[Reiseassoziierte Malaria im Rhein-Main-Gebiet: Eine Auswertung der im Zentralinstitut für Labormedizin, Mikrobiologie und Krankenhaushygiene am Krankenhaus Nordwest in Frankfurt/Main, Deutschland, diagnostizierten Fälle von 2003 bis 2022]

Vanessa Kienberger 1Oliver Müller 2

Klaus-Peter Hunfeld 1

1 Institute for Laboratory Medicine, Microbiology & Infection Control, Northwest Medical Centre, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

2 University of Applied Sciences Kaiserslautern, Molecular Oncology, Zweibrücken, Germany

Zusammenfassung

Im Rhein-Main-Gebiet, einer dynamischen Region mit zahlreichen Reisenden und Neuankömmlingen aus verschiedenen Ländern, ist die reiseassoziierte Malaria von großer Relevanz. Allerdings gibt es in Deutschland nur wenige Veröffentlichungen bezüglich importierter Malaria auf regionaler Ebene. Ziel dieser Forschung war es, neue Erkenntnisse über epidemiologische und klinische Merkmale der reiseassoziierten Malaria in Frankfurt am Main und im Rhein-Main-Gebiet zu gewinnen. Zu diesem Zweck wurden die zwischen 2003 und 2022 am Zentralinstitut für Labormedizin, Mikrobiologie und Krankenhaushygiene (Krankenhaus Nordwest, Frankfurt am Main) diagnostizierten Malariafälle ausgewertet. Die Ergebnisse wurden anschließend mit den nationalen Surveillance-Daten des Robert Koch Instituts verglichen. Insgesamt wurden im Institut für Labormedizin 44 Malariafälle diagnostiziert. Die Hälfte davon wurde in den letzten sechs Jahren des Untersuchungszeitraums diagnostiziert. Die meisten Patienten (63,6%) waren zwischen 20 und 49 Jahre alt. Das Geschlechterverhältnis war nahezu ausgeglichen (52,3% männlich, 47,7% weiblich). Der häufigste Erreger war Plasmodium falciparum (84,1%). Die meisten Infektionen wurden in Afrika erworben. Eine Besonderheit waren die beiden Fälle von flughafenassoziierter Malaria. Von den 23 Patienten mit Angaben zum Herkunftsland waren 21 ausländischer Herkunft. Neun der zehn Personen, über die Informationen zur Chemoprophylaxe vorlagen, nahmen die Chemoprophylaxe nicht oder nur unregelmäßig ein. 54,5% der Personen, die Angaben zu den Reisegründen machten, besuchten Freunde und Verwandte. Es gab 17 komplizierte Malariafälle, die alle durch Plasmodium falciparum verursacht wurden. Bei Menschen über 45 Jahren war die Wahrscheinlichkeit, schwer zu erkranken, signifikant höher. Bezüglich der Medikation gab es einen zunehmenden Trend bei der Verwendung von Artemether/Lumefantrin. Die Ergebnisse zeigten viele Übereinstimmungen mit den deutschen Surveillance-Daten, aber es gab auch Abweichungen, wie die Geschlechterverteilung und die Entwicklung der Fallzahlen während der COVID-19-Pandemie. Diese Studie liefert wichtige Erkenntnisse über reiseassoziierte Malaria im Rhein-Main-Gebiet. Verstärkte Forschung auf regionaler Ebene kann regionale Unterschiede aufdecken, Verbesserungsmöglichkeiten in der Patientenversorgung aufzeigen und das Bewusstsein für Malaria bei medizinischem Personal und Reisenden stärken.

Schlüsselwörter

reiseassoziierte Malaria, Plasmodium, Epidemiologie, importierte Infektionen, Reisegesundheit, Rhein-Main-Gebiet

1 Introduction

Malaria is one of the most life-threatening vector-borne diseases for humans [1]. For the year 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 249 million cases of malaria in 85 malaria-endemic countries, including 608,000 cases of death [2]. The disease mainly occurs in the tropical regions of sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Oceania and Latin America [3]. In the WHO European Region, most of the cases are imported by international travellers and immigrants, especially to France, Germany, United Kingdom and Italy [4]. Regarding Germany, 768 cases were reported in 2022 [5].

Due to globalisation and the associated increase in travel, malaria continues to be a major concern even in non-endemic countries. Travellers from non-endemic areas such as Germany usually have no or only low levels of acquired immunity, making them particularly susceptible to infection and severe disease [6]. In particular Plasmodium (P.) falciparum, the pathogen that causes malaria tropica, is responsible for a high number of life-threatening disease courses [7]. Even travellers who originate from malaria-endemic areas are at risk when visiting their former homeland, due to the loss of their acquired immunity [6], [8]. At the same time, there are reports of a declining trend in the use of chemoprophylaxis [9]. Therefore, malaria is a highly relevant issue for travel medicine in Germany.

The Robert Koch Institute (RKI) regularly publishes surveillance data on the annually reported malaria cases in Germany [7]. However, little information is published about malaria cases at the regional level, for example in cities or metropolitan areas. There are also only a few studies on travel-associated malaria in German hospitals or laboratories [10], [11], especially for the region of Frankfurt am Main and the Rhine-Main area.

The Rhine-Main area is a vibrant region with numerous travellers and newcomers. In Frankfurt am Main, the number of residents rose to an all-time high at the end of 2022, which was mainly due to an increase in residents of foreign origin. In the same year, over 240,000 people of foreign origin had their main place of residence in Frankfurt am Main. The percentage of the foreign population was thus 31.3% [12]. In addition, thousands of travellers enter the region every year due to the location of Frankfurt Airport. According to the official website of Fraport, the airport handled over 48.9 million passengers in 2022 [13]. In a region like Frankfurt am Main and the Rhine-Main area, with its high volume of travel, cases of imported malaria are of particular interest.

This study examined the cases of travel-associated malaria that were diagnosed between 2003 and 2022 at the Institute for Laboratory Medicine, Microbiology and Infection Control (Northwest Medical Centre) in Frankfurt am Main. It comprises a detailed analysis of the case data regarding various characteristics such as age, gender, pathogen species, country of infection, laboratory results, and treatment. The findings were then compared with the notification data of the Robert Koch Institute.

The aim of the study was to provide important insights into the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of imported Malaria in Frankfurt am Main and the Rhine-Main area.

2 Methods

2.1 Study population

All patients diagnosed positive for malaria at the Institute for Laboratory Medicine, Microbiology and Infection Control at the Northwest Medical Centre in Frankfurt/Main between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2022 were included in the study. In total, the study included 44 cases.

2.2 Collection of data

An overview of all suspected cases since 2003 was obtained via the electronic laboratory system H&S. All patients for whom malaria diagnostics were performed at the Laboratory Institute were classified as suspected cases (occupational health screenings were excluded). Then, all of the positive malaria cases were identified. For each positive case, medical reports with the required data were obtained using the hospital information system ORBIS (Dedalus Healthcare Group, Milan/Italy). When tests were commissioned by external cooperation partners, the medical reports were requested from the respective hospitals.

Among the positive cases, there were two cases of airport-associated malaria. Regarding these cases, Wieters et al. published an article with information about disease progression and treatment (“Two cases of airport-associated falciparum malaria in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, October 2019”, [14]). The data provided in this article were also used in our study (see Figure 1 [Fig. 1]).

