[Evaluation von Meditron3-70B für die medizinische Kodierung: Derzeitige Einschränkungen und Perspektiven für eine Integration in die klinische Praxis]

Coralie Galland-Decker 1Muaziza Usenbacher 1

Christophe Nunes 1

François Bouche 1

Giorgia Carra 2,3

Noémie Boillat-Blanco 3

Mary-Anne Hartley 4

Alexandre Sallinen 4

Jean Louis Raisaro 2

François Bastardot 1

1 Medical informatics, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland

2 Biomedical Data Science Center, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland

3 Infectious Diseases Service, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland

4 Laboratory for Intelligent Global Health and Humanitarian Response Technologies (LiGHT), EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland

Zusammenfassung

Das Aufkommen von Large Language Models (LLMs) stellt eine Herausforderung für deren Integration in die klinische Praxis, insbesondere für die medizinische Kodierung, dar. Diese Studie evaluierte die Leistung von Meditron3-70B, einem aktuellen Open-Source-LLM für den medizinischen Bereich, bei der Erzeugung von SNOMED CT- und ICD-10-Codes anhand von 200 fiktiven Konsultationsvignetten aus der Notaufnahme. Experten aus der Medizin bewerteten die Genauigkeit der Ergebnisse. Obwohl Meditron bei Standard-Benchmarks wie MedQA gute Ergebnisse erzielte, wurden erhebliche Mängel hinsichtlich der Relevanz und Vollständigkeit der erzeugten Diagnosecodes festgestellt, wobei nur 2% der Antworten als akzeptabel eingeschätzt wurden. LLMs sind zwar vielversprechend für die Unterstützung der klinischen Entscheidungsfindung, ihre derzeitige Fähigkeit, genaue und umfassende medizinische Codes zu erstellen, ist jedoch noch begrenzt. Die Integration spezialisierter Retrieval-Tools durch hybride Ansätze könnte die Kodierungsgenauigkeit verbessern und rechtfertigt weitere Untersuchungen in realen klinischen Umgebungen.

Schlüsselwörter

Large Language Models, Notaufnahme, klinische Kodierung, SNOMED CT, ICD-10

Introduction

Medical coding involves converting clinical information from electronic health records (EHRs) – often unstructured free text – into standardized codes according to established classification systems. This process is crucial for administrative and public health purposes, such as statistical reporting, reimbursement, and epidemiological surveillance [1]. However, it imposes a significant documentary burden on health providers, thereby contributing to professional fatigue and dissatisfaction. Meditron3-70B [2] is a large language model (LLM) specifically fine-tuned on various biomedical and clinical datasets, aiming to support various healthcare-related natural language processing tasks.

Our study investigates a central research question: How well does Meditron3-70B perform in real-world medical coding tasks in SNOMED CT [3] and ICD-10 [4], based on emergency department (ED) anamnesis? We focus on its ability to assign specific, accurate codes aligned with current classification standards.

Methodology

This study was conducted at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) between September and December 2024. We generated 200 fictitious clinical vignettes reflecting common presenting complaints in the emergency department. Each vignette simulated a pre-admission scenario, and the model was prompted to assign specific SNOMED CT and ICD-10 codes, per upcoming requirements for administrative coding of entry diagnoses used to determine reimbursement categories and care package allocations in the Swiss outpatient system. The outputs were evaluated by two physicians and three nurses (from internal medicine, pediatrics, psychiatry, and emergency medicine) using a 9-item evaluation grid based on a 5-point Likert scale.

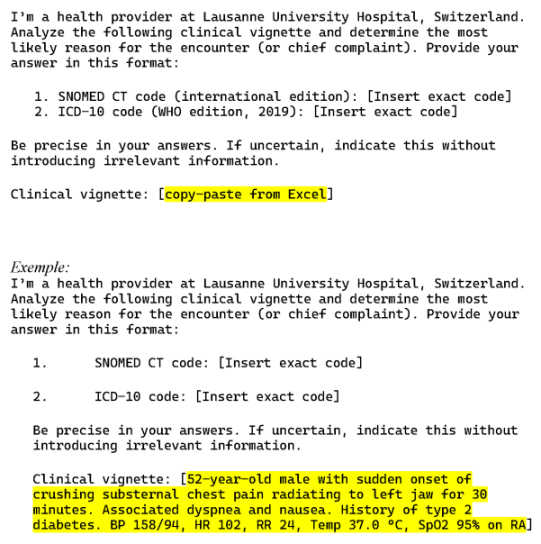

To elicit the model’s output, a standardized prompt was used (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]).

