[Hebamme werden: Eine qualitative Studie zu den Faktoren, die die Entscheidung für ein Studium der Hebammenwissenschaft beeinflussen]

Oana Gröne 1Ina Mielke 1

Daniela Vogel 2

Mirjana Knorr 1

1 Institute of Biochemistry and Molecular Cell Biology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

2 Academy for Education and Career, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund: Die Professionalisierung der Hebammenausbildung hat in Deutschland zur Einführung von Bachelorstudiengängen geführt. Hebammenstudiengänge ziehen potenziell Bewerbende mit unterschiedlichen Motivationen an. Die Wahl eines Studienprogramms wird maßgeblich durch Motivationsfaktoren beeinflusst, da diese einen Einfluss auf den akademischen Erfolg und die Zufriedenheit der Studierenden haben. Sowohl die intrinsische als auch extrinsische Motivation in einem bestimmten Berufsfeld zu arbeiten, erhöhen die Wahrscheinlichkeit, dass sich eine Person intensiver mit ihrem Studium auseinandersetzt und bessere Ergebnisse erzielt. Daher ist es entscheidend, ein Studienfeld zu wählen, das sowohl persönliche Interessen als auch motivationsfördernde Faktoren berücksichtigt, um einen erfolgreichen akademischen Werdegang zu gewährleisten.

Ziel: Ziel dieser Studie war es, Faktoren zu identifizieren, die die Entscheidung der Studierenden beeinflussen, Hebammenwissenschaft in einer großen deutschen Stadt zu studieren.

Methode: Wir haben einen qualitativen Ansatz genutzt, um die Motivation der Studierenden für das Hebammenstudium zu untersuchen. Hierfür führten wir 23 Interviews mit Erst- und Drittjahres-Studierenden im ersten und dritten Studienjahr mithilfe eines halbstrukturierten Interviewleitfadens. Die Daten wurden anhand der Framework-Analyse ausgewertet.

Ergebnisse: Die Studienteilnehmenden wurden hauptsächlich durch intrinsische Faktoren wie Werte, Emotionen und berufsspezifische Interessen motiviert. Bestimmte Eigenschaften wie Empathie und Resilienz sowie Erfahrungen durch Praktika oder eigene Geburten wurden als entscheidend für die Wahl des Hebammenstudiums angesehen. Obwohl sie bei der Entscheidung, Hebammenwissenschaft zu studieren, eine geringere Rolle spielten, hatten extrinsische Faktoren wie das Ansehen des Berufs und Aspekte des deutschen Gesundheitssystems sowohl eine motivierende als auch eine demotivierende Wirkung.

Schlussfolgerung: Die Dominanz der intrinsischen Motivation unter den Hebammenstudierenden deutet auf ein großes Potenzial für zufriedene Studierende hin. Die Ergebnisse der Studie legen jedoch nahe, dass ungünstige Arbeitsbedingungen die Motivation verringern und möglicherweise zu einem Abbruch führen könnten. Die Studienergebnisse können Lehrende bei der Curriculumsentwicklung und bei Auswahlverfahren unterstützen.

Schlüsselwörter

Hebammenwissenschaft, Motivation, Professionalisierung, Bildung, Verbleib im Beruf

Background

One approach to professionalising midwifery has been through education. Prompted by international regulations and standards, the switch from a vocational qualification to a bachelor’s degree has been implemented at different speeds across European countries [19], [35]. Until 2019, the majority of German midwives still completed their training at vocational training colleges [25]. In fact, Germany was the last EU member state to follow the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommendations [38] concerning the standardisation of midwifery training at university level [5]. Professionalisation and educational reform are therefore still in a transitional period.

Higher education provides midwifery candidates with more career opportunities and potentially contributes to increasing the desirability of midwifery as a degree subject. The attractiveness of programmes is likely to be influenced both by institutional factors, such as having new, up-and-coming educational offerings [2], but mostly by individual factors such as motivation [30]. Motivation for choosing a particular degree subject is a multifaceted construct that distinguishes between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation [20], which are concepts that originate in the theory of self-determination [27]. Intrinsic motivation is the type that is most in line with one’s own interests, whereas extrinsic motivation refers to the extent to which behaviour is influenced by external factors, such as reward structures.