Figure 1: Design of data evaluation

The information from the medical reports was entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (in an anonymized form). The following data were collected and analysed:

- Date of diagnosis

- Age

- Gender

- Plasmodium species

- Co-infections

- Region of infection

- Country of origin, country of residence, nationality

- Chemoprophylaxis

- Reasons for travel

- Laboratory reports

- Disease progression (non-severe malaria, severe malaria, death)

- Medication

2.3 Data analysis

The evaluation was performed using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond/Washington) and the statistical software SPSS Statistics (version 29.0.2.0) from IBM (Armonk/New York). While the data were analysed as a whole, they were also examined for changes during the observation period. Since in some years only a few cases were diagnosed, the study period was divided into four-year-intervals for better illustration.

All tables that were created using the study data have been added to Attachment 1 [Att. 1].

2.3.1 Comparison with the data of the Robert Koch Institute

The collected data were compared with the notification data of the Robert Koch Institute. Data on the reported cases in Germany can be accessed via SurvStat@RKI, the database of the RKI for notifiable diseases and pathogens [15]. Further relevant information was accessed via the “Epidemiological Yearbooks of Notifiable Infectious Diseases” that are published annually by the RKI [7], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]. Since the Institute for Laboratory Medicine is located in the state of Hesse, the case numbers were also compared with those gathered by Hesse. The case numbers of the individual federal states are also available on SurvStat@RKI.

The tables that were created using the RKI data have also been added to Attachment 1 [Att. 1].

2.3.2 Medication

The medications that the patients were being treated with were identified, and their relative frequencies were calculated. The treatment methods were examined as a whole and separately for each type of malaria (malaria tertiana, non-severe malaria tropica, severe malaria tropica). In addition, it was examined whether there were changes in treatment over the course of time.

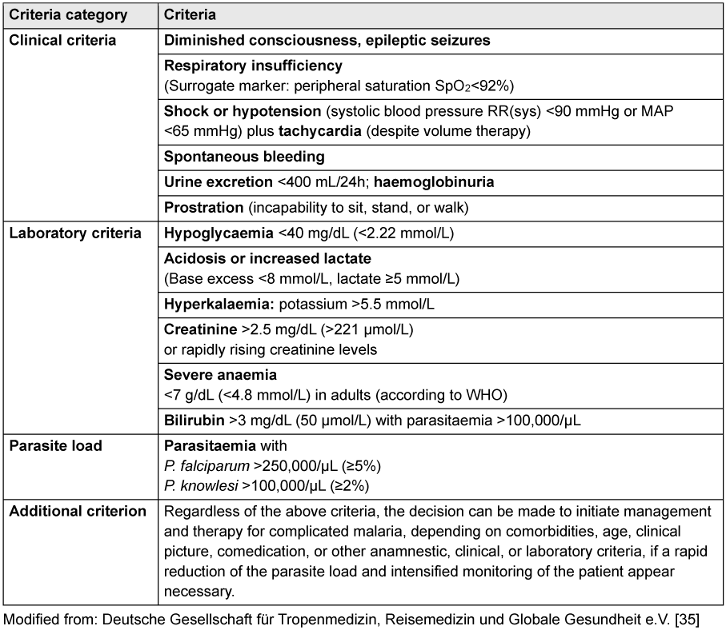

The German Society for Tropical Medicine, Travel Medicine and Global Health (“Deutsche Gesellschaft für Tropenmedizin, Reisemedizin und Globale Gesundheit e.V.” – DTG) has published a guideline that defines the criteria for severe malaria and provides treatment recommendations [35]. This guideline is regularly updated. When analysing the medication, the DTG guideline was used for comparison, for example to see whether trends in medication were also reflected in changes in the guideline.

The study only included treatment that was carried out in Germany. If patients had previously received malaria treatment abroad, only the treatment that was carried out in Germany was taken into account.

2.3.3 Reasons for travel

When indicated in the report, a patient’s reason for travel was determined and divided into the categories “vacation/tourism”, “visiting friends and relatives (VFR)”, “refugee”, and “other reasons”.

2.3.4 Regions of infection

The countries as well as the continents of infection were identified and their percentages calculated. If no country but only a continent or subcontinent was mentioned as the region of infection, the (sub-) continent was assigned as the country of infection (for example, “Africa – no specification”). This was also done when several countries in a region were considered to be possible sources of infection.

2.3.5 Laboratory results

The medical reports contained detailed information about abnormalities in certain laboratory parameters. It was determined how many cases had information about a certain parameter obtainable and how many cases had an abnormality with respect to this parameter (for example, “increased LDH” or “anaemia”). The relative proportion (among those with information on this parameter) was determined (see Table 1 [Tab. 1]). The following laboratory parameters were examined: C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), thrombocytes, leucocytes, haemoglobin (Hb), bilirubin, creatinine, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), sodium, and potassium. The laboratory results were assessed using the internal reference ranges of the Laboratory Institute (the reference limits for the parameters were provided in the table).

Table 1: Table layout for the evaluation of laboratory parameters

For some parameters, statistical tests were performed if a connection with severe malaria was suspected (Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test).

2.3.6 Course of the disease and severe malaria

The proportion of patients with severe malaria was determined. Severe malaria is present when at least one of the criteria for severe malaria as defined by the DTG is fulfilled (see Table 2 [Tab. 2]) [35].

Table 2: Criteria of severe malaria (according to the guideline of the DTG)

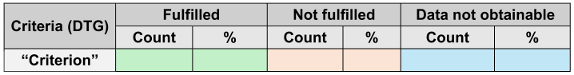

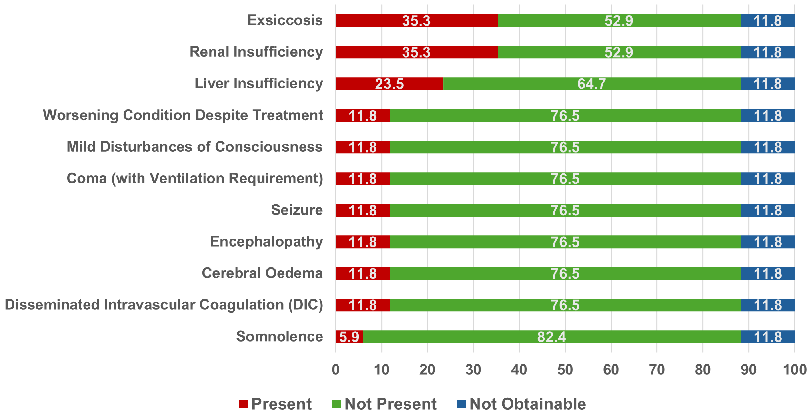

It was checked for each case whether these criteria were met. If at least one criterion was met, the case was categorised as severe malaria. It was also analysed how frequently the respective criteria were met in these patients. This was achieved by creating a table that showed what proportion of the people with severe malaria fulfilled a certain criterion (see Table 3 [Tab. 3]). Since there was not always information available for every single criterion, it was also shown what proportion of the patients with severe malaria did not have data on a particular criterion.

Table 3: Table layout for the evaluation of severe malaria cases

For the evaluation of some criteria, it was occasionally necessary to convert the parasitaemia into parasites/µL, since for most cases, the parasite density was determined as the proportion of infected erythrocytes (in percent or permille). The conversion was performed using the patient’s respective erythrocyte concentration:

Apart from the DTG-criteria, the medical reports usually provided additional information on complications and other clinical manifestations, such as the severity of impaired consciousness or whether there was brain swelling. For this reason, a table was created with other frequently mentioned clinical manifestations and their percentage of the complicated cases (see Table 4 [Tab. 4]). The table included the following complications/manifestations: renal insufficiency, exsiccosis, liver insufficiency, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), cerebral oedema, encephalopathy, seizure, coma, mild disturbances of consciousness (like confusion, dizziness), somnolence, and worsening condition despite treatment.

