[Seroprävalenz des humanen Cytomegalovirus bei Blutspendern]

Abhishri Lakshmi Kamal Kanna 1Aswin Manikandan Mathialagan 1

Subhashini Paari 1

Harish Mardawada 2

1 Pathology Department, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, India

2 Radiology Department, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, India

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung: Bluttransfusionen sind ein wichtiger Bestandteil der medizinischen Behandlung. Andererseits stellen Infektionen im Zusammenhang mit Transfusionen mögliche Risiken dar. Deshalb sind Sicherheitsvorkehrungen bei der Blutentnahme, -verarbeitung und -testung wichtig, um das Risiko von durch Transfusionen übertragbaren Krankheiten zu verringern.

Das Zytomegalie-Virus (CMV) wird durch Bluttransfusionen übertragen und stellt weltweit ein Gesundheitsproblem dar. Die Seropositivitätsraten für CMV liegen in der Bevölkerung zwischen 60% und 100%. Zu den wichtigsten Infektionen bei Immunsuppression gehören CMV.

Die Studie wurde als Reaktion auf die wachsende Nachfrage nach Cytomegalovirus-freien Blutprodukten und zur Bestimmung der Prävalenz von CMV-Antikörpern unter freiwilligenden Blutspendern durchgeführt, weil es in Indien nicht viele derartige Studien gibt.

Methode: Die prospektive Studie wurde in der Blutbank der Pathologieabteilung des Sree Balaji Medical College in Chromepet, Chennai, von 2022 bis 2024 auf der Grundlage des positive Ethikvotums durchgeführt. Es wurden 116 freiwillige Blutspender eingeschlossen.

Die Tests wurden mit dem Chemilumineszenz-Kit zum Nachweis von IgG und IgM durchgeführt.

Ergebnisse: 88 (76,0%) der 116 Spender waren Männer, 28 (24%) Frauen. Das Alter der Blutspender verteilte sich wie folgt: 1,2% waren >40 Jahre, 4,3% 36–39 Jahre, 8,2% 31–35 Jahre, 19,1% 26–30 Jahre und 34,1% 18–20 Jahre alt. 75 Personen wurden positiv und 41 negativ auf IgG getestet, was eine CMV-Gesamtprävalenzrate von 64,6% ergibt. Keiner der 116 Blutspender wies eine CMV-IgM-Antikörperreaktivität auf. Die Prävalenz der IgG-Positivität war bei Personen im Alter von ≥26 Jahren höher. Von den IgG-seropositiven Personen waren 68 (64,76%) männlich und 7 (63,63%) weiblich. Der sozioökonomische Hintergrund bei Positivität war in 40% hoch, in 66,3% mittel und in 100% niedrig.

Schlussfolgerung: Die Prävalenz deutet auf eine endemische Infektion hin, die möglicherweise mit Faktoren wie Alter, Geschlecht und sozioökonomischem Status zusammenhängt. IgM-Anti-CMV-Antikörper waren bei keinem Spender vorhanden. Aufgrund der hohen Kosten und des geringen Vorkommens an IgM-Antikörper-positiven Spendern kann das Screening auf Immunglobulin-M-Anti-CMV Antikörper daher auf Hochrisikorezipienten beschränkt werden. Leukozytendepletierte zelluläre Blutprodukte und die Auswahl von CMV-IgG- und CMV-IgM-negativen Spendern sind zwei prophylaktische Ansätze zur Senkung der Transfusionsübertragung (TT) von CMV. Somit unterstreicht unsere Studie die Bedeutung des CMV-Screenings in Blutbanken, die Notwendigkeit der Bewertung von Risikofaktoren für TT-CMV und die Notwendigkeit von Präventivmaßnahmen.

Schlüsselwörter

Cytomegalie, Blutspender, Seroprävalenz Indien, sozioökonomischer Einfluss

Introduction

Blood transfusions are a vital component of medical treatment. On the other hand, transfusion-transmitted infections (TTI) pose possible risks. Therefore, blood collection, processing, and testing safety precautions to reduce the chance of transfusion-transmitted illnesses are important. The extent to which transfusion-transmitted diseases are a problem in a given country depends on the incidence of certain diseases. Precautions are taken to guarantee that blood transfusion therapy is safe for the intended population.