Given that the development of midwifery studies in Germany is only in the early stages, exploring students’ motivation to study the field is extremely relevant to structural curriculum development and selection procedures, which are also at the early stages of development and validation [17]. In some European countries such as the UK, selection procedures are quite diverse and include, among others: knowledge tests, standardised interviews and personal statements or motivation letters [7], [32], [39]. According to an overview provided by the German Midwives Association, entry requirements for midwifery degrees include the successful completion of 12 years of general education (Abitur or Fachabitur) or of a training qualification in healthcare or nursing, the submission of a medical certificate and police clearance certificate, and proof of German language proficiency [10].

Additionally, many universities require the completion of an internship in a relevant field and knowledge or social competency tests [17].

Considering the challenges related to the retention of midwifery students [16], [26] and indeed midwives who are already working [1], it is imperative that in the admission process, universities identify candidates who have the necessary personal characteristics for the job and who are aware of the demanding degree course and working conditions [34]. Previous studies on midwives’ motivation [22], [29], [31] pointed at a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors prompting students’ decisions to apply for a certain degree programme. For example, a desire to help or serve others and an interest in specific areas, such as improving maternal and child health, were common themes across studies. One study conducted in Germany looked at the motivation of students who had enrolled in a bachelor’s programme [6] because of their interest in the field and in research. However, the study was performed with midwives who were already qualified and focused mainly on satisfaction with the professional situation, job development and opportunities, but less on the motivation to study midwifery. In spite of some commonalities in study findings, it is difficult to draw generalisable conclusions related to motivations to study midwifery, mainly due to the diversity of education and healthcare systems, which may themselves result in certain types of motivating factors. Considering context specificity and given that Germany is still in a transitional stage of educational reform and professionalisation of midwifery, the aim of our study was to identify factors that influence students’ decisions to study midwifery in a large German city.

Methods

The current study focuses on understanding meaning. It therefore adopts a qualitative approach in an interpretative paradigm to explore students’ motivation for studying midwifery [23]. Since detailed descriptions of participants’ views on motivation were sought, the use of one-to-one interviews was considered the most appropriate method. We used purposive sampling to recruit participants that could provide crucial information on the subject being investigated [18]. We invited 109 midwifery students via email to participate in our study and we offered them a 25 euro voucher as an incentive to show our appreciation for their time and effort. Soon after receiving the email invitation, 25 students confirmed their interest in being interviewed and 23 ultimately participated in the study. The 23 one-to-one interviews were conducted by three researchers, took place online and had a length of 20 to 30 minutes. Before the interviews, participants were informed of the aims of our research. This was supplemented by an information sheet detailing the expected degree of involvement and an informed consent letter which participants signed before the interview took place. The semi-structured interview guide was developed by our multidisciplinary team of two psychologists, an educationalist and a public health professional. It was based on a literature review about motivation [20], [28] and written feedback from midwives and educators in the midwifery degree programme. It contains questions about personal and general motivation for studying midwifery, as well as questions regarding professional prospects (Attachment 1 [Att. 1]). After the first two interviews, researchers refined and finalised the interview guidelines and concluded that the planned length of the interviews was appropriate. The interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and pseudonymised. As part of meeting quality criteria for qualitative research, participants were given the opportunity to read and make changes to the interview transcripts [24], [33]. Three of the participants were interested in reviewing the transcripts to eliminate any potential misunderstandings. One of them deleted three references to her previous work experience, which could have led to her being identifiable. This did not have any consequences for the coding system or interpretation of data.

The framework analysis method was used to analyse qualitative data [13]. This method is generally characterised by teamwork and some of its procedures are used to ensure transparency. The analysis process combined deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis as the main overarching themes were derived from the research question; additionally, new themes emerged from the qualitative data due to the open-ended nature of the interview questions [15]. The MAXQDA 2022 software assisted the analysis process and management of the collected data. After repeated reading of verbatim transcripts, two researchers coded the first two interviews and identified initial codes, categories and potential themes. At this point, all four co-authors met and agreed on a general coding framework. Subsequently, after coding additional interviews, the two researchers met regularly to discuss and agree on the final coding tree. The codes were then applied to the raw data, a process called indexing in the framework analysis method. Each code was discussed to ensure consistent assignment to the data. During the data analysis process, some quotations were recoded or codes merged because of similarity in content and meaning. Lists of quotations for each code were generated and re-read. Researchers then identified typologies, which are understood as connections between data categories and characteristics, and constitute an important step in the interpretation of the data. A final list of 83 codes, organised into categories and themes, was generated.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

The majority of study participants (65%, n=15) were in the third semester, while the others had just started their studies. Interviewees were female and 27.9 years (SD=6.9) old on average. Most of them had previously started or completed a different university degree (70%, n=16).