Table 4: Table layout for the complications of the severe malaria cases

With regard to impairment of consciousness, the patients were only assigned to the most severe form. For example, if a patient was initially somnolent but later in a coma, the patient was only assigned to the “coma” category.

Furthermore, the demographics of the patients with severe malaria were analysed and it was checked whether co-infections occurred. To examine whether there were associations between certain characteristics and the occurrence of complicated disease, crosstabs were created and statistical tests (Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test) were performed. The following characteristics were examined for associations with complicated malaria: age, gender and the presence of co-infections.

2.3.7 Statistical tests

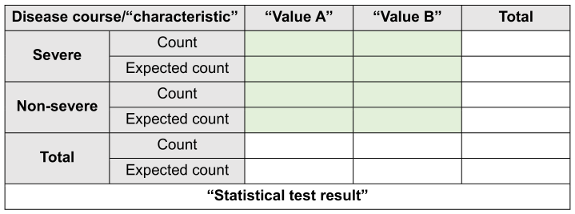

To assess whether there was an association between a characteristic or laboratory parameter and severe malaria, a crosstab was created (see Table 5 [Tab. 5]). Then, either Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was applied.

Table 5: Crosstab design to examine associations with severe malaria

In order to carry out the chi-squared test, certain conditions must be fulfilled [36]:

- The value of the cells “expected count” should be ≥5 in at least 80% of the cells and no cell should have an expected value <1.

- This assumption is most likely to be met if the sample size is at least the number of cells multiplied by five [36] (for example, for a 2x2 table: 4 cells x 5=20; the sample size has to be at least 20).

Every crosstab was checked to see whether it met these conditions. Due to the sample size, the conditions were not met for some characteristics. In these cases, Fisher’s exact test was used, which is also applicable to small sample sizes [37]. When the conditions were fulfilled, Pearson’s chi-squared test was used. The significance level of the tests was 5%.

3 Results

3.1 Case numbers

From 2003 to 2022, 486 suspected cases of malaria were tested at the Institute for Laboratory Medicine at the Northwest Medical Centre in Frankfurt, of which 44 cases were positive. The number of annual positive cases during this period ranged between 0 and six cases per year (see Table S1 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). The only year with six positive cases was 2021. The average number of positive cases per year was 2.2.

According to the Robert Koch Institute, there was a significant increase in the annual malaria cases in 2014/2015 (see Table S2 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). However, the Institute for Laboratory Medicine reported no sharp increase in the number of cases during this period (four cases in 2014 and 0 cases in 2015). In 2020/2021 the RKI reported a decline in the number of malaria infections. This was not the case at the Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre. While the number of suspected cases decreased in these years, there was no sharp decline in the number of positive cases. In fact, 2021 was the year with the most diagnosed cases of malaria.

No clear trend could be determined until 2017. From 2003 to 2017, the annual number of cases fluctuated between 0 and four positive cases. However, an increase could be observed from 2018 onwards. Here, the number of cases fluctuated between two and six malaria cases per year. While the average annual number of cases for the years 2003–2017 was 1.6, it was 4.0 for the period of 2018–2022. Half of the malaria cases were diagnosed during the last six years of the study period (2017–2022; 22 cases). The increase in annual cases also became evident when the investigation period was divided into four-year-intervals (see Figure 2 [Fig. 2]).

Figure 2: Positive malaria cases over the course of time

3.2 Comparison of the data with the cases of Hesse

According to the RKI, there were 1297 cases in the federal state of Hesse from 2003 to 2022 (range 20–130 cases/year). The Laboratory Institute of the Norwest Medical Centre accounted for 3.4% of these cases. The annual percentage of cases in Hesse was on average 4.2% and ranged from 0.0% to 15.8% (see Table S3 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). In 2020 and 2021, the number of reported cases in Hesse was particularly low, but there was no sharp decline in the number of cases at the Laboratory Institute. The cases diagnosed in the Laboratory Institute accounted for a particularly high proportion of the cases in Hesse during these years, 15.0% in 2020 and 15.8% in 2021 (in the previous years: 0.0–7.7%).

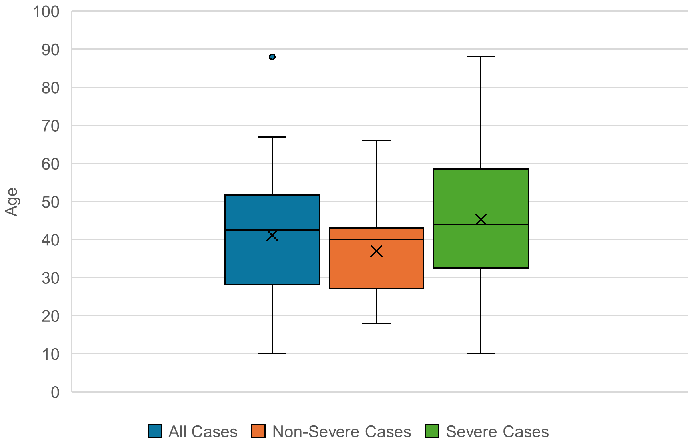

3.3 Age distribution

The age of the patients ranged from ten to 88 years, with an average age of 41.1 years. The median was 42.5 years, with a standard deviation (SD) of 16.3 (see Figure 3 [Fig. 3]).

Figure 3: Age distribution of the patients with malaria

63.6% of the people diagnosed with malaria at the Northwest Medical Centre were between 20 and 49 years old.

When the study patients were divided into age groups (five-year-intervals), the following groups had the largest proportions: The groups of the 40- to 44-year-olds (ten cases; 22.7%), 20- to 24-year-olds (six cases; 13.6%) and 50- to 54-year-olds (five cases; 11.4%) (see Table S4 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]).

According to the RKI, the age groups falling between 20 and 49 years had the largest proportion of reported cases: 65.0% of the cases reported between 2003 and 2022 (with information regarding age) fell within this age range (see Table S6 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]), which was similar to the findings of this study (63.6%).

Regarding age, no obvious trend could be observed over the course of time (see Table S5 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]).

3.4 Gender distribution

The gender distribution among the patients diagnosed with malaria at the Institute for Laboratory Medicine of the Northwest Medical Centre was approximately equal. 23 patients (52.3%) were male, and 21 patients (47.7%) were female.

According to the RKI, in each year of the study period, men accounted for a significantly higher proportion of reported malaria cases than women; of the cases with information on gender, the percentage of men ranged between 66.8% and 77.2%, and the percentage of women between 22.8% and 33.2%. For the entire investigation period, men accounted for 70.6% of the reported cases, and women for 29.4% (see Table S7 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). Consequently, the proportion of women in this study was significantly higher than the proportion of women in the national surveillance data (and the proportion of men was significantly lower than the proportion of men in the national surveillance data).

When looking at the gender distribution over the course of time, no obvious trend could be observed (see Figure 4 [Fig. 4]).

Figure 4: Gender distribution over the course of time

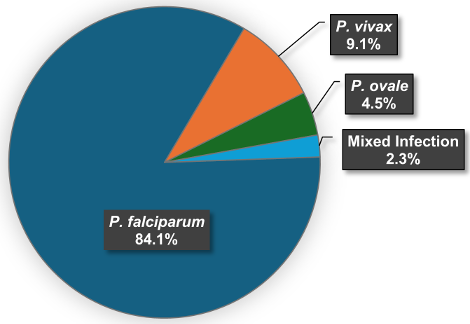

3.5 Plasmodium species

P. falciparum was by far the most frequently diagnosed species (37 cases; 84.1%), followed by P. vivax (four cases; 9.1%) and P. ovale (two cases; 4.5%). There was one mixed infection (2.3%; P. falciparum and an undifferentiated Plasmodium species) (see Figure 5 [Fig. 5]).