The cytomegalovirus (CMV), a member of the human herpes virus family, is spread by blood transfusions and is a major global health concern [1]. Seropositivity rates for CMV range from 60% to 100% in the population, making it a ubiquitous agent [2]. Among the most important infections that affect people with immunosuppression is CMV. As in the majority of cases with other herpes viruses, the patients survive their initial infection, while the virus remain dormant in the host for the rest of their lives [1]. However, in immunosuppressed individuals, these viruses can reactivate and cause a variety of clinical symptoms [3]. Rates of transmission from blood components to immunocompromised patients have been observed to reach up to 50% [4]. Therefore, the most effective method to lower the risk of CMV transmission would be to provide high-risk patients with blood products free of CMV.

This study was carried out in response to the growing demand for cytomegalovirus-free blood products and to determine the prevalence of CMV antibodies among consenting blood donors. It is possible to determine the seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus among consenting blood donors, which may be helpful in determining whether CMV screening can shield high-risk individuals from infection. To date, there have been few such studies in India; thus, the current study was conducted to fill this knowledge gap. The results may assist health-sector policymakers and planners developing screening programs.

Aim and objectives

To determine the seroprevalence of CMV among healthy, volunteer blood donors at the blood bank of a tertiary-care center by detecting immunoglobulin G, M and anti-CMV taking socio-economic and clinico-pathological parameters into consideration.

Materials and methods

Study design

This prospective cross-sectional study was carried out at the blood bank of the pathology department of Sree Balaji Medical College in Chromepet, Chennai, over the course of two years, from November 2022 to April 2024. A total of 116 volunteer blood donors were chosen. The ethics committee of Sree Balaji Medical College gave its approval. The minimum sample size required was n=116, as calculated by Dobson’s formula.

Collection of samples and antibody determination

5 mL of blood were extracted from each donor’s collecting bag and inserted into a sterile capped tube. The plasma was then separated and kept until needed, after which it was centrifuged.

IgG- and IgM-detection tests were performed with the chemiluminescence kit Electra (Goa, India).

Results

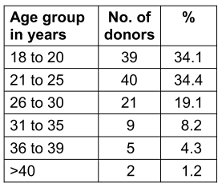

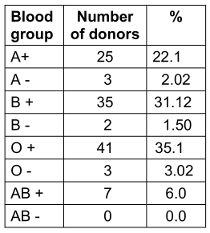

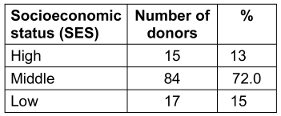

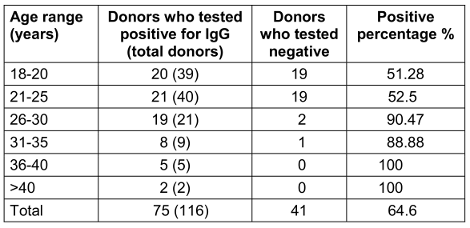

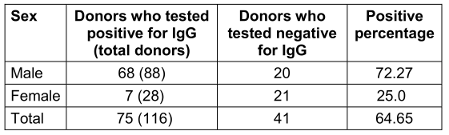

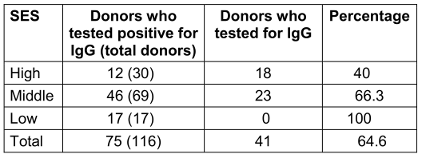

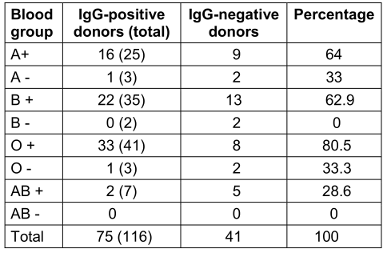

88 (76.0%) of the 116 donors were men, 28 (24%) were women. The age distribution of blood donors is shown in Table 1 [Tab. 1], blood group distribution in Table 2 [Tab. 2], and distribution according to SES in presented in Table 3 [Tab. 3].

Table 1: The study group’s age distribution

Table 2: The blood group’s distribution

Table 3: Distribution according to SES

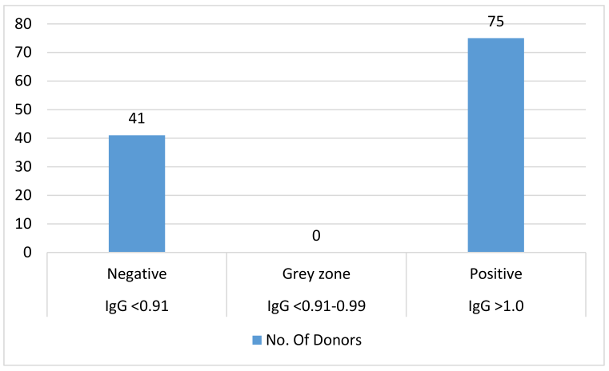

None of the 116 donors tested positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg). Based on IgG titres, 75 of the donors had a history of CMV exposure (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]), but none of the 116 blood donors were positive for IgM or had a indeterminate titre.