Overarching themes

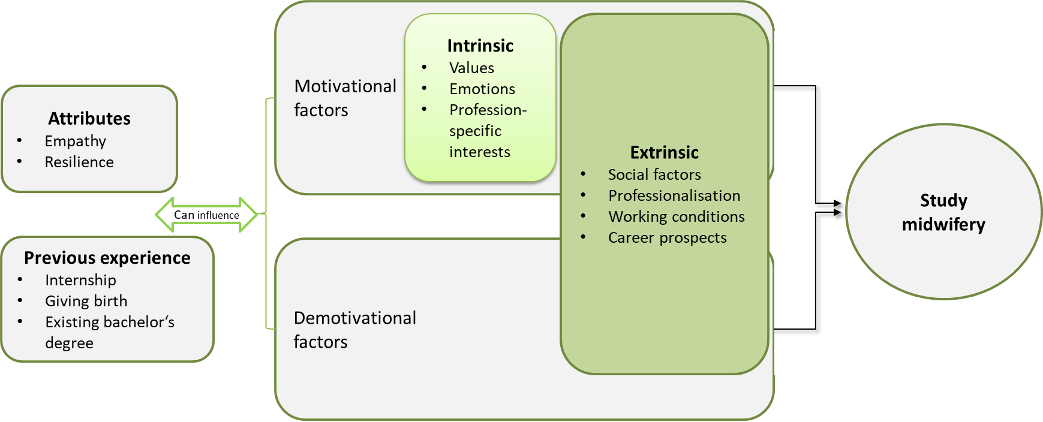

The interviews with the midwifery students aimed at establishing the factors that influenced their motivation for studying midwifery. The findings are organised into four overarching themes: attributes, previous experience, intrinsic, and extrinsic factors. A summary of categories and themes is shown in Figure 1 [Fig. 1], illustrating that the decision to study midwifery is determined by intrinsic and extrinsic (de)motivating factors. As possessing certain attributes and previous professional or personal experience can influence the motivation to study midwifery, the relationship between experience/attributes and motivation can be described as reciprocal. For example, some study participants reported that being motivated had already influenced their decision to do an internship in the field of midwifery, while other interviewees reported having decided to study midwifery after completing an internship or after giving birth.

Figure 1: Factors influencing students’ motivation to study midwifery

Attributes and previous experience

The attributes mentioned most often as being crucial for the midwifery profession were empathy and resilience. Additional attributes emphasised by the interviewees were being well structured, goal oriented, open, tolerant, confident, a good team player, flexible, motivated, self-reflective, patient, intelligent and communicative.

Some interviewees identified previous experience as an important factor determining their motivation to study midwifery. Having completed an internship or university degree and having given birth were some of the experiences mentioned by participants that motivated them to pursue a career in midwifery. Doing an internship before applying for the degree programme was viewed as a trigger but also as a stepping stone in the decision to study midwifery.

For some participants, the motivation to study midwifery was sparked after having started or completed a university degree in a different subject. Reflecting on their initial study choice led to the realisation that it may not be the right path and gave participants the courage and confidence to pursue a career that they love.

Giving birth was described in both a positive and negative light by study participants. Some decided to study midwifery after their own birth experience and having had a positive personal experience with midwives during their maternity leave. On the other hand, some viewed a negative birth experience (not necessarily their own) and the desire to change certain aspects of care as being unrealistic and at the same time a “false” motivator to study midwifery.

I think you first have to deal with your own trauma in a different way before you start the course. It’s a bit like not liking school and then becoming a teacher in order to do it better. That’s a totally honourable motive, but I think maybe it’s just not that realistic.

Intrinsic factors

Most of the aspects influencing students’ decisions to study midwifery were intrinsic in nature. The main intrinsic factors were related to humanistic values, emotions and profession-specific interests. Some of the values that were important to midwifery students were meaningfulness, helping others and empowering women. For most interviewees, the meaningfulness associated with the nature of midwifery work, and the importance of pre- and postnatal care for women’s health played a crucial role in their decision to become midwives. Many also expressed a sense of inevitability, expressing that they “have always known” they wanted to be in a caring profession.