Figure 5: Distribution of the malaria cases by Plasmodium spp.

According to RKI data, there were 13,826 reported malaria cases with information on the Plasmodium species in the period of 2003–2022. Of these, P. falciparum had the highest proportion (76.6%), followed by P. vivax (11.9%) and P. ovale (3.4%). P. malariae and mixed infections both accounted for 3.0%. 2.0% were cases of unspecified malaria tertiana. There were sporadic cases of P. knowlesi (ten cases, 0.1%). In every year of the study period, P. falciparum made up the highest percentage of cases (range 55.4%-88.4%, mean 77.3%) (see Table S8 and Table S9 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). The percentage of P. falciparum in this study (84.1%) was slightly higher than the overall percentage of P. falciparum in the national reporting data (76.6%). Nevertheless, P. falciparum was by far the most common species in both data sets.

Regarding P. vivax, P. ovale and mixed infections, the shares of the respective species corresponded to the RKI data. No cases of P. knowlesi and P. malariae were diagnosed at the Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre.

In 2014 and 2015, the Robert Koch Institute reported an increase in the number of P. vivax cases. In 2014, there were 292 cases of P. vivax, accounting for 30.3% of the malaria cases, and in 2015, the number rose to 305 cases, representing 29.7% of the malaria cases of that year (see Table S8 and Table S9 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). However, there was no increase in P. vivax cases at the Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre during this period (2014: one case; 2015: no cases).

When the studied period was divided into four-year-intervals, P. falciparum was the most frequently diagnosed pathogen for every interval (see Figure 6 [Fig. 6]). As a result of the general increase in diagnosed malaria cases, an increasing trend could also be observed for P. falciparum. For P. vivax, P. ovale and mixed infections, there were too few cases to detect a trend.

Figure 6: Absolute frequencies of P. falciparum and other spp. over the course of time

3.6 Co-infections

Of the 44 people diagnosed with malaria at the Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre, information regarding co-infections was available for 39 patients (88.6%). Of these cases, 12 people (30.8%) were reported to have co-infections. The most common co-infections were COVID-19 and pneumonia, each reported twice. All other reported co-infections occurred only once (see Table S10 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). There were no reports of multiple co-infections.

3.7 Regions of infection

Information on the region of infection was available in a total of 40 cases. Of these cases, 35 (87.5%) acquired malaria in Africa (see Table S11 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). For three cases (7.5%), Asia was reported as region of infection. Two cases (5.0%) involved airport malaria, which was acquired at Frankfurt Airport in Germany.

For the malaria infections acquired in Asia, the countries of infection were China, Pakistan and Southeast Asia (the exact country of infection could not be determined).

In total, 18 different countries of infection were identified. The five most common countries of infection were all African countries: Cameroon (nine cases; 22.5%), Ghana (five cases; 12.5%), Nigeria (five cases; 12.5%), Togo (three cases; 7.5%) and Africa without further specification (three cases; 7.5%) (see Table S12 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]).

There were 32 infections from Africa for which the precise region of infection was known. Of these, 18 infections (56.3%) were acquired in West Africa, 12 infections (37.5%) in Central Africa and two infections (6.3%) in East Africa.

The fact that most diagnosed malaria infections were from Africa also matches the data from the Robert Koch Institute: according to the epidemiological yearbooks of the RKI from 2003 to 2022, most malaria infections each year originated from Africa (see Table S13 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]) [7], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]. In this period, Cameroon, Ghana and Nigeria were consistently in the top 5 of the most frequently reported countries for malaria infections, and Togo was consistently in the top 10. The epidemiological yearbooks show that the percentages for Cameroon ranged from 7% to 22%, for Ghana from 8% to 21%, for Nigeria from 11% to 21% and for Togo from 2% to 11% (see Tables S14–S17 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]) [7], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34].

When the infection areas were analysed separately by Plasmodium species, it was noticeable that three of the four cases of P. vivax were acquired in Asia. Therefore, all infections originating from Asia were caused by P. vivax. The fourth case caused by P. vivax was reported to be acquired in Africa (unspecified country). The two infections caused by P. ovale and the mixed infection also originated from Africa. Regarding P. falciparum, all infections were acquired in Africa, except for the two cases of airport malaria, which were acquired in Frankfurt am Main (Germany).

3.8 Residence, nationality, country of origin

Of the 44 malaria cases, the place of residence could be identified for 39 people. Of these, five people (12.8%) lived abroad, while 34 people (87.2%) were resident in Germany.

Nationality could be determined for 35 people. Of these, 24 people (68.6%) had German nationality, and 11 people (31.4%) had a foreign nationality.

Additionally, the country of origin could be determined in 23 cases. Of these, two patients (8.7%) were of German origin, while 21 patients (91.3%) were of foreign origin.

3.9 Use of chemoprophylaxis

Of the 44 cases, ten patients had medical reports that included information on prophylactic behaviour. Eight people stated that they had not taken any chemoprophylaxis. One person reported having taken chemoprophylaxis, but not consistently. One person reported that they had taken chemoprophylaxis, but there was no information about the type and the dosing regimen of the medication taken.

3.10 Reasons for travel

In total, the reasons for travel were ascertainable in 11 cases. Six people stated that they were visiting friends and relatives (54.5%), one person was traveling for vacation/tourism, and two others were refugees. Two of the patients did not fit into any of these categories (“other reasons”) (see Table S18 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]).

3.11 Laboratory results

Considering the absolute frequencies, thrombocytopenia (41 mentions) was reported as the most common abnormality, followed by elevated CRP (38 mentions), anaemia (38 mentions), hyperbilirubinaemia (25 mentions), and elevated LDH levels (25 mentions) (see Table S19 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]).

When looking at the relative proportions, all patients for whom data on CRP or PCT values were available had elevated CRP and PCT. Almost all cases with information about Hb levels had anaemia (92.7%). In addition, almost all people with known platelet levels had thrombocytopenia (97.6%). In people with known leukocyte values, 51.4% had leukocytopenia and 22.9% had leukocytosis. It should be noted that in 5.9% of cases the leukocytes were both increased and decreased over time.

In the cases where information on electrolytes could be collected, just over half (51.4%) had low potassium (<3.40 mmol/L) and about a third (35.3%) had elevated potassium (>4.50 mmol/L). There is also some overlap here: 17.6% had both high and low potassium levels over time. 55.9% had low sodium levels (<136 mmol/L), while 14.7% had elevated sodium levels (>145 mmol/L). In 8.8% of cases, sodium levels were both high and low over time.

Of the people whose bilirubin levels were known, 78.1% had hyperbilirubinaemia. About half of the people with information on creatinine had elevated creatinine levels (48.6%). In 69.4% of patients with known LDH levels, LDH was elevated.

It was noticed that many patients with complicated malaria had elevated creatinine levels (women: >0.90 mg/dL; men: >1.20 mg/dL) and LDH levels (>250 U/L). Therefore, both parameters were tested for a significant association with severe disease.

When creating a crosstab with the parameter creatinine and the disease course and performing Pearson’s chi-squared test, the p-value was 0.003 (see Table S20 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). There was therefore a significant connection between elevated creatinine and the disease course.