Results

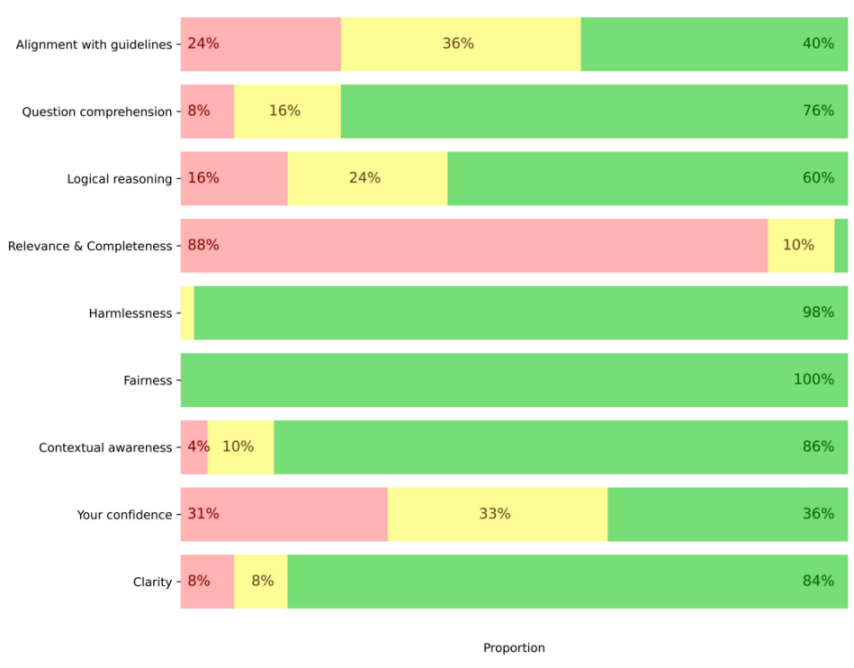

The evaluation of the model’s performance in identifying SNOMED CT and ICD-10 codes revealed heterogeneous results across the assessment criteria (Figure 2 [Fig. 2]).

Figure 2: Evaluation criteria: Unsatisfactory in red (1–2 points on the Likert scale), satisfactory in yellow (3 points), and highly satisfactory in green (4–5 points)

The model demonstrated significant shortcomings in the relevance and completeness of its responses, with only 2% rated as acceptable (4–5 points on the Likert scale). Confidence in the model was moderate, with only 19% of responses considered satisfactory (4–5 points). In contrast, the model performed well in question understanding (76%) and contextual awareness (86%). Finally, it achieved excellent results regarding fairness (100%) and absence of harm (98%).

Discussion

Our results show that the model struggles to produce relevant and complete diagnostic codes based solely on patient anamnesis despite a good general understanding of the clinical questions and context. Medical coding is a complex task that requires surface-level comprehension, nuanced clinical reasoning and the ability to synthesize information. The limited quality of the generated codes explains the moderate confidence reported by healthcare professionals, and highlights a key barrier integrating LLMs in real-world coding workflows.

These findings are consistent with recent studies, which also report that current LLMs (e.g. ChatGPT-4.5), often fall short in tasks requiring high precision and domain-specific reasoning [5]. While prompt engineering can help clarify expectations, it does not sufficiently compensate for the model’s limited access to up-to-date medical knowledge. Hybrid approaches such as Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), which enable dynamic access to curated external sources during inference, appear particularly promising [6], [7], [8]. They could help improve the specificity and accuracy of generated codes and better align model outputs with clinical documentation requirements.

Systematic comparisons with general-purpose models such as ChatGPT are needed to better characterize the strengths and limitations of specialized versus broadly trained language models. This study also highlights ethical and legal concerns inherent to generative AI in clinical settings. These include transparency of model outputs, accountability for errors or omissions, data privacy, and bias mitigation.

Conclusion

Meditron3-70B showed apparent limitations in generating relevant and comprehensive diagnostic codes from emergency department anamnesis alone. These shortcomings, consistent with other recent findings, suggest that current LLMs are not yet reliable for standalone use in complex medical coding tasks. Future research should focus on hybrid systems that combine LLMs with structured retrieval tools to enhance performance and increase trust in AI-assisted documentation within clinical settings.

Notes

Authors’ ORCIDs

- Coralie Galland-Decker: 0000-0001-8897-8473

- Giorgia Carra: 0000-0001-8002-224X

- Noémie Boillat-Blanco: 0000-0002-2490-8174

- Mary-Anne Hartley: 0000-0002-8826-3870

- Alexandre Sallinen: 0009-0005-1776-8539

- Jean-Louis Raisaro: 0000-0003-2052-6133

- François Bastardot: 0000-0003-4060-0353

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Dong H, Falis M, Whiteley W, Alex B, Matterson J, Ji S, Chen J, Wu H. Automated clinical coding: what, why, and where we are? NPJ Digit Med. 2022 Oct;5(1):159. DOI: 10.1038/s41746-022-00705-7[2] Chen Z, Cano AH, Romanou A, Bonnet A, Matoba K, Salvi F, Pagliardini M, Fan S, Köpf A, Mohtashami A, Sallinen A, Sakhaeirad A, Swamy V, Krawczuk I, Bayazit D, Marmet A, Montariol S, Hartley MA, Jaggi M, Antoine Bosselut A. MEDITRON-70B: Scaling Medical Pretraining for Large Language Models [Preprint]. arXiv. 2023 Nov 27. DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2311.16079

[3] SNOMED Intenational. SNOMED-CT. International Edition.

[4] World Health Organisation. ICD-10. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision. WHO; 2019.

[5] Soroush A, Glicksberg BS, Zimlichman E, Barash Y, Freeman R, Charney AW, Nadkarni GN, Klang E. Large Language Models Are Poor Medical Coders – Benchmarking of Medical Code Querying. NEJM AI. 2024;1(5):AIdbp2300040. DOI: 10.1056/AIdbp2300040

[6] Ng KKY, Matsuba I, Zhang PC. RAG in Health Care: A Novel Framework for Improving Communication and Decision-Making by Addressing LLM Limitations. NEJM AI. 2025;2(1):AIra2400380. DOI: 10.1056/AIra2400380

[7] Puts S, Zegers CML, Dekker A, Bermejo I. Developing an ICD-10 Coding Assistant: Pilot Study Using RoBERTa and GPT-4 for Term Extraction and Description-Based Code Selection. JMIR Form Res. 2025 Feb;9:e60095. DOI: 10.2196/60095

[8] Kwan K. Large language models are good medical coders, if provided with tools [Preprint]. arXiv. 2024 Jul 6. DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2407.12849