Helping others and supporting women were other essential intrinsic motivators mentioned by the majority of interviewees. A strong sense of female identity and the desire to provide comprehensive healthcare to women and their families was a dominant theme in the interviews.

In this context, some even viewed political engagement as part of their responsibility in the context of the changing midwifery profession and healthcare system. This was mentioned by several interviewees who expressed their wish to make a difference and contribute to the improvement of healthcare.

When asked what motivated them to study midwifery, participants often mentioned emotions and used terms such as “fascination”, “privilege”, “special moment”, or “passion”. Studying midwifery because of a fascination with the female body or with the mother-baby relationship was another motive often raised by study participants.

Students saw being able to work as a midwife as a privilege because of the special role midwives play in counselling and accompanying families in intimate situations. Study participants considered giving birth and starting and adding to a family very special moments that they felt privileged to be part of.

Being passionate about midwifery was viewed as paramount for working in this profession, particularly when considering the challenging working conditions. Studying midwifery as a means of transitioning to a different career was perceived negatively and as unfair by many of the participants interviewed, above all because it results in many other passionate candidates missing out on an opportunity to study midwifery as they are not considered in the admission process.

The motivation to study midwifery was also influenced by interests that are specific to the midwifery profession. Having a practical job as opposed to working in an office was one of the intrinsic motivators named by some of the interviewees.

Some study participants explained that they had opted to study midwifery rather than medicine on account of having more opportunities to guide and support physiological as opposed to pathological processes. Another profession-specific interest mentioned by participants was being able to provide long-term care and the opportunity to care for families for an extended period of time, thus building a stronger partnership with women and their families.

Interviewees were also motivated to study midwifery because of the psycho-social aspects of the profession which involves caring not only for women’s physical but often for their mental health as well. Again, this aspect was sometimes compared to the physician’s role and responsibilities.

The role of a midwife as a knowledge facilitator and a person of trust for women was another intrinsic motivator specific to the midwifery profession. Participants also highly valued the variety of tasks and career opportunities within the profession.

Participants’ decisions to study midwifery was sparked in some cases by an existing interest in the natural and social sciences and medical procedures. Moreover, some students expressed their wish for their work to be guided by evidence-based practice and their intention to pursue a career in research.

Extrinsic factors

The participants in our study mentioned a variety of extrinsic factors related to social elements and developments in the healthcare system, some of which were viewed as both motivating and demotivating. The social factors included the influence of family or friends over the decision to study midwifery, the image of midwives in society, being place-bound, and family and life planning. Some midwifery students felt that midwives were viewed positively in society and highlighted this as a potential motivating factor.

Many interviewees stated that they had not been influenced by family and friends in their decision to study midwifery. However, some admitted that they first considered midwifery at the suggestion of others in their social circle.

In the interviews, participants referred to the healthcare system in Germany, mentioning aspects such as the introduction of university degrees. The professionalisation of midwifery was seen as both a motivating and demotivating factor. On the one hand, it was seen as an opportunity to improve midwives’ new standing in the healthcare system, on the other it was perceived as a barrier for certain groups of applicants due to stricter academic entry requirements.

And something I think is a shame is that fewer people are now being given the opportunity to become midwives. Because now there are simply no more applicants without an Abitur [approximate equivalent to A-levels].

Despite their awareness of the challenging working conditions, students still decided to apply for the midwifery bachelor’s degree programme and become midwives. Interviewees were aware that working shifts could be demotivating and underlined the importance of having a good social network.

In spite of the demotivating aspects related to the working environment in the midwifery profession, such as having to pay high insurance fees and having a low salary, students maintained their motivation to study midwifery and were able to see the advantages rather than just the negative aspects of the profession. At the same time, working in a team was described in both a positive and a negative light because of existing hierarchical structures.

Some study participants were motivated by the career prospects of working as freelance professionals, mainly due to the work–life balance it offered. The reluctance of some of our interviewees to work in a hospital delivery room was mostly prompted by the workload and working environment.

Participants demonstrated a good awareness of the high demand for midwives in the German healthcare system and were concerned about the quality of their work being affected by precarious working conditions.