When creating a crosstab with the parameter LDH and the disease course and performing Fisher’s exact test, the p-value was 0.005 (see Table S21 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). The test therefore showed that there was a significant association between elevated LDH and the course of the disease.

3.12 Disease course

Of the 44 malaria cases diagnosed at the Institute for Laboratory Medicine at the Northwest Medical Centre, 17 cases (38.6%) met at least one criterion for severe malaria. Non-severe malaria was identified in 23 (52.3%) cases, and 4 cases (9.1%) had insufficient data to determine the severity of disease.

According to the available data, there were no deaths. All of the patients with complete information on disease severity and progression were discharged with significant improvement in their condition.

3.13 Severe malaria

All 17 severe cases were caused by P. falciparum. The two cases of airport malaria were also among the cases with severe disease.

In 11 of the 17 cases, complete information was available regarding criteria for severe malaria. In six cases, the information was incomplete (for example, only information on the criterion of hyperparasitaemia was available). In these cases, it was not possible to check whether other criteria were also met.

Of all criteria, “hyperparasitaemia” was the most frequently met (ten mentions; 58.8%), followed by “diminished consciousness, epileptic seizures” and “bilirubin >3 mg/dL with parasitaemia >100,000/µL” (six mentions each / 35.3%). “Acidosis or increased lactate” and “severe anaemia” each had four mentions or 23.5%. The criteria “shock or hypotension” and “prostration” were both mentioned three times (17.6% each). “Respiratory insufficiency” (two mentions; 11.8%), “urine excretion <400 mL/24h; haemoglobinuria” (one mention; 5.9%), “hyperkalaemia” (one mention; 5.9%) and “creatinine >2.5 mg/dL” (one mention; 5.9%) rarely occurred. “Spontaneous bleeding” and “hypoglycaemia” were not mentioned at all (see Table S22 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1] and Figure 7 [Fig. 7]).

Figure 7: Fulfilment of the DTG-criteria in the severe malaria cases – percentages

The medical reports provide additional information regarding complications and other clinical manifestations observed in the severe cases.

Renal insufficiency (six mentions; 35.3%), exsiccosis (six mentions; 35.3%) and liver insufficiency (four mentions; 23.5%) occurred several times. In addition, cerebral oedema, DIC, encephalopathy and seizure were reported (twice each). One patient was somnolent, two patients had mild disturbances of consciousness such as confusion or dizziness. Two people were in a coma and required ventilation. In two cases, the patients’ health deteriorated despite treatment (they were both transferred to another hospital) (see Table S23 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1] and Figure 8 [Fig. 8]).

Figure 8: Further complications in the severe malaria cases – percentages

Of those with complicated disease, nine were male and eight were female. The gender ratio was therefore approximately equal. To test whether there was a relationship between gender and disease course, a Pearson’s chi-squared test was performed. When creating a crosstab with gender and disease course and performing a Pearson’s chi-squared test, the p-value was 0.962 (the null hypothesis was therefore retained) (see Table S24 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). The test showed that there was no connection between gender and disease course.

The age range for the people with severe malaria was 10–88 years. The average age of those with complicated disease was 45.3 years. The median was 44.0 (SD: 19.2). Therefore, the age range of the severe cases corresponded to the age range of the total cases. The mean and median of the severe cases were only slightly higher than those of the total cases. However, when examining the age distribution of only non-severe malaria patients, significant differences were found: with 36.9 years, the average age of the non-severe cases was significantly lower than the average age of the severe cases. In addition, the patients with uncomplicated malaria had a smaller age range: 18–66 years (see Figure 9 [Fig. 9]).

Figure 9: Age distribution of the total cases, non-severe cases and severe cases

To check whether there was a relationship between age and disease course, a Fisher’s exact test was performed. When creating a crosstab with age (“45 years or younger” and “over 45 years”) and disease course and performing a Fisher’s exact test, the p-value was 0.030 (see Table S25 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). The test therefore showed a significant connection between the age and the course of the disease.

Of the 17 patients with complicated malaria, five patients had a co-infection. Nine people had no co-infection, and no data was available in three cases (see Table S26 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). Among the reported co-infections were two COVID-19 infections, one rhinitis, one mastoiditis and one osteomyelitis.

In order to examine whether there was a connection between co-infection and disease course, a Fisher’s exact test was performed. When creating a crosstab with co-infection (“co-infection” and “no co-infection”) and disease course and performing a Fisher’s exact test, the p-value was 0.713 (the null hypothesis was retained) (see Table S27 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). Therefore, no relationship between co-infections and disease course could be identified.

3.14 Medication

Treatment data was available for 40 of the 44 malaria cases diagnosed at the Institute for Laboratory Medicine at the Northwest Medical Centre.

Atovaquone/proguanil was used in 25 cases, accounting for 62.5% of all cases for which treatment data was available. It was the most often used antimalarial drug in this study. This was followed by artemether/lumefantrine, which was used in 12 cases and thus in 30.0% of all patients. Artesunate was used ten times and thus in 25.0% of all cases, usually with subsequent treatment with atovaquone/proguanil or artemether/lumefantrine. Chloroquine and doxycycline were also used (twice each), usually as an adjunct to treatment. No patient was treated with dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine, although it is also recommended in the DTG guideline. Primaquine was the only drug used against hypnozoites (four cases).

Of the six cases with malaria tertiana, four were treated with atovaquone/proguanil. One of the patients who were treated with atovaquone/proguanil also received chloroquine. One patient was treated with chloroquine only, another patient with artemether/lumefantrine. Information on prophylaxis against relapses was available for four of the six patients. All four patients received primaquine against the hypnozoites.

Of the 37 cases with malaria tropica, data on treatment was available for 34 cases. A total of 17 cases of non-severe malaria tropica were diagnosed at the Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre. Of those 17 cases, 13 patients (76.5%) were treated with atovaquone/proguanil and four patients (23.5%) with artemether/lumefantrine.

Ten of the 17 patients with severe disease were treated with artesunate. Two people were also given doxycycline in addition to therapy. Of the patients treated with artesunate, six (60%) received follow-up treatment with atovaquone/proguanil and two (20%) with artemether/lumefantrine. One person did not receive follow-up treatment and for another person, no information on subsequent treatment was available (see Table S28 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]).

Seven patients who met the criteria for severe malaria did not receive artesunate. Instead, five of these people were given artemether/lumefantrine and two were given atovaquone/proguanil (see Table S29 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]).

When malaria treatment over the course of time was examined, there was a noticeable increase in the administration of artemether/lumefantrine. While artemether/lumefantrine was not administered in the period of 2003–2012, it was already used in 44.4% of all cases (with available data on treatment) in the second half of the observation period. Accordingly, there is a decreasing trend in the use of atovaquone/proguanil: While atovaquone/proguanil was the only medication administered in the first half of the observation period, it was only used in 44.4% of all patients in the second half (see Table S30 in Attachment 1 [Att. 1]).

The increasing use of artemether/lumefantrine also became apparent when the treatment of uncomplicated malaria tropica was examined over the course of time (see Figure 10 [Fig. 10]).

Figure 10: Treatment of the cases with non-severe malaria tropica over the course of time

While from 2003 to 2014 all cases of uncomplicated malaria tropica were treated with atovaquone/proguanil, in the period of 2015–2022 most cases were treated with artemether/lumefantrine (four of the five non-severe cases since 2015).

4 Discussion

The purpose of this research was to analyse the malaria cases diagnosed at the Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre in order to achieve a better understanding of travel-related malaria in Frankfurt am Main and the Rhine-Main area. This study provides valuable insights into the patterns and trends of imported malaria within this region.