Figure 1: Bar diagram of titre results (CMV IgG by CLIA)

Table 4 [Tab. 4] shows an increased prevalence of IgG positivity among individuals aged ≥26 years (p<0.05).

Table 4: Age range of IgG positive individuals

Female were less frequently IgG seropositive (p<0.05) than males (Table 5 [Tab. 5]). The difference in seroprevalence between the sexes was statistically significant (p<0.05).

Table 5: Prevalence of IgG seropositivity by gender

Regarding IgG status, there were statistically significant (p<0.01) differences based on SES (Table 6 [Tab. 6]).

Table 6: Socioeconomic status (SES) of IgG-seropositive donors

There was no discernible relationship found between CMV-IgG seropositivity and blood group (Table 7 [Tab. 7]).

Table 7: Blood groups of IgG-seropositive donors

Discussion

CMV is a beta-DNA herpesvirus carried by almost 90% of the world’s adult population [5].

Given that voluntary blood donors are anticipated to supply the majority of blood transfusion needs, the current study aimed to identify the seroprevalence of CMV infection within this population. Therefore, the current study exclusively included voluntary blood donors because blood donations at our blood center are 100% voluntary.

In comparison with the IgG positivity of other studies, e.g., Seale et al. [6] (57%), Per Ljungman [7] (51.8%), and Amarapal et al. [2] (71%), our study showed 64.6% with positive IgG anti-CMV antibodies, which may indicate that they had previously been exposed. This is comparable with the percentages of industrialized nations.

In agreement with our study, Ibramin et al. [8] also showed that voluntary blood donors were more prevalent in the age groups of 20–40 years and were predominantly male. Many females in our country are anemic, which prevents them from donating blood; this would account for the male predominance among blood donors.

According to the updated Modified Kuppuswamy socioeconomic status scale, our donors were classified as upper, middle, or lower class. The majority of our volunteers (73.0%) were of middle SES, followed by lower SES (14.1%), with the fewest being of SES (13.1%).

An IgG value of <0.91 is considered negative, showiing a lack of previous exposure to cytomegalovirus. If the values are between 0.91 and 0.99 (inconclusive), re-testing is necessary; titre values >1.0 (positive) mean that the donor has had a history of CMV exposure. When the IgM value is <0.90 (negative), it shows a lack of previous exposure to cytomegalovirus. Values between 0.91 and 1.1 (inconclusive) indicate that re-testing is necessary. Titre values >1.1 (positive) show that the donor has had a history of CMV exposure. Based on these values, 75 of 116 donors showed a higher titre value of IgG and 41 showed negative results for IgG. Also, all 116 samples showed a negative titre for IgM.

The IgG anti-CMV antibody test is mainly done to reveal the patient’s past infections.

In our study, IgG serology was positive mostly among donors in their late twenties. Statistically significant differences in CMV IgG status were found between the different age groups (p<0.05). The study by Nikolich-Zurich and van Lier [4], demonstrated that when individuals who are long-time positive for IgG anti-CMV antibodies age, it leads to an increased rate of mortality among these individuals. Another factor that explains these higher death rates is that aging and cytomegalovirus both reduce innate and adaptive immunity, which further enhances the risk of mortality for seropositive individuals as they age [9]. Age-related changes to the T-cell immune system have even been attributed to cytomegalovirus infection as the underlying reason of morbidity [10].

Our study is consistent with research done by Koch et al. [10], who found that as people age, the prevalence of CMV antibodies rises. They reported that the prevalence of the antibody increased from 81% among 21- to 30-year olds to 88% between the ages of 41 to 50 years.

Nearly 30% of our donors in our study were in the age group of 18 to 20 years among them, nearly 50% were IgG positive. This can be reduced by proper guidance on the importance of screening and early detection of cytomegalovirus. Future research should assess exposure and personal behaviour in younger adults prior to a vaccination intended to prevent congenital CMV infection, as half of the young adults in our study had already contracted the virus [11].

Since cytomegalovirus prevalence seems to occur in any age group (younger, middle, or older) and does not seem gender-specific, it is beneficial to include the screening for cytomegalovirus along with other transfusion-transmitted infection screening, so that the recipients of the blood will not contract the virus.