Finally, Germany was described both positively – as a country with many resources that offers home visits – and negatively – as lacking a women-centred approach and services related to preparation for birth.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to gain insights into what motivated midwifery students in a large German city to choose their degree subject. As the education of midwives in Germany is currently at a turning point, shifting towards becoming a degree programme, a deeper understanding of students’ motivation is crucial for recruitment and selection strategies as well as for ensuring that curriculum goals retain motivated midwives in the future.

Attributes and previous experience

Midwifery students participating in our study underlined the relevance of possessing attributes such as empathy and resilience for the midwifery profession. These findings resonate with the image of the “good midwife” reported in previous research [4], in which study participants similarly emphasised the significance of personal qualities and communication skills.

Interviewees’ past experience was the main determinant in the decision to study midwifery. Previous study or work experience constituted a confirmation or trigger of motivation, a finding that was also observed among Irish nursing students [21]. This finding can support decision-makers involved in selection procedures who may consider midwifery internships a relevant admission criterion.

Experiencing childbirth also stimulated students’ fascination with midwifery and guided their decision to apply for the bachelor’s degree programme, at times also fuelled by a desire to make a difference and contribute to the reform of the midwifery profession. Other studies from Portugal [29] and Australia [9] carried out with young midwifery students found similar results concerning the impact of exposure to childbirth on embarking on a midwifery degree. Unlike their Australian counterparts, some interviewees in our study had reservations about the childbirth experience being the “right” motivator to become a midwife. These findings show a diversity of views which could partly be due to age differences, and which reveals an aspect we did not specifically address in our research.

Intrinsic factors

Our study participants perceived intrinsic motivating factors as most important in their decision to enter midwifery. These results are in line with previous research conducted with midwifery [31], [37], nursing [21], [36] and medical students [14], showing that the desire to help others or the passion for caring were crucial in the decision to pursue the respective careers, which appears to be characteristic of caring professions.

Unlike previous studies with nursing students, who would have chosen medicine if they had had the opportunity to do so [21], our interviewees demonstrated a real passion for the midwifery profession, describing it as their primary career choice. Congruent with a UK-based study [37], our midwifery students clearly stated the reasons why they had chosen midwifery over other health professions such as medicine. This included an opportunity to focus on women’s health (as opposed to disease) and to care for women in a more comprehensive way. A passion for midwifery and a strong sense of professional pride seem to transcend contextual features of healthcare systems, as evidence from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) points to comparable findings [3].

Lastly, and perhaps of most relevance especially in the context of midwifery training being upgraded to a bachelor’s degree programme, the students interviewed in our study were driven to enter midwifery as a result of their interest in science and evidence-based practice. This resembles the results of a systematic review of medical students’ motivation who were equally drawn to science upon entering medicine [14]. Such findings show the potential of the professionalisation of midwifery to strengthen evidence-based practice.

Extrinsic factors

In spite of the predominance of intrinsic motivators, study participants stressed the relevance of extrinsic motivating factors upon entering midwifery. Similar to an Ethiopian study [31], students acknowledged having been inspired by the positive image of midwives in society. As in the case of Ethiopian midwives, the decision to study midwifery was mostly made by the participants alone and had not been influenced by others.

Achieving a work–life balance was also mentioned by the participants, who expressed their intention to shape their careers so as to be able to accommodate family commitments. The role of working conditions and supportive environments were previously found to represent a challenge to the retention of midwives. German midwives who had enrolled in a midwifery bachelor’s programme in one region stated that their primary motivation to study for a degree (despite already having qualified as midwives through vocational training) was the current situation in midwifery, the low wages and poor career prospects [6]. Similarly, Australian midwifery students’ lack of motivation to work in the continuity of care was due to unsupportive workplace cultures [8]. The introduction of bachelor’s degrees may contribute to achieving more autonomy and perhaps a more established role for midwives in the healthcare system, as new generations of midwifery students are increasingly committed to political and cultural change.

Limitations and future directions

Our study has a number of limitations. First, we only interviewed students that had been admitted to university. Future studies could investigate whether candidates that were not successful in the selection process may have had a different motivation to study midwifery.

Furthermore, researchers could focus on exploring the demotivating factors in students who were interested in midwifery, did midwifery internships but eventually decided not to apply for a bachelor’s programme in the field.

Our study participants were in the first and third semester. Students’ motivation is known to decrease with time, therefore an investigation of how motivation progresses until degree completion and beyond should be examined. Moreover, participants were homogeneous in that 70% of them had already finished an academic degree (and were therefore also older), which could influence the results, particularly concerning the role of previous experience as a motivating factor. Future research should therefore explore the role of age and previous academic experience in the decision to study midwifery.