4.1 Limitations and considerations

This study was largely based on the evaluation of medical reports. These have the advantage that they contain detailed information regarding disease course and treatment. One disadvantage, however, is that they are less standardized than a questionnaire. As a result, certain information such as prophylactic behaviour or country of origin was often not listed. Since the study included a total of 44 cases, these missing details led to a relatively small sample size when certain characteristics were analysed.

The Robert Koch Institute regularly publishes data on the most important epidemiological characteristics of imported malaria, such as age and gender distribution, Plasmodium species, or countries of infection. But they do not regularly publish data for all characteristics examined in this study, like prophylactic behaviour or trends in medication. In these cases, other publications were used as comparison.

In its epidemiological yearbooks, the RKI states that its statistics only include reported cases that were resident in Germany [7]. However, this study also included cases in which the patient resided abroad, which could slightly limit comparability. However, the number of these cases was small, so a significant influence can be ruled out.

4.2 Case numbers

Of the 44 cases diagnosed between 2003 and 2022, half of the cases occurred in the last six years of the study period, despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Probable causes are increased travel and migration flows as a result of globalisation, whose effects could be further enhanced by the proximity to the airport. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that the year with the highest annual number of cases was 2021, a year when travel restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic were in effect. While the cases decreased in Hesse and in Germany as whole during the pandemic, this was not the case in the Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre. During the pandemic years, a particularly high number of cases were diagnosed compared to the rest of Hesse, with the laboratory accounting for a high proportion of the cases in this federal state (15.0% in 2020 and 15.8% in 2021). One reason for the high case numbers in 2020/2021 could be the demographic profile of Frankfurt. The large proportion of city residents with migration background is also reflected in the results of this study: At least 54.5% of the patients whose purpose of travel was known were VFR, and at least 21 out of the 44 patients had a foreign background. People with foreign backgrounds may have been more willing to travel during the pandemic compared to those with no connection to foreign countries. This could have led to a comparatively high number of cases despite the pandemic.

During the years 2014 and 2015, Germany experienced a significant increase in case numbers. Vygen-Bonnet and Stark attribute this rise to the increased arrival of refugees from malaria-endemic countries [9]. The RKI also reported an increase in P. vivax infections in 2014/2015, which was mainly caused by Eritrean refugees [9]. However, the Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre detected neither a rise in the number of cases nor an increased number of P. vivax diagnoses. This suggests that comparatively few refugees were tested for malaria in the Laboratory Institute. A possible reason for this could be the location of the Northwest Medical Centre. Newly arrived refugees probably moved mainly between Frankfurt’s transport hubs, such as the airport or the main train station, to get to the respective reception facilities. The Northwest Medical Centre, which accounts for the largest proportion of cases in this study, is located relatively on the outskirts of Frankfurt and is more difficult to reach by public transport. Therefore, it could have been visited less frequently by this group of people. The Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre also had no contracts, for example with emergency shelters, to provide laboratory medical care to refugees. It is likely that other laboratories with such contracts had significantly more often refugees as patients. Another factor could be that the small number of cases diagnosed in the Laboratory Institute did not accurately reflect the situation (2014: 23 suspected cases, four positive cases; 2015: 25 suspected cases, 0 positive cases).

4.3 Age and gender

Similar to the RKI data, the age group of 20- to 49-year-olds made up the largest percentage of cases. Individuals in this age group have the highest travel mobility due to their fitness levels and financial means. However, there are differences in the gender distribution. While women accounted for slightly less than a third of the total cases in Germany, the gender ratio in this study was almost balanced. One reason for the different gender distribution could be the high percentage of VFRs (54.5%). The demographic profile of the VFR group might differ from those visiting malaria-endemic regions for tourism. Additionally, VFRs exhibit different travel and prophylactic behaviours compared to non-VFRs [4], [8], which might result in a higher rate of malaria infection among women in this group.

4.4 Plasmodium species

The percentages of the different Plasmodium species largely corresponded to those of the RKI. Although P. vivax, P. ovale, and mixed infections accounted for only a small number of cases, limiting comparability, their percentages were generally consistent with the RKI data. In this study, P. falciparum showed a slightly higher percentage than in the national reporting data, but it was – as in the RKI data – by far the most common species. Since an infection with P. falciparum can rapidly become life-threatening [7], prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential.

4.5 Regions of infection

Most cases diagnosed in the Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre were imported from Africa. This also corresponds to the data from the RKI. The countries most frequently mentioned in our study (Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria and Togo) are regularly listed by the RKI among the most common infection countries. These countries are located either in Central or West Africa, which is why the largest proportion of cases diagnosed in the Laboratory Institute were imported from this region.

All of the three infections originating from Asia were caused by P. vivax. This is consistent with the fact that P. vivax is more widespread outside of Africa: From 2003 to 2022, P. vivax accounted for a maximum of 2.9% of the annual cases in the WHO African Region, while in the WHO South-East Asia Region it had an annual share of 34.3–53.7%. In the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (including Pakistan), P. vivax had an annual percentage of 17.7–39.2% and in the WHO Western Pacific Region (including China) 13.5–35.9% [2].

In October 2019, two cases of airport-associated malaria were diagnosed at the Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre. There were no other cases of airport malaria in Germany that year [32]. According to Wieters et al., both patients had worked in the same service hall at Frankfurt Airport and probably had the same source of infection [14]. For laboratories located in the proximity of airports, malaria plays a particular important role and should always be considered in patients with a fever of an unknown origin.

4.6 Nationality and country of origin

Among the cases where the country of origin was specified, two patients (8.7%) were of German origin and 21 patients (91.3%) were of foreign origin. However, people of German origin could have been underrepresented here, as the country of origin is not required to be stated in the medical report and is often only provided as additional information. For people of German origin, providing this information may often not be perceived as necessary. Nevertheless, it can be stated that at least 21 people, and thus almost half of the people treated, were of foreign origin. The number was probably even higher since information on origin was only available for just over half of the cases. The high number of people with a foreign background was also consistent with the finding that some of the patients had a foreign nationality (31.4%). There are no data on SurvStat@RKI or in the RKI’s epidemiological yearbook regarding the countries of origin. However, one issue of the “Epidemiological Bulletin”, a journal of the RKI, reports on malaria cases from 2021. It states that for the cases reported in 2021, 42% had Germany as their country of origin, while 58% had a different country of origin [38].

4.7 Chemoprophylaxis

Nine of the ten people with information about chemoprophylaxis had not taken any chemoprophylaxis at all or had not taken it consistently. One person reported that they had taken chemoprophylaxis, but there was no information about the type of medication taken or the dosing regimen. Therefore, it was not possible to check whether the medication was suitable for the travel destination and whether it was taken correctly. The low use of prophylactic measures among infected patients was observed in other studies as well: Vygen-Bonnet and Stark, who analysed the German surveillance data regarding malaria from 2001 to 2016, stated that only 24.3% of the cases with data about prophylactic behaviour had reportedly taken any type of chemoprophylaxis [9]. The fact that chemoprophylaxis was taken in only a few malaria cases proves that prophylactic medication rarely fails when taken correctly. At the same time, the high proportion of neglected chemoprophylaxis highlights the importance of travel medical advice and education with respect to chemoprophylaxis for travellers to high-risk areas.

