[2] Allerberger F, Kern WV. Bacterial bloodstream infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Feb;26(2):140-1. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.10.004

[3] Schulz-Stübner S, editor. Repetitorium Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention. 3rd ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2022. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-662-65994-6

[4] Cortés JA, Valderrama-Rios MC, Peçanha-Pietrobom PM, Júnior MS, Diaz-Brochero C, Robles-Torres RR, Espinosa-Almanza CJ, Nocua-Báez LC, Nucci M, Álvarez-Moreno CA, Queiroz-Telles F, Rabagliati R, Rojas-Fermín R, Finquelievich JL, Riera F, Cornejo-Juárez P, Corzo-León DE, Cuéllar LE, Zurita J, Hernández AR, Colombo AL. Evidence-based clinical standard for the diagnosis and treatment of candidemia in critically ill patients in the intensive care unit. Braz J Infect Dis. 2025;29(1):104495. DOI: 10.1016/j.bjid.2024.104495

[5] Kimmig A, Hagel S, Weis S, Bahrs C, Löffler B, Pletz MW. Management of Bloodstream Infections. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:616524. DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2020.616524

[6] Fabre V, Sharara SL, Salinas AB, Carroll KC, Desai S, Cosgrove SE. Does This Patient Need Blood Cultures? A Scoping Review of Indications for Blood Cultures in Adult Nonneutropenic Inpatients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Aug;71(5):1339-47. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciaa039

[7] Garcia RA, Spitzer ED, Beaudry J, Beck C, Diblasi R, Gilleeny-Blabac M, Haugaard C, Heuschneider S, Kranz BP, McLean K, Morales KL, Owens S, Paciella ME, Torregrosa E. Multidisciplinary team review of best practices for collection and handling of blood cultures to determine effective interventions for increasing the yield of true-positive bacteremias, reducing contamination, and eliminating false-positive central line-associated bloodstream infections. Am J Infect Control. 2015 Nov;43(11):1222-37. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.030

[8] Ziegler R. SOP Entnahme von Blutkulturen mittels peripherer Venenpunktion. Intensivmedizin up2date. 2023;19(04):375-9. DOI: 10.1055/a-2193-4277

[9] Ziegler R. SOP Entnahme von Blutkulturen mittels peripherer Venenpunktion. Intensivmedizin up2date. 2022;17(01):11-5. DOI: 10.1055/a-1263-3019

[10] Jung N, Rieg S, Lehmann C, editors. Klinikleitfaden Infektiologie 2024. 2nd ed. Munich: Urban & Fischer; 2024.

[11] Deutsche Sepsis-Gesellschaft e. V., et al. S3-Leitlinie: Sepsis – Prävention, Diagnose, Therapie und Nachsorge – Update 2025. Langfassung, Version 4.0, AWMF-Registernummer: 079-001. Berlin: AWMF; 2025 [accessed 2025 Sep 25]. Available from: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/079-001

[12] Reimer LG, Wilson ML, Weinstein MP. Update on detection of bacteremia and fungemia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997 Jul;10(3):444-65. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.10.3.444

[13] Lee A, Mirrett S, Reller LB, Weinstein MP. Detection of bloodstream infections in adults: how many blood cultures are needed? J Clin Microbiol. 2007 Nov;45(11):3546-8. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.01555-07

[14] Washer LL, Chenoweth C, Kim HW, Rogers MA, Malani AN, Riddell J 4th, Kuhn L, Noeyack B Jr, Neusius H, Newton DW, Saint S, Flanders SA. Blood culture contamination: a randomized trial evaluating the comparative effectiveness of 3 skin antiseptic interventions. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013 Jan;34(1):15-21. DOI: 10.1086/668777

[15] Harvey DJ, Albert S. Standardized definition of contamination and evidence-based target necessary for high-quality blood culture contamination rate audit. J Hosp Infect. 2013 Mar;83(3):265-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.11.004

[16] Scheer CS, Fuchs C, Gründling M, Vollmer M, Bast J, Bohnert JA, Zimmermann K, Hahnenkamp K, Rehberg S, Kuhn SO. Impact of antibiotic administration on blood culture positivity at the beginning of sepsis: a prospective clinical cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019 Mar;25(3):326-31. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.05.016

[17] Dutta S, McEvoy DS, Rubins DM, Dighe AS, Filbin MR, Rhee C. Clinical decision support improves blood culture collection before intravenous antibiotic administration in the emergency department. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022 Sep;29(10):1705-14. DOI: 10.1093/jamia/ocac115

[18] Wiener-Well Y, Levin PD, Assous MV, Algur N, Barchad OW, Lachish T, Zalut T, Yinnon AM, Ben-Chetrit E. The use of a diversion tube to reduce blood culture contamination: A "real-life" quality improvement intervention study. Am J Infect Control. 2023 Sep;51(9):999-1003. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2023.02.015

[19] Callado GY, Lin V, Thottacherry E, Marins TA, Martino MDV, Salinas JL, Marra AR. Diagnostic Stewardship: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Blood Collection Diversion Devices Used to Reduce Blood Culture Contamination and Improve the Accuracy of Diagnosis in Clinical Settings. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023 Sep;10(9):ofad433. DOI: 10.1093/ofid/ofad433

[20] Bauer KA, Kullar R, Gilchrist M, File TM Jr. Antibiotics and adverse events: the role of antimicrobial stewardship programs in 'doing no harm'. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2019 Dec;32(6):553-8. DOI: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000604

[21] Bassetti M, Rello J, Blasi F, Goossens H, Sotgiu G, Tavoschi L, Zasowski EJ, Arber MR, McCool R, Patterson JV, Longshaw CM, Lopes S, Manissero D, Nguyen ST, Tone K, Aliberti S. Systematic review of the impact of appropriate versus inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy on outcomes of patients with severe bacterial infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Dec;56(6):106184. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106184

Attachments

| Attachment 1 | SOP: Taking blood cultures from inpatients – Internal Medicine – Central Emergency Room – Northwest Hospital (lab000051_Attachment1.pdf, application/pdf, 98.69 KBytes) |