Finally, given that the interviewers are members of admissions teams, social desirability bias may have had an impact on our research. However, the students we interviewed had already been admitted to the midwifery programme and were transparent in their answers, mentioning for example both the advantages and the disadvantages of the professionalisation of midwifery.

Practical implications

Our study results suggest a predominance of intrinsic motivation among midwifery students, which points to enormous potential for successful and satisfied midwives. However, national [1] and international [34] healthcare systems suffer from an acute shortage of midwives and struggle to fill midwifery positions, probably because the unfavourable working conditions reduce motivation over time. Therefore, investigating students’ motivation to study midwifery is central to the development of selection or screening tools that can predict the attrition and retention of students [11], [12]. It is recommended that admission stakeholders use standardised interviews addressing motivation as a selection tool and make the existence of practical experience a requirement, indicating students’ interest in the midwifery profession. Finally, the findings of the current study can help educators to improve the curriculum in order to increase student satisfaction and the likelihood of retention, namely by aligning the content and requirements of the study programme with students’ expectations and motivation to study midwifery.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Albrecht M, Loos S, an der Heiden I, Temizdemir E, Ochmann R, Sander M, Bock H. Stationäre Hebammenversorgung. Berlin: IGES Institut GmbH; 2019.[2] Arpan LM, Raney AA, Zivnuska S. A cognitive approach to understanding university image. Corp Commun. 2003;8(2):97-113. DOI: 10.1108/1356328031047535

[3] Bogren M, Grahn M, Kaboru BB, Berg M. Midwives' challenges and factors that motivate them to remain in their workplace in the Democratic Republic of Congo-an interview study. Hum Resour Health. 2020 Sep;18(1):65. DOI: 10.1186/s12960-020-00510-x

[4] Borrelli SE. What is a good midwife? Insights from the literature. Midwifery. 2014 Jan;30(1):3-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.06.019

[5] Bovermann Y. Akademisierung des Hebammenberufs (Teil 1): Chancen – und wie sie in den Studiengängen bestmöglich genutzt werden können [The Shift to Academic Degree Level of the Midwifery Profession (Part 1): Opportunities - and how they can be used in the Best Possible Way In The Study Programmes]. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2020 Jun;224(3):124-9. DOI: 10.1055/a-1124-9760

[6] Butz J, von Kolontay K, Wangler S, Wiechmann S. Zur Studienmotivation unter Hebammen: Ergebnisse einer Evaluierung. Hebammenforum. 2018;8:905-7.

[7] Callwood A, Groothuizen JE, Lemanska A, Allan H. The predictive validity of Multiple Mini Interviews (MMIs) in nursing and midwifery programmes: Year three findings from a cross-discipline cohort study. Nurse Educ Today. 2020 May;88:104320. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104320

[8] Carter J, Sidebotham M, Dietsch E. Prepared and motivated to work in midwifery continuity of care? A descriptive analysis of midwifery students' perspectives. Women Birth. 2022 Mar;35(2):160-71. DOI: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.03.013

[9] Cullen D, Sidebotham M, Gamble J, Fenwick J. Young student's motivations to choose an undergraduate midwifery program. Women Birth. 2016 Jun;29(3):234-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.10.012

[10] Deutscher Hebammenverband. Wie werde ich Hebamme? Zugangsvoraussetzungen und Bewerbung. 2023. Available from: https://hebammenverband.de/hebamme-werden-und-sein/das-studium

[11] Eley D, Eley R, Bertello M, Rogers-Clark C. Why did I become a nurse? Personality traits and reasons for entering nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2012 Jul;68(7):1546-55. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05955.x

[12] Fowler J, Norrie P. Development of an attrition risk prediction tool. Br J Nurs. 2009;18(19):1194-200. DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2009.18.19.44831

[13] Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013 Sep;13:117. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

[14] Goel S, Angeli F, Dhirar N, Singla N, Ruwaard D. What motivates medical students to select medical studies: a systematic literature review. BMC Med Educ. 2018 Jan;18(1):16. DOI: 10.1186/s12909-018-1123-4

[15] Gray DE. Doing research in the real world. 3rd ed. London: Sage; 2014.