4.8 Reasons for travel

When it comes to travel reasons, VFR had the largest share with 54.5%. A reason for the high share of VFRs could be the high proportion of people with a foreign background in Frankfurt/Main. VFRs are often people who are visiting their former homeland. This group is particularly at risk due to their tendency to travel for long periods, less frequent use of travel medical advice, and generally lower risk awareness regarding malaria. They are also often unaware of their decreasing level of semi-immunity [4], [8]. The fact that more than half of the cases were from the VFR group shows the need to promote travel medical advice for this group. This particularly applies to cities like Frankfurt am Main, which has many residents with foreign backgrounds who might visit friends and relatives in their former homeland.

4.9 Treatment

Atovaquone/proguanil was the most commonly used drug for both malaria tertiana and uncomplicated malaria tropica. It was also the most used follow-up treatment for complicated malaria tropica. However, it had a decreasing trend over the observed period.

While it was not used as frequently as atovaquone/proguanil, an increasing trend could be observed for artemether/lumefantrine. The trend was also reflected in changes of the DTG guideline. In the guideline from 08/2014, atovaquone/proguanil, artemether/lumefantrine and dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine are listed as equally suitable for the treatment of non-severe malaria tropica [39]. In the guideline from 07/2016, these drugs are still described as equally suitable, but it is emphasised that in cases of high parasitaemia, artemisinin-based combination therapy should be preferred due to its faster onset of effect [40]. In the 02/2021 version of the guideline (the latest approved version during the study period), artemether/lumefantrine and dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine are listed as first-choice medications for the treatment of malaria tropica. Atovaquone/proguanil is only listed as an alternative [41].

Despite the fact that dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine is also recommended for the treatment of malaria tropica and malaria tertiana [35], no patient was treated with this medication during the study period. This is likely because dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine has been unavailable or only had limited availability in Germany in recent years [35].

Seven of the 17 people who met the criteria for severe malaria did not receive artesunate, although it is recommended by the DTG guideline [35]. Six of these seven cases that did not receive artesunate were diagnosed after 2014. Artesunate was already recommended in the DTG guideline of 08/2014 as the medication of choice for severe malaria [39]. One reason for not administering artesunate could be that the overall condition of these patients may have been stable despite fulfilling individual criteria. Another possible factor is the former legal situation regarding the administration of artesunate. Although artesunate has long been recommended for the treatment of complicated malaria [39], [40], [41], it was not approved in Germany for a long time. It was not until 2021 that a drug (Artesunate AMIVAS) was approved by the European Medicines Agency [35]. Whether the increased legal clarity will lead to a more frequent use of artesunate in severe malaria cases could be investigated in a follow-up study in a few years.

4.10 Laboratory results

The laboratory measurements with the highest percentages (>90%) were “increased CRP”, “increased PCT”, “anaemia” and “thrombocytopenia”. “Hyperbilirubinaemia” and “elevated LDH levels” also had high percentages (>65%). “Leukocytopenia”, “increased creatinine levels”, “decreased potassium” and “decreased sodium” had percentages of about 50%. CRP and PCT are inflammatory markers that are typically elevated in malaria. Thrombocytopenia and leukopenia are also common manifestations of malaria. LDH and bilirubin are typical haemolysis markers that increase due to plasmodium-induced haemolysis, while haemoglobin levels decrease [41], [42]. A significant association was detected between elevated creatinine and the occurrence of severe malaria. This showed that patients with severe disease often had kidney involvement, even if the creatinine values were usually not above the DTG-defined value of 2.5 mg/dL. In addition, a significant association was found between elevated LDH and a complicated course of the disease.

4.11 Cases of severe disease

Of the 44 patients, 38.6% had a severe course of the disease. The RKI has not published data regarding disease course in malaria patients. A study that examined malaria patients in a tertiary care centre determined a share of 32% [11]. A dissertation that dealt with malaria in returning travellers at a centre of tropical medicine found that 16.3% of the cases had complicated disease [10]. The observation that more than a third of the patients in this study had a complicated disease course indicates that even in a developed country such as Germany there is a need for improvement in the care of malaria patients. Since early diagnosis and treatment can often prevent serious disease, it is crucial to provide ongoing training for physicians in the management of returning travellers with a febrile illness and to ensure these physicians are kept informed of the latest DTG guideline.

The criterion of parasitaemia >5% was by far the most frequently met criteria, with more than a half of the patients showing this symptom. “Disturbances of consciousness and seizures” and “bilirubin >3 mg/dL with parasitaemia >100,000/µL” each occurred in over a third of the cases with severe malaria. The disturbances of consciousness varied in severity. Some patients had “milder” disturbances of consciousness, such as confusion or dizziness, while others were somnolent or even comatose. Seizures were reported in two cases. The fact that renal insufficiency was reported in 35.3% of complicated cases is consistent with the observation that many complicated cases had elevated creatinine levels. However, a creatinine value above 2.5 mg/dL, as defined in the DTG-criteria, occurred in only one person. In addition, exsiccosis occurred in about a third of the severe cases. Fluid loss due to fever (sweating), diarrhoea, vomiting and renal insufficiency might have played a role here.

Patients over 45 years of age experienced severe disease significantly more often. A significant connection between disease severity and age has also been observed in other studies [10], [11]. One reason could be declining immunity in old age. No significant association was found between gender or the presence of co-infections and severe disease. Concerning co-infections, this likely depends on the type of pathogen that causes the co-infection. A separate analysis based on the type of co-infection would be more insightful if the sample size is sufficient.

Among the severe cases, there were also two co-infections with COVID-19. It is not certain to what extent COVID-19 impacted the severity of the disease in these two cases. However, the reports stated that both patients went into quarantine and were only admitted to hospital when their condition worsened. Therefore, there is a real possibility that the malaria diagnosis was delayed because the COVID-19 infection was wrongly considered to be the sole cause of the symptoms.

4.12 The location in Frankfurt am Main

Our research delivers new findings concerning imported malaria in the area around Frankfurt/Main. It would be beneficial to compare the results of this study with data from laboratories or hospitals in other regions. Especially the comparison with facilities that are not located close to an airport or whose region differs in terms of demographics and origin of their residents would provide interesting insights. Unfortunately, there are only few other studies that deal with malaria cases in returning travellers [10], [11]. Therefore, it would be advantageous if more German hospitals or laboratories investigated imported malaria in their facilities to determine regional differences. It would also be interesting to repeat this study in the Laboratory Institute of the Northwest Medical Centre in a few years. This would make it possible to determine whether certain trends, such as increasing case numbers or the changes in medication administration, continue.

5 Conclusions

This study provides significant insights into travel-associated malaria in Frankfurt am Main and the Rhine-Main area. Many findings of this study correspond with the German surveillance data from the Robert Koch Institute, such as the age distribution, the proportions of the Plasmodium species, or the shares of the different countries of infection. But there are also some interesting differences, for example in the gender distribution or the high number of malaria cases in the Laboratory Institute during the COVID-19 pandemic. Another special aspect are the two cases of airport-associated malaria, which rarely occurs in Germany.

Most of the infections were acquired in Africa. P. falciparum was the most common pathogen and was responsible for all cases of severe disease. In terms of treatment, there is evidence that artemether/lumefantrine is increasingly preferred over atovaquone/proguanil due to its faster onset of effect. In severe cases, a significant association with increased creatinine levels and increased LDH levels was found.

The high proportion of severe malaria cases demonstrates that there is still room for improvement in the diagnosis and management of returning travellers, even in a developed country like Germany. It highlights the importance of providing high-quality training for physicians to ensure rapid diagnosis and early initiation of treatment. In addition, increased education for travellers to high-risk areas is necessary, especially since most of the patients had not taken chemoprophylaxis, and many patients were VFR, who have a particular high risk of infection. In cities like Frankfurt am Main, where increased travel traffic and proximity to the airport increase the likelihood of imported tropical infections, these measures are especially important.