A little over 40% of donors with higher SES tested positive for cytomegalovirus, compared to 66% from middle and 100% from lower SES groups. This concurs with a study done in Finland by Mustakangas et al. [12], which found that seropositivity more frequent in lower socioeconomic groups than in higher socioeconomic groups. According to a study done in Punjab [13], seropositivity decreased as socioeconomic status increased. It is well known that individuals from low socioeconomic backgrounds will have less awareness about the risk of cytomegalovirus transmission, and due to their lifetime exposure to these illnesses, people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to have higher antibody levels [14]. Another study also showed that lower-SES pregnant women from Norway had a higher rate of positive serology for immunoglobulin G cytomegalovirus than did pregnant women with higher SES [15]. Thus, the present study strengthens the evidence that SES plays an important role in the prevalence of cytomegalovirus among the general population. More awareness should be created about screening for cytomegalovirus among the lower SES population. Low SES is associated with increased exposure to cytomegalovirus due to factors such as larger family sizes and living in crowded conditions. Analogous to the literature, this study found no discernible relationship between CMV IgG seropositivity and blood group.

The IgM anti-CMV antibody test is mainly done to determine the presence of an acute infection in the individual. None of the donors in our study had a positive IgM anti-CMV antibody test, proving that there was no initial infection. Our IgM anti-CMV seropositivity rates matched those of studies conducted in Ghana by Adjei et al. [16], in Chandigarh by Pal et al. [17], and in New Delhi by Kothari et al. [18]. In a developing country like India, routine IgM antibody testing may not be possible as the seropositivity rates arevery low, and the cost is high.

In tertiary care hospitals, it is recommended that blood units transfused to newborns, organ transplant recipients, patients with malignancies, and other immunocompromised patients undergo anti-CMV IgM testing or implement preventive strategies to reduce CMV infection.

Due to the high seropositivity of anti-IgG CMV, discarding blood positive for anti-IgG CMV is not feasible, but blood screened positive for anti-IgM CMV is recommended to be discarded.

Out of 116 blood donors in our study, none had a HbAg-positive result. According to a study by Bayram et al. [19], individuals with chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C had a higher incidence of cytomegalovirus infection. Nearly 50% of patients with chronic HBV and 36% of individuals with chronic HCV had evidence of CMV infection.

Blood transfusion has long been cited as a risk of CMV, notably in immunocompromised individuals (e.g., organ transplant recipients) and hospitalized neonates and infants. Nonetheless, the risk of transfusion-transmitted CMV remains contentious, given that a high proportion of the general population is already CMV seropositive, and most infections are asymptomatic.

Donor/recipient CMV serological status remains the main risk factor influencing the incidence and mortality of CMV disease after transplantation. Proper selection of donor and recipient, regular and careful monitoring, early intervention in CMV reactivation, and rapid and effective treatment when the disease develops remain crucial to decreasing the risk of post-transplantation CMV reactivation or disease.

Measures to reduce the risk of TT-CMV have been evaluated in clinical studies, including leucocyte depletion of cellular blood products and/or the selection of CMV-IgG-negative donations.

It is not practical to discard blood that tests positive for IgG anti-CMV antibody due to the 64.6% seropositivity in our study. When seronegative blood is not available, substitutes such as leukoreduced blood products can be used. For individuals who are more susceptible to cytomegalovirus illness, leukoreduced components should nonetheless be utilized less frequently than cytomegalovirus seronegative components when it comes to transfusion requirements.

Conclusion

The high prevalence 64.7% of CMV in our study points to an endemic infection, which was related to factors such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status.

IgM anti-CMV antibodies were absent in every donor. Therefore, because of the high cost and low prevalence of IgM anti-CMV positivity among blood donors, IgM anti-CMV antibody screening can be limited to only high-risk, susceptible recipients.

The prophylactic approaches to lower the seroprevalence of TT-CMV include the use of leukocyte-depleted cellular blood products and the selection of CMV-IgG and CMV-IgM-negative donors for the benefit of the recipients.

Thus, our study highlights the importance of screening for CMV in addition to the routine screening tests at blood banks, the need to assess risk factors for TT-CMV, and the need to take preventive action.

Notes

Ethical approval

The Sree Balaji Medical College’s ethics committee in Chromepet, Chennai, gave its approval.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Singh B, Kataria SP, Gupta R. Infectious markers in blood donors of East Delhi: prevalence and trends. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2004 Oct 1;47(4):477–9.[2] Amarapal P, Tantivanich S, Balachandra K. Prevalence of cytomegalovirus in Thai blood donors by monoclonal staining of blood leukocytes. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001 Mar 1;32(1):148–53.