[16] Green S, Baird K. An exploratory, comparative study investigating attrition and retention of student midwives. Midwifery. 2009 Feb;25(1):79-87. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2007.09.002

[17] Groene OR, Knorr M, Vogel D, Hild C, Hampe W. Reliability and validity of new online selection tests for midwifery students. Midwifery. 2022 Mar;106:103245. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.103245

[18] Hesse-Biber SN, Leavy P. The practice of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2011.

[19] James HL, Willis E. The professionalisation of midwifery through education or politics? Aust J Midwifery. 2001;14(4):27-30. DOI: 10.1016/s1445-4386(01)80010-0

[20] Janke S, Messerer LAS, Merkle B, Krille C. STUWA: Ein multifaktorielles Inventar zur Erfassung von Studienwahlmotivation. Z Pädagog Psychol. 2021;37(3):1-17. DOI: 10.1024/1010-0652/a000298

[21] Mooney M, Glacken M, O'Brien F. Choosing nursing as a career: a qualitative study. Nurse Educ Today. 2008 Apr;28(3):385-92. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2007.07.006

[22] Moores A, Catling C, West F, Neill A, Rumsey M, Samor M, Homer CS. What motivated midwifery students to study midwifery in Papua New Guinea? Pac J Reprod Health. 2015;1(2):60-7. DOI: 10.18313/pjrh.2016.920

[23] Morgan DL. Paradigms Lost and Pragmatism Regained: Methodological Implications of Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. J Mix Methods Res. 2007;1(1):48-76. DOI: 10.1177/2345678906292462

[24] O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014 Sep;89(9):1245-51. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

[25] Plappert C, Graf J, Simoes E, Schönhardt S, Abele H. The Academization of Midwifery in the Context of the Amendment of the German Midwifery Law: Current Developments and Challenges. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2019 Aug;79(8):854-62. DOI: 10.1055/a-0958-9519

[26] Rodgers S, Stenhouse R, McCreaddie M, Small P. Recruitment, selection and retention of nursing and midwifery students in Scottish Universities. Nurse Educ Today. 2013 Nov;33(11):1301-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.02.024

[27] Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000 Jan;25(1):54-67. DOI: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

[28] Sekhar C, Patwardhan M, Singh RK. A literature review on motivation. Glob Bus Perspect. 2013;1(4):471-87. DOI: 10.1007/s40196-013-0028-1

[29] Sim-Sim M, Zangão O, Barros M, Frias A, Dias H, Santos A, Aaberg V. Midwifery now: Narratives about motivations for career choice. Educ Sci. 2022;12(4):243. DOI: 10.3390/educsci12040243

[30] Skatova A, Ferguson E. Why do different people choose different university degrees? Motivation and the choice of degree. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1244. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01244

[31] Tadesse D, Weldemariam S, Hagos H, Sema A, Girma M. Midwifery as a Future Career: Determinants of Motivation Among Prep Students in Harar, Eastern Ethiopia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:1037-44. DOI: 10.2147/AMEP.S275880

[32] Taylor R, Macduff C, Stephen A. A national study of selection processes for student nurses and midwives. Nurse Educ Today. 2014 Aug;34(8):1155-60. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.04.024

[33] Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007 Dec;19(6):349-57. DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

[34] United Nations Population Fund; International Confederation of Midwives; World Health Organization. The state of the world's midwifery 2021. New York: United Nations Population Fund; 2021.

[35] Vermeulen J, Luyben A, O'Connell R, Gillen P, Escuriet R, Fleming V. Failure or progress?: The current state of the professionalisation of midwifery in Europe. Eur J Midwifery. 2019;3:22. DOI: 10.18332/ejm/115038

[36] Wilkes L, Cowin L, Johnson M. The reasons students choose to undertake a nursing degree. Collegian. 2015;22(3):259-65. DOI: 10.1016/j.colegn.2014.01.003

[37] Williams J. Why women choose midwifery: a narrative analysis of motivations and understandings in a group of first-year student midwives. Evid Based Midwifery. 2006;4(2):46-52.

[38] World Health Organization. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

[39] Zamanzadeh V, Ghahramanian A, Valizadeh L, Bagheriyeh F, Lynagh M. A scoping review of admission criteria and selection methods in nursing education. BMC Nurs. 2020 Dec;19(1):121. DOI: 10.1186/s12912-020-00510-1

Attachments

| Attachment 1 | Interview guide (Attachment1_zhwi000032.pdf, application/pdf, 89.84 KBytes) |