More research regarding malaria should be performed at the regional level. Due to globalisation, increased travel, and migration flows, it is likely that the significance of malaria and other travel-related tropical infections will further increase. More studies in this field can reveal regional differences, identify opportunities for improvement in patient care, and raise malaria awareness among medical personnel and travellers. This can make a significant contribution to reducing life-threatening cases of malaria in Germany.

Notes

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the external cooperating clinics for their invaluable assistance in data collection throughout the course of this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Fischer L, Gültekin N, Kaelin MB, Fehr J, Schlagenhauf P. Rising temperature and its impact on receptivity to malaria transmission in Europe: A systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;36:101815. DOI: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101815[2] World Health Organization. World malaria report 2023. Geneva: WHO; 2023 [cited 2024 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240086173

[3] Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7 ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.

[4] Piperaki ET, Daikos GL. Malaria in Europe: emerging threat or minor nuisance? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(6):487-93. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.023

[5] Falkenhorst G, Enkelmann J, Faber M, Brinkwirth S, Lachmann R, Bös L, Frank C. Zur Situation bei wichtigen Infektionskrankheiten – Importierte Infektionskrankheiten 2022. Epid Bull. 2023;46:3-20. DOI: 10.25646/11768.2

[6] Kurth F, Develoux M, Mechain M, Malvy D, Clerinx J, Antinori S, Gjørup IE, Gascon J, Mørch K, Nicastri E, Ramharter M, Bartoloni A, Visser L, Rolling T, Zanger P, Calleri G, Salas-Coronas J, Nielsen H, Just-Nübling G, Neumayr A, Hachfeld A, Schmid ML, Antonini P, Lingscheid T, Kern P, Kapaun A, da Cunha JS, Pongratz P, Soriano-Arandes A, Schunk M, Suttorp N, Hatz C, Zoller T. Severe malaria in Europe: an 8-year multi-centre observational study. Malar J. 2017 Jan 31;16(1):57. DOI: 10.1186/s12936-016-1673-z

[7] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2022. Berlin; 2024 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/11825

[8] Monge-Maillo B, López-Vélez R. Migration and Malaria in Europe. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2012;4(1):e2012014. DOI: 10.4084/MJHID.2012.014

[9] Vygen-Bonnet S, Stark K. Changes in malaria epidemiology in Germany, 2001-2016: a time series analysis. Malar J. 2018;17:28. DOI: 10.1186/s12936-018-2175-y

[10] Breuer R, Richter J, Höhn T. Malaria bei Reiserückkehrern in einem tropenmedizinischen Zentrum in Deutschland [dissertation]. Düsseldorf: Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek der Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf; 2018 [cited 2025 Jan 16]. Available from: https://docserv.uni-duesseldorf.de/servlets/DerivateServlet/Derivate-50794/Dissertation.pdf

[11] Rabe C, Paar WD, Knopp A, Münch J, Musch A, Rockstroh J, Martin S, Sauerbruch T, Dumoulin FL. Malaria in der Notaufnahme. Ergebnisse der Notfallbehandlung bei 137 Patienten mit symptomatischer Malaria [Malaria in the emergency room. Results of the emergency treatment of 137 patients with symptomatic malaria]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2005 Jan 28;130(4):145-9. German. DOI: 10.1055/s-2005-837386

[12] Stadt Frankfurt am Main: Bürgeramt, Statistik und Wahlen. Ausländerinnen und Ausländer 2022: Anteil der ausländischen Bevölkerung zum 31. Dezember 2022 auf 31,3 Prozent gestiegen. Statistik Aktuell. 2023;04. Available from: https://statistikportal.frankfurt.de/download/FSA/2023/FSA_2023_04_Auslaender_Ende_2022.pdf

[13] FRAPORT. Fraport-Verkehrszahlen 2022: Dynamisches Wachstum verdoppelt Passagieraufkommen in Frankfurt. 2023 Jan 16 [cited 2025 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.fraport.com/de/newsroom/pressemitteilungen/verkehrszahlen/q4/verkehrszahlen-2022.html

[14] Wieters I, Eisermann P, Borgans F, Giesbrecht K, Goetsch U, Just-Nübling G, Kessel J, Lieberknecht S, Muntau B, Tappe D, Schork J, Wolf T. Two cases of airport-associated falciparum malaria in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, October 2019. Euro Surveill. 2019 Dec;24(49):1900691. DOI: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.49.1900691

[15] Robert Koch-Institut. SurvStat@RKI 2.0. 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 8]. Available from: https://survstat.rki.de

[16] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2003. Berlin; 2004 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3275

[17] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2004. Berlin; 2005 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3277

[18] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2005. Berlin; 2006 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3279

[19] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2006. Berlin; 2007 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3281

[20] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2007. Berlin; 2008 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3284

[21] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2008. Berlin; 2009 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3286

[22] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2009. Berlin; 2010 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3289

[23] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2010. Berlin; 2011 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3291

[24] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2011. Berlin; 2012 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3293

[25] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2012. Berlin; 2013 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3295

[26] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2013. Berlin; 2014 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3297

[27] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2014. Berlin; 2015 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3299

[28] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2015. Berlin; 2016 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3301

[29] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2016. Berlin; 2017 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/3302

[30] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2017. Berlin; 2018 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/5820

[31] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2018. Berlin; 2019 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/6013

[32] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2019. Berlin; 2020 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/7575

[33] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2020. Berlin; 2021 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/8766.2

[34] Robert Koch-Institut. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2021. Berlin; 2022 [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/12259

[35] Deutsche Gesellschaft für Tropenmedizin, Reisemedizin und Globale Gesundheit e.V. S1-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie der Malaria [Version 30.04.2025]. Berlin: AWMF; 2025. Available from: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/042-001

[36] McHugh ML. The Chi-square test of independence. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2013;23(2):143-9. DOI: 10.11613/BM.2013.018

[37] Hess AS, Hess JR. Understanding tests of the association of categorical variables: the Pearson chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. Transfusion. 2017;57:877-9. DOI: 10.1111/trf.14057

[38] Falkenhorst G, Enkelmann J. Zur Situation bei wichtigen Infektionskrankheiten – Importierte Infektionskrankheiten 2021. Epid Bull. 2022;44:10-4. DOI: 10.25646/10754

[39] Deutsche Gesellschaft für Tropenmedizin, Reisemedizin und Globale Gesundheit e.V. S1-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie der Malaria [Version August 2014]. Berlin: AWMF; 2014. Available from: https://www.aerztenetz-bad-berleburg.de/images/S1-Leitlinie-Diagnostik-und-Therapie-der-Malaria-2014-08.pdf

[40] Deutsche Gesellschaft für Tropenmedizin, Reisemedizin und Globale Gesundheit e.V.. Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie der Malaria [Version Juli 2016]. Berlin: AWMF; 2016. Available from: https://www.dtg.org/images/Leitlinien_DTG/Leitlinie_Malaria_2016.pdf

[41] Deutsche Gesellschaft für Tropenmedizin, Reisemedizin und Globale Gesundheit e.V.. S1-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie der Malaria [Version Februar 2021]. Berlin: AWMF; 2021.

[42] Mischlinger J, Jochum J, Ramharter M, Kurth F. Malaria und ihre Bedeutung in der Reisemedizin. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2022;147(12):745-55. DOI: 10.1055/a-1661-3783

Attachments

| Attachment 1 | Supplementary tables (Attachment1_lab000050.pdf, application/pdf, 258.97 KBytes) |