[3] Messih IYA, Ismail MA, Saad AA, Azer MR. The degree of safety of family replacement donors versus voluntary non-remunerated donors in an Egyptian population: a comparative study. PubMed. 2014 Apr 1;12(2):159–65. DOI: 10.2450/2012.0115-12

[4] Nikolich-Žugich J, van Lier RAW. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) research in immune senescence comes of age: overview of the 6th International Workshop on CMV and immunosenescence. GeroSci. 2017 Jun; 39(3):245–9. DOI: 10.1007/s11357-017-9984-8

[5] Styczyński J. ABC of viral infections in hematology: focus on herpesviruses. Acta Haematol Polon. 2019 Sep 28;50(3):159–66. DOI: 10.2478/ahp-2019-0026

[6] Seale H, MacIntyre CR, Gidding HF, Backhouse JL, Dwyer DE, Gilbert L. National serosurvey of cytomegalovirus in Australia. Clin Vacc Immunol. 2006 Nov 1;13(11):1181–4. DOI: 10.1128/CVI.00203-06

[7] Ljungman P, Brand R. Factors influencing CMV seropositivity in stem cell transplant patients and donors. Haematologica. 2007 Aug 1;92(8):1139–42. DOI: 10.3324/haematol.11061

[8] Ibrahim, Mona Ahmed Ismail, Saad AA, Azer MR. The degree of safety of family replacement donors versus voluntary non-remunerated donors in an Egyptian population: a comparative study. PubMed. 2014 Apr 1;12(2):159–65. DOI: 10.2450/2012.0115-12

[9] Pawelec G, Akbar A, Beverley P, Caruso C, Derhovanessian E, Fülöp T, Griffiths P, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Hamprecht K, Jahn G, Kern F, Koch SD, Larbi A, Maier AB, Macallan D, Moss P, Samson S, Strindhall J, Trannoy E, Wills M. Immunosenescence and Cytomegalovirus: where do we stand after a decade? Immun Ageing. 2010 Sep 7;7:13. DOI: 10.1186/1742-4933-7-13

[10] Koch S, Larbi A, Ozcelik D, Solana R, Gouttefangeas C, Attig S, Wikby A, Strindhall J, Franceschi C, Pawelec G. Cytomegalovirus infection: a driving force in human T cell immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007 Oct;1114:23-35. DOI: 10.1196/annals.1396.043

[11] Wood EK, Reid BM, Sheerar DS, Donzella B, Gunnar MR, Coe CL. Lingering effects of early institutional rearing and cytomegalovirus infection on the natural killer cell repertoire of adopted adolescents. Biomolecul. 2024 Apr 9;14(4):456. DOI: 10.3390/biom14040456

[12] Mustakangas P. Human cytomegalovirus seroprevalence in three socioeconomically different urban areas during the first trimester: a population-based cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2000 Jun 1;29(3):587–91.

[13] Jindal N, Aggarwal A, Sheevani. A pilot seroepidemiological study of cytomegalovirus infection in women of child bearing age. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2005;23(1):34. DOI: 10.4103/0255-0857.13870

[14] Herbert TB, Cohen S. Stress and immunity in humans: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 1993 Jul;55(4):364–79. DOI: 10.1097/00006842-199307000-00004

[15] Odland ML, Strand KM, Nordbø SA, Forsmo S, Austgulen R, Iversen AC. Changing patterns of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence among pregnant women in Norway between 1995 and 2009 examined in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study and two cohorts from Sør-Trøndelag County: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013 Sep;3(9):e003066. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003066

[16] Adjei A, Armah H, Narter-Olaga E. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus among some voluntary blood donors at the 37 military hospital, Accra, Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2006 Sep 1;40(3):99–104. DOI: 10.4314/gmj.v40i3.55261

[17] Pal SR, Chitkara ML, Krech U. Seroepidemiology of cytomegalovirus infection in and around Chandigarh (Northern India). Indian J Med Res. 1972;60:973-8.

[18] Kothari A, Ramachandran VG, Gupta P, Singh B, Talwar V. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus among voluntary blood donors in Delhi, India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2002 Dec 1;20(4):348–51.

[19] Bayram A, Özkur A, Erkilic S. Prevalence of human cytomegalovirus co-infection in patients with chronic viral hepatitis B and C: A comparison of clinical and histological aspects. J ClinVirol. 2009 Jul;45(3):212–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